The geeky act of making lists of favourite books is a pleasure I don't think we should deny ourselves. What better way to get a snap-shot of someone's reading tastes and pick up on recommendations for great books you might have missed over the year. I read 112 books this year, many of them newly published in 2016 and many of them highly enjoyable. However, these ten books all show great craft but also feel personally significant to me. Click on the titles below to read my full reviews of each book. You can also watch my BookTube video talking about these ten books: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o7x_TPKvl7I&t=71s

The Man Without a Shadow by Joyce Carol Oates

Anyone who knows how Oates is my favourite author might think it is an obvious choice for me to put a new novel by her on my list, but this is truly an excellent book. The more I think about it the more layers it yields about the meaning of personality and romance. An unusual love story between a man with short term memory loss and scientist Margot that explores the elusive mechanics of the mind.

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

I can't ignore the significance of this novel coming out in an American election year when a campaign fuelled by racism and anti-immigration helped a politically-inexperienced misogynist enter The White House. This story about an escaped slave named Cora who travels a physical underground railroad to arrive in different states of racism America says something so significant about the times we live in.

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing

The state of loneliness is a curious psychological phenomenon which seems natural to the human condition, but one which is only increasing in an age of so-called online connectedness. Laing's incredibly personal and well-researched non-fiction book looks at the lives and work of many great queer artists to see how loneliness manifests in different ways. This is an incredibly touching and moving book.

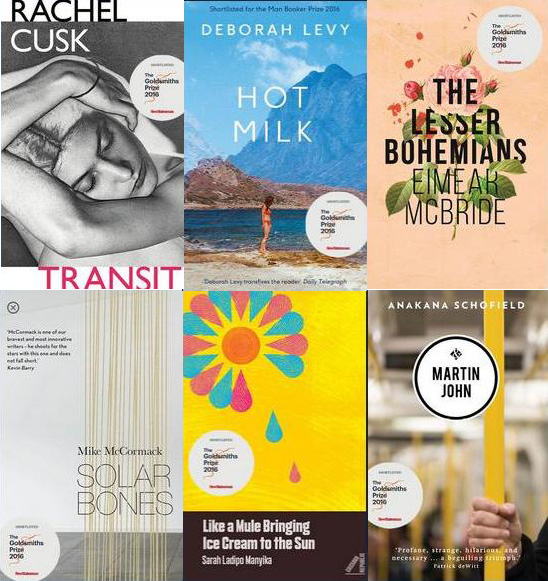

Solar Bones by Mike McCormack

Although it may seem daunting to read a novel that is one continuous sentence it comes to seem quite a natural thing as you enter the consciousness of its Irish protagonist. It's a significant reflection of the times we live in as much as it is as a moving story of family and the working life. Reading it is an electrifying experience.

Under the Udala Trees by Chinelo Okparanta

Great survival stories are both thrilling and heartening. This is a tale of a girl who survives a brutal civil war only to discover that her natural desire to love women goes against the religious beliefs of her family and community. She faces a very different kind of challenge to survive as she's pressured to settle down into marriage with a man and gradually assert what she really wants in life. It's a brutally honest and inspiring story which suggests strategies for unifying disparate communities which are bitterly embattled.

Dinosaurs on Other Planets by Danielle McLaughlin

Creating finely constructed short stories that give the impact of a full-length novel is a difficult challenge. But this is something McLaughlin accomplishes consistently and beautifully in this memorable and significant debut collection. Even though I read it at the very beginning of the year many of these stories about people across all levels of Irish society have remained clear in my mind. You can watch me discussing this and other great books of short stories from 2016 here.

The Gustav Sonata by Rose Tremain

Tremain's tremendous artistry for plucking an uncommon story from history and making it come alive is unparalleled. Here she writes about two boys in Switzerland in the time immediately following WWII, but moves backwards and then forwards in time to show the repercussions of political neutrality and hidden love. This is a beautifully accomplished novel.

Autumn by Ali Smith

There's no writer more daring and inventive than Ali Smith. Not only has she bravely planned a quartet of novels based around the seasons, but she's reflecting in them what's happening in society now. This novel focuses on the country's mood in the aftermath of the 2016 Brexit vote and an uncommon friendship between young Elisabeth and a mysterious old man Daniel. In doing so she addresses the meaning of nationality, the state of the modern world and the nature of language. She does this with great flair, humour and passion.

Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien

Music has played a large part in many great novels this year – from Rose Tremain's novel to Julian Barnes' most recent novel “The Noise of Time” - but Thien skilfully shows how the art of composition and the compositions themselves fare under fifty years of living under the Maoist government. A girl follows her family's history in this complex, absorbing story which culminates in a depiction of the infamous student protests in Tiananmen Square. It's an epic novel.

The Tidal Zone by Sarah Moss

It's always an immense pleasure to discover an incredibly talented author I've not read before and one of this year's great finds for me is Sarah Moss. This novel takes a potential family tragedy and expands the story to explore the messiness of ordinary life in such a tender and poignant way. It also reflects back to the past to consider the meaning of loss using such a disarming style of narration which totally gripped me.

Have you read any of my choices? Which are you most interested to read? Let me know some of your favourite books of the year. I'm always eager to hear about books I might have missed reading.