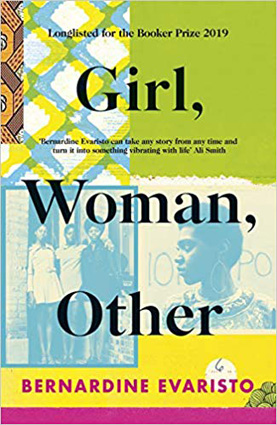

It was such a thrill to be at the award ceremony on the historic night of Bernardine Evaristo's Booker Prize win for her novel “Girl, Woman, Other”. At the time I was a great admirer of the book and was aware of her reputation, but I had no idea how many years of hard graft and dedication the author had devoted to reaching this point. Now, reading her memoir “Manifesto”, I also have such an admiration for this creative individual who has fused her experience and imagination to produce a body of literary works which artistically reflect the breadth of our culture and celebrate individuality in all its wondrous forms.

In concise sections Evaristo lays out how she got to this point by describing her diverse family background, the places she's lived, the relationships she's had, the community and politics she's engaged in, the development of her distinct form of fiction, the writers and figures who've inspired her and the ambition to persist as a creative person. She describes her experience with such charm, wit and wisdom it's extremely enjoyable to read. Evaristo wholly embraced the platform which winning the Booker Prize gave her and I've been in awe seeing how busy she has been chairing this year's Women's Prize, speaking on panels, providing endorsements for books and curating the 'Black Britain, Writing Back' series which included the excellent novel “Bernard and the Cloth Monkey” which I read earlier this year. This memoir is subtitled 'On Never Giving Up' and the book is really a wonderful testament to how the creative individual must persist and express themselves no matter what hardships are encountered.

While Evaristo poignantly describes her fluid sexuality engaging in affairs with men and women, one of the most arresting things about her story is learning about the abusive relationship or “torture affair” she had with a woman she calls “The Mental Dominatrix”. Here she found herself in a dynamic where she was mentally and physically abused in a way which sapped her creativity and spirit. Not only does this testify to how we can become trapped in such a destructive dynamic, but it sheds new light on the section of “Girl, Woman, Other” concerning the character of Dominique who was in a very similar situation. Knowing now that Evaristo was writing from experience makes this part of her novel all the more heartrending.

I also greatly appreciated her many pithy observations about how aspects such as gender, race, nationality as well as sexuality all play a part in who we are and how we exist in society but don't define us. In an ideal world these things wouldn't even need to be defined but because of the various imbalances and prejudices which persist they still play an important role. For instance, she describes how “Men and women live in the same world, but we experience it so differently.” It means that fiction and art play such an important role in expanding our point of view to really see how other people see the world. I admire the dedicated way which Evaristo has persisted in doing so over her life no matter the peaks and pitfalls of her profession as a writer and how she will continue to reflect the world back at us in exciting new ways.