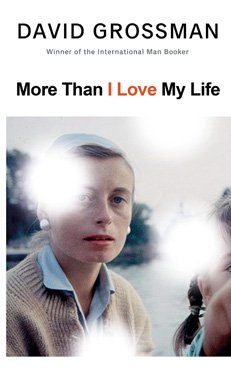

The older I get the more I contemplate what I can never know about past generations of my family. Even as I've tried to outline the facts and piece together story fragments, I know that there won't ever be a way to truly understand what my ancestors went through or why they made certain decisions. This is a subject Maria Stepanova rigorously contemplated as she sifted through family mementoes and records in her fascinating and extensive book “In Memory of Memory”. One of her conclusions seemed to be that whatever narrative we construct about the past doesn't necessarily give us any substantial insight or meaning. Equally, David Grossman rigorously questions the intention and value of documentation when it comes to examining family history in his compelling and moving puzzle box of a novel “More Than I Love My Life”.

The book opens with a narrator recounting the story of her parents and grandparents' lives on a kibbutz in the 1960s. It doesn't occur to this narrator to introduce herself as Gili until we're deep into the complicated relationships of her immediate family. She's enthralled with their stories (even though they occurred long before she was born) and they give the sense of having been told and retold so many times they've developed into a personal mythology. After the death of her grandfather Tuvia's first wife he married a Yugoslavian immigrant named Vera. Tuvia's son Rafael also falls for Vera's daughter Nina, but it's an unequal love affair as Nina is hampered by the violent circumstances of WWII and life under President Tito. Gili feels a deep anger towards her mostly-absent mother Nina as she's led a promiscuous life full of wanderlust. However, Gili is also aware that Nina's problems stem from something which happened when she was a girl – an unaddressed betrayal by Nina's mother Vera.

The second half of the novel takes place in 2008 when Gili and her father Rafael decide to record a documentary about Vera who has just turned 90 years old. Nina has returned for her mother's birthday and also reveals she's suffering from an illness which will cause her to prematurely lose her memory. In order to memorialise Vera's life and create an account which Nina's future self can use as a reference point, this family of four embark on a journey back to Vera's homeland as she recounts the horrors she endured during wartime. Many secrets and revelations emerge which lead to emotional confrontations. All the while, Gili and Rafael endeavour to film and interview Vera to better understand her life. It becomes clear that no matter how rigorously or honestly they try to document her account they won't ever fully understand what she lived through or why she made choices which put both herself and Nina at risk. Interestingly, in some sections the narrative slips to Vera's intensely gruelling imprisonment at Goli Otok, a barren island known as the “Croatian Alcatraz” that was used as a political prison when Croatia was part of Yugoslavia. In their earnest attempt at preserving Vera's memories and forming a reconciliation, they are left with more questions than answers.

I greatly appreciated how this complex and entrancing story explores issues to do with family, self-worth, the past and truth. The way it dramatises its characters yearning for understanding and a sense of belonging made me deeply feel for them. Though some scenes that occur in the present felt needlessly melodramatic I still got caught up in the intense feelings involved. This novel painfully shows that love doesn't necessarily allow for justice – especially when under the intensely pressurised circumstances of national upheaval when life is lived “on the edge of a knife”.