Something about reading my first novel by Mishima now at the age of 36 makes me think I would have appreciated him more if I read him in my early 20s. His writing is without a doubt very sophisticated and eloquent, but there is something about the philosophical digressions he goes on which feel much like an ardent university student making fanciful speeches where he’s trying to sound impressive. There are a lot of interesting points and it’s very well crafted, but I don’t think this is a book that flows as gracefully as a novel that is merely showing you what life is made of. I hasten to add that there is a meaningful story here amidst the sometimes fervent tangents. It’s basically a novel about three characters. Noboru is a precocious 13 year-old who discovers a hidden spy-hole into his mother’s bedroom. His mother Fusako is a widow with a successful business with some high profile clients who takes on a sailor lover. This sailor is Ryuji, a solitary man with a strict code of values who breaks from his life at sea after embarking on this affair with Fusako. The novel switches focus between these characters and tells a tale about sexual discovery, aging and becoming disillusioned with idealized notions about life.

Noboru’s complex adolescent state is described beautifully. He’s locked in his bedroom each night by his mother. His discovery of a hole between his bedroom and his mother’s gives him a way to extract revenge on Fusako by invading her privacy. It also yields contemplative thoughts on identity as Fuasako looks at herself in a mirror when she thinks she’s alone. Noboru has a burgeoning understanding of a new kind of world as he witnesses his mother’s love affair with the sailor whom he looked up to when he first met him. Apart from notions about a kind of Oedipus complex that this suggests, it forces Noboru to contemplate his epistemological position on life. Noboru longs to sail on ships himself but he “found himself in the strange predicament all sailors share: essentially he belonged neither to the land nor to the sea. Possibly a man who hates the land should dwell on shore forever. Alienation and the long voyages at sea will compel him once again to dream of it, torment him with the absurdity of longing for something that he loathes.” When presented with a solitary/exploratory life or a domesticated/fixed life, he surmises that the preferable option is the liminal space between the two. Isn’t this typical - for young men particularly? Both Ryuji and Noboru want to have it both ways: the security of having a home and the freedom to pursue limitless other possibilities.

Ryuji finds himself at a challenging cross-road in his life. He’s prided himself at working hard on his own, separate from the other sailors on his ship and building up substantial savings by not spending his money on frivolous things. However, he does spend money to lose his virginity with a prostitute in one scene where he hilariously images the thick mast of a ship while having sex with her. This suggests latent homosexual impulses which I can’t help reading into the story considering Mishima’s own homosexuality. But this isn’t something the author pursues because he remarks somewhat dismissively that “His sexual desires too, the more so because they were physical, he apprehended as pure abstraction; lusts which time had relegated to memory remained only as glistening essences, like salt crystallized at the surface of a compound.” I’m guessing the question of whether sexual desire is driven more towards men or women is too specific to fit into the grander statements about life that Mishima wants to make in this novel. Because Ryuji reflects that “I’ve never done much, but I’ve lived my whole life thinking of myself as the only real man” he sees himself separate from the human race or as a kind of embodiment of pure existence. The real challenge comes when he finds he wants to change course and that now “The things he had rejected were now rejecting him.”

It’s interesting the path Fusako’s journey takes, but she doesn’t feel as well developed as the boy and man. I was struck by a hilarious observation by Yoriko, one of Fusako’s famous female clients, where she considers “A prerequisite of any marriage… was an investigation by a private detective agency.” Rather than this spying presenting a complication in the relationship it’s affirmed as a great idea and carried out in a way that leaves everyone satisfied. This is a curious plot point which feels like it could have yielded a different kind of dramatic story, but it doesn’t go down that route. Overall, it seemed to me that the course of the story leaves Fusako behind. Although she’s a successful independent business woman she doesn't develop as a character. She simply comes to represent an anchor for Ryuji’s unmoored existence.

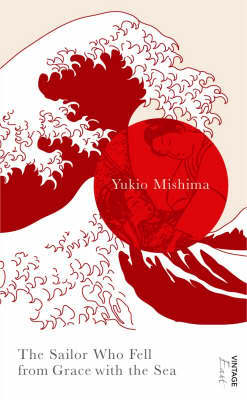

One of the most fascinating things about this novel is the adolescent gang that Noboru hangs out with. They are like something out of a Donna Tartt novel waxing philosophically about the sacred way life should be lived and methods for dangerously putting the world right when irregularities occur. They take the story down a dramatic path. Their actions inspire notions about the cyclical savage nature of life and how earnest passions can be ultimately squandered. I’m sure many of the subtler symbolic meanings of this novel were lost on me. I did enjoy the story and many of the thought-provoking statements the author makes. In the future I intend to read more of Mishima's work - especially with the beautiful red & white covers that Vintage came out with for all his novels. I was entertained and engaged by this novel, but not totally swept away by Mishima’s sea-faring notions about existence.