Zadie Smith's new book “The Fraud” is many things. It's a historical novel primarily set in 19th century London and Jamaica; it's a courtroom drama; it's about an unusual love triangle; it's about the ambition of novelists with some delicious appearances by Charles Dickens who makes bad jokes; it's about the end of slavery in Jamaica; and it's about what happens to truth when viewed through the lens of politics, the media, public debate and the craft of fiction. The story concerns a now semi-obscure historical novelist William Harrison Ainsworth (some of his titles outsold Dickens at the time) and The Tichborne Case, a famous trial that ran from the 1860s to the 1870s concerning a man who claimed to be a missing heir. Though this legal battle captivated the public at the time it's also now nearly forgotten. Between the author and the trial there is this novel's central character Eliza, a widow who is in some ways financially dependent upon Ainsworth. She is his housekeeper and reader. She's an abolitionist who forms a bond with Andrew Bogle, a man born into slavery who is one of the trial's key witnesses. Also, Eliza is fond of a long walk during which she observes Victorian London in tantalizing detail.

Eliza is a shrewd observer sitting in on discussions amongst prominent literary circles and watching the statements made in the courtroom by men whose demeanour often says more than their words. In this way we get a sly view beyond the surface of these interactions and the male dominated society surrounding her. However, as the novel progresses Eliza becomes a figure of intrigue herself. Between her intimate bond with William's deceased first wife Frances, a one-time intimacy with William himself and her late husband's illegitimate family, we get flashes of the truth Eliza either can't or won't openly accept. As the novel moves backwards and forwards in time we follow her journey towards acknowledging the reality of her personal life as well as the larger politics of her society. However, it's challenging to do this when there is so much unconscious misunderstanding and wilful deception surrounding her. She observes how “We mistake each other. Our whole social arrangement a series of mistakes and compromises. Shorthand for a mystery too large to be seen.” With so much confusion concerning what's true about other people's lives, acting in an ethical way can be extremely difficult.

In part, the novel is about how fiction comes to eclipse reality and how public consensus can eclipse truth. William writes historical novels which are based more in his imagination and stereotypes than facts. In this way readers come to know figures from the past through his distortion of the truth. Equally, “The Claimant” at the centre of The Tichborne Case achieves a large following that believes and partly funds his legal defence. Their faith in his claim is partly supported by Andrew Bogle's staunch conviction that “the Claimant” is the heir who went missing at sea. But how can Andrew's understanding of the truth be comprehended without knowing his own backstory or the legacy of slavery that was part of the British colonial empire? Eliza becomes the lynchpin towards seeing through the sensationalism of the case – partly because she has empathy enough to try to get to know Andrew himself. As his fascinating backstory is divulged, Smith shows the more complex personal realities at play within the more prominent public debates.

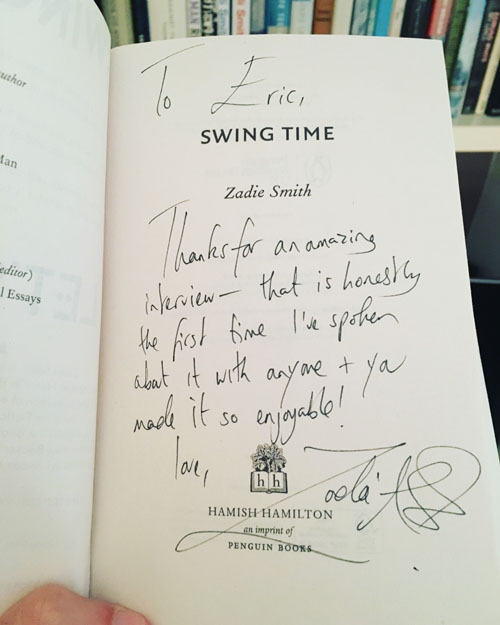

I had the pleasure of interviewing Smith about her new novel at a pre-publication event.

It's intriguing how this is a historical novel which seems to be critiquing historical novels themselves, the profession of writing and literary circles in general. At the beginning of one chapter, Eliza hilariously reflects: “God preserve me from novel-writing, thought Mrs Touchet, God preserve me from that tragic indulgence, that useless vanity, that blindness!” She sees how William's ambition to write removed him from being more fully involved with his family life (his first wife and his daughters) and his romanticisation of historical events distorts many people's understanding of history. Sitting in on their literary salons she's also privy to the pretensions and backstabbing which occurs amongst authors. In particular, Dickens is shown in quite a critical light. Smith seems highly attentive to the shortcomings of her profession and colleagues while also attempting to show in this novel what the best kind of fiction can do: expand readers' empathy and broaden their point of view to see the larger complexity of things. It's a tricky tightrope to walk and, for the most part, she gets the right balance.

Though Eliza is a highly sympathetic character who exhibits a lot of goodness, by the end of the novel it's shown she has her own shortcomings and areas of blindness. I enjoyed the way the story even gives a rounded view of such side characters as Sarah (the second Mrs Ainsworth) and Henry (Andrew Bogle's son). Their lives are fully fleshed out in many different scenes with witty dialogue and sharp observations. However, the structure of the novel is perhaps a bit too ambitious as it covers a lot of ground over a long period of time. It comes to feel a little unwieldy as the reader is continuously pulled into the past while the narrative also tries to delineate the complex events of the present. However, overall the story contains many moments of pleasure and it's a tale which leaves the reader with a lot to ponder. Like all the best historical fiction, it sparks a curiosity to want to read and understand more about some forgotten corners of the past.