Ali Smith is an author whose writing embodies absolute passion, invention and positivity – this is true despite her new novel “Autumn” beginning with the line “It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times.” Because she is writing about the contemporary including this year’s recent significant referendum where the UK voted to leave theEuropean Union, this statement playing upon Dickens’ famous opening accurately reflects the political and social feeling for many people in this country. What Smith does in this novel is give a sense of perspective on this mood of all-encompassing gloom. She shows how while times might feel dire right now, it is simply a season in the turning of time. It’s the story of a young woman named Elisabeth Demand and her friendship with Daniel Gluck, an elderly man who lived through the rise of fascism in Europe in the 1930s. Together they debate ideas and create stories while witnessing the monumental changes happening in the society around them. Their exchanges are very different from the present popular mode of communication “which is a time of people saying stuff to each other and none of it actually ever becoming dialogue.” “Autumn” emphasizes the importance of art and literature as a means of communicating when dialogue between different factions of society comes to an end. In this way, this novel naturally follows on from Smith’s “Public Library”, a collection of wonderful short stories interspersed with real accounts of the personal and social importance of libraries and books for connecting people.

Another aspect of Smith’s positivity is the way in which her stories often involve charismatic and intelligent young people. Many like to moan about the coming generation by claiming they are aimless and lazy, but Smith frequently shows a real optimism and respect for her adolescent characters who are relentlessly inquisitive and creatively engage with the world. This novel moves backwards and forwards in time, recalling the occasions in Elisabeth’s youth when she first got to know her neighbour Daniel. Her mother Wendy is sceptical about this friendship, worries Daniel might have some ulterior motives and speculates that he is gay. Elisabeth astutely observes in response to this that “if he is… then he's not just gay. He's not just one thing or another. Nobody is. Not even you.” This is a continuation of an idea brilliantly realized in Smith’s last novel “How to Be Both” where characters weren’t necessarily one thing or another. In the imaginative and funny stories Elisabeth creates with Daniel they play upon this assertion showing the ever-changing and fluid nature of people, societies, language and the environment around them.

In opposition to the playfulness of this dialogue between the pair are the institutions which seek to hem in and pigeonhole people. In the present day Elisabeth tries to get a passport application put through the post office, but she’s told on multiple occasions after waiting in a long numbered queue that her photos and the head on her shoulders doesn’t meet required specifications. These scenes make a funny critique of the way our society frequently puts people through tedious regimented processes instead of giving individual attention. But it also takes a worrying look at the notion of citizenship during a time when who you are and where you came from will come under scrutiny as our government dictates who does and does not belong in our country. Furthermore, these scenes highlight how policies focused on classification and exclusion trickle down into the public consciousness causing factions and divisions within communities.

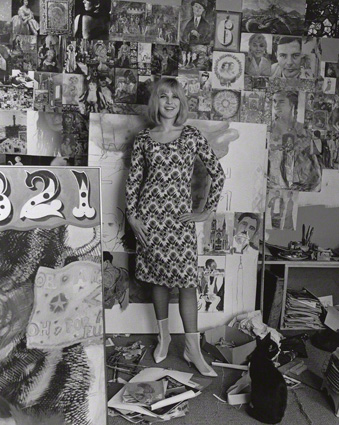

Pauline Boty

Elisabeth becomes fascinated by the little-known artist Pauline Boty who was Britain’s only female painter working in the Pop art movement of the late 1950s. As someone who studied Pop art in college and had a passionate interest in Andy Warhol, I feel ashamed not to have known about this artist before reading “Autumn”. Boty challenged conventional notions of representation and gender in both her art and life. She tragically died of cancer before she was thirty, but would no doubt have been better remembered and left a more substantial legacy had she lived and continued with her imaginative work. Through viewing her art work and studying her life, Elisabeth finds a way to engage with the creative ideas Boty set forth and applies them to how she questions and views the present time. In one memorable scene it leads her walking; she follows fields of cow parsley to land designated as private and encounters a man who tries to stop her using regimental language. This causes a disruptive crisis between the individual and the natural world.

One of the funniest parts of this frequently playful/funny novel is a section where Daniel and Elisabeth discuss a story about someone who disguises himself as a tree and becomes embroiled in a battle. Smith has written in the past about people’s connections to trees or transformation into trees. There’s a great tradition of metamorphosis in literature – everything from Homer’s “The Odyssey” to “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” – both of which this novel makes sly references to throughout. As well as being an entertaining and lively exchange between the two characters this mutually-created tale says something very moving about people’s connection to nature. It also highlights the connection between language and books, the way our words are inscribed upon paper and how there isn’t a separation between our ideas and the world around us. Also, their story which at first seems humorously abstract turns very personal for Daniel in a moving way. Smith is a master at catching the reader off guard with passages that are deeply emotional.

Smith plans for “Autumn” to be the first in a quartet of novels all named after the seasons. It’ll be fascinating to see how the books play out together and how much more we’ll discover about Daniel’s troubled past. At the start of the novel he washes up on a shore in a way that is reminiscent of Shakespeare's "The Tempest". I suspect Smith has more to say about the parallels between the changes happening in society now and what Daniel witnessed growing up. He makes a beautiful statement in this novel when he tells Elisabeth “always try to welcome people into the home of your story.” This is a hopeful cry for inclusivity and diversity against the current political movement towards shutting down borders. It’s a plea to really see all the people around us and acknowledge that they are part of our lives and our communities rather than shutting them out or pretending they don’t exist. “Autumn” triumphantly shows how our stories don’t belong to us alone but are part of a larger narrative of humanity and the time we live in.

Read an interview I conducted with Ali about "Autumn": https://www.penguin.co.uk/articles/in-conversation/interviews/2016/oct/ali-smith-on-autumn/