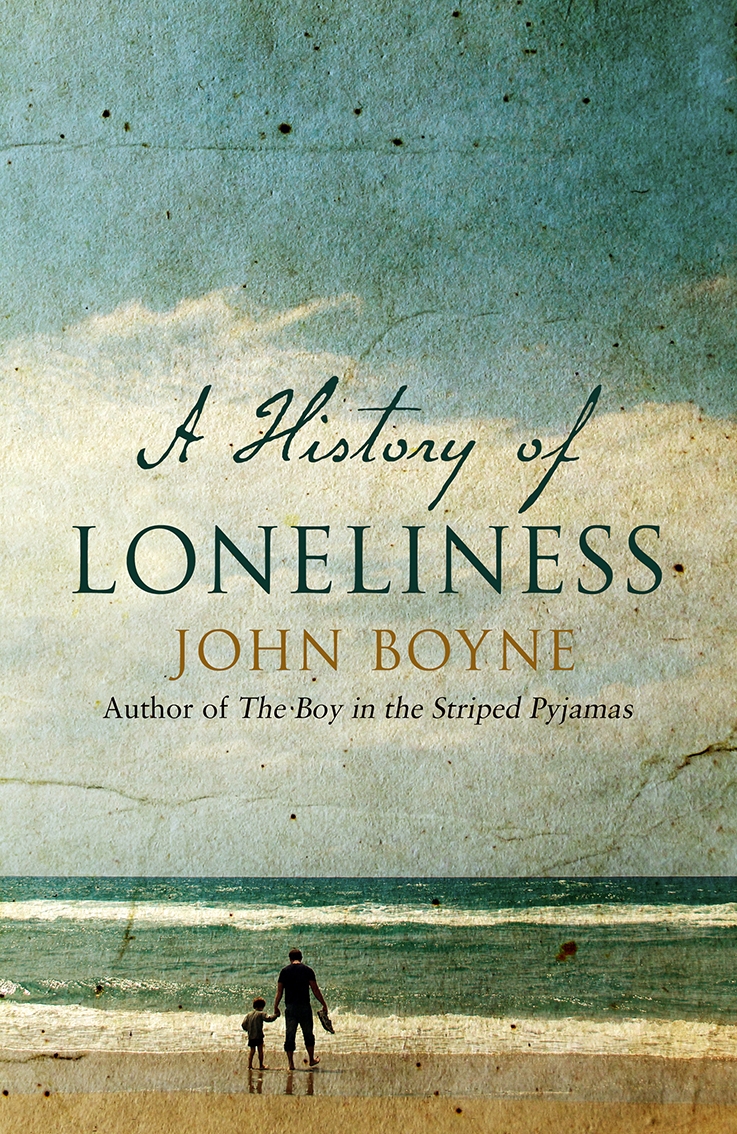

Having read Boyne's heartrending novel “A History of Loneliness” a little over two years ago, I was extremely keen to read this new novel which is certainly his most ambitious publication thus far. At over six hundred pages “The Heart's Invisible Furies” follows the life of Cyril Avery from his dramatic birth in 1945 to 2015. It's a novel that's truly epic in scope as it incorporates significant moments in history from the 1966 IRA bombing of Nelson's Pillar in Dublin to the recent referendum to permit same-sex marriage in Ireland. Boyne captures climatic shifts in societal attitudes over this seventy year period. For those who experience Irish life from day to day and suffer terribly from the constrictive ideologies of its domineering institutions, it feels as if nothing will ever change. As one character puts it: “Ireland is a backward hole of a country run by vicious, evil-minded, sadistic priests and government so in thrall to the collar that it’s practically led around on a leash.” However, surveying the societal shifts over a full lifetime through Cyril's point of view, the reader is able to see how things do slowly change with time especially through brave individuals who make themselves heard.

The novel begins in 1945 when the local priest discovers that Cyril's sixteen year-old unmarried mother Catherine Goggin is pregnant. He publicly denounces her, physically throws her out of the church and orders her to leave their small farming town in West Cork. Inexperienced and nearly penniless, she bravely makes her way to Dublin where she decides to give Cyril up for adoption after giving birth to him. Cyril is raised in the home of Charles and Maude Avery who are two very different, charismatic and highly original characters. Charles is a wealthy and powerful businessman with many vices including gambling, womanizing and alcoholism. Maude is an irascible reclusive chain-smoking writer who produces a new novel every few years and delights in how few copies get sold “for she considered popularity in the bookshops to be vulgar.” In a hilariously memorable scene recounting her only public appearance, she reads her entire novel to the audience without stopping until everyone leaves the bookshop in exhaustion. Although these characters are an absolute delight to read about, they make frightful parents treating Cyril more as a lodger than a son and continuously reminding him that he's “not really an Avery.”

Each section of the novel leaps forward seven years showing Cyril’s development and struggles throughout his entire life. It’s speculated that our lives dramatically change in seven year periods of time. The philosopher and mystic Rudolf Steiner hypothesized that there are significant changes in human development in seven year cycles that are linked to the astrological chart. Scientists say that every cell in the human body is replaced every seven years meaning that biologically we become completely new human beings. One of the most touching things about “The Heart's Invisible Furies” and why it justifies its length is how it shows how orphaned Cyril is not limited to one set path in existence, but has multiple opportunities to grow and change over the course of his life. Sometimes he makes poor decisions and other times he realizes his full potential over these seven year strides. The priest who banished Catherine and her child borne out of wedlock condemned them to a life of shame and misery. Although they both periodically suffer throughout their lives, they survive and flourish. Their story is a great testament to how the human spirit overcomes the narrow-minded dictates of society.

Through Cyril’s perspective the novel gives a personal view of some the most horrific social and historic events in his lifetime including fatal homophobic beatings, a teenager kidnapped and mutilated by IRA members, concentration camp survivors, the sex trade in Amsterdam, the stigma of AIDS and its early epidemic in NYC and the September 11th attacks. These subjects are treated seriously and sensitively portrayed. However, the novel is nowhere as bleak as this list makes it sound. It’s often a very comic story with vibrant scenes and memorably idiosyncratic characters. Boyne uses a satirical wit and Dickensian social eye when writing about characters such as Mr Denby-Denby, a flamboyant civil servant, or Mary-Margaret Muffet, a conservative uptight Catholic girl, or Miss Anna Ambrosia who gets monthly visits from her “Auntie Jemima” and dismisses Edna O’Brien’s books as “pure filth.” These characters brilliantly reflect the social attitudes of their respective time periods and show up their ludicrous ingrained systems of belief. It’s moving how many characters reappear periodically throughout the years and Boyne shows how they either change or obstinately stick with their provincial points of view.

One of the most important aspects of the novel is Cyril’s homosexuality and the severe difficulty of growing up as a gay man in Ireland during his lifetime. Cyril develops an early love and lust for his boyhood friend Julian. But where heterosexual Julian can be flagrantly sexual and voracious in his female conquests, Cyril’s sexual experience is confined to cruising and he’s constantly terrified he’ll be found out. He feels an “overwhelming, insatiable and uncontrollable lust, a yearning that was as intense as my need for food and water but that, unlike those basic human needs, was always countered by the fear of discovery.” It forces him to make dishonest choices and romantically engage with women when he really longs for a relationship with a man. One of the greatest obstacles his character must overcome is learning to be honest about who he is, especially to people who will appreciate and value him regardless of his natural desires. Other gay characters in the novel have diverse ways of either concealing or expressing their homosexuality: “Ireland, a country where a homosexual, like a student priest, could easily hide their preferences by disguising them beneath the murky robes of a committed Catholic.”

Nelson's Pillar after the 1966 IRA bombing

Even as some gay characters begin to live quite openly in later years, Cyril struggles to freely express himself or confide in people he should trust. It’s touching how the long-lasting deleterious effects of being made to feel like an outcast or deviant in society manifest in the ways the characters relate to each other or shut each other out. It produces an overwhelming sense of isolation, something that Cyril recognizes when he encounters another character late in the novel: “It's as if she understood completely the condition of loneliness and how it undermines us all, forcing us to make choices that we know are wrong for us.” This movingly describes the way people who’ve been ostracised by society can hurt themselves and others. Yet, there are moments when characters can form a unique unity and bond over their estrangement when it’s acknowledged that “We're none of us normal. Not in this fucking country.”

The title of the novel comes from an observation that theorist Hannah Arendt made about W.H. Auden “that life had manifested the heart's invisible furies on his face.” It’s an apt way of describing this novel which is an intense, poignant and vivid account of a man’s hidden conflicts. His personal development fascinatingly coincides with that of his country. What’s especially impressive is the artful way that Boyne conveys an awareness of other characters’ inner struggles only through their action and dialogue. It makes for a convincing portrayal of a diverse social landscape with lots of dramatic and gripping scenes. It’s a breathtaking and memorable experience following Cyril’s expansive journey.