Recently I made a video talking about examples of contemporary authors who fictionally reimagine the lives of classic authors. But it's been a funny coincidence that the past two novels I've read do this exact thing in creatively pioneering ways. Cristina Rivera Garza brought back multiple versions of the Mexican writer Amparo Davila in her gender-bending “The Iliac Crest” and now Olivia Laing has done so in her first novel “Crudo” by merging her own identity with that of punk poet and cutting-edge novelist Kathy Acker (who died in 1997.) I've been anticipating this novel so much because Laing's nonfiction book “The Lonely City” was such an important touchstone for me in understanding the condition of loneliness. “Crudo” follows a re-imagined Kathy twenty years after her death in 2017 during the languorous Italian days in the lead up to her marriage to a much older writer. She reflects on the state of the world from dispiriting politics to her interactions with groups of artists to the challenging interplay between the inner and outer world. In doing so Laing forms a fascinating portrait of the modern crisis of an individual who feels she has opportunities and access to vast amounts of information, but is in some ways powerless to enact change or escape her own privilege.

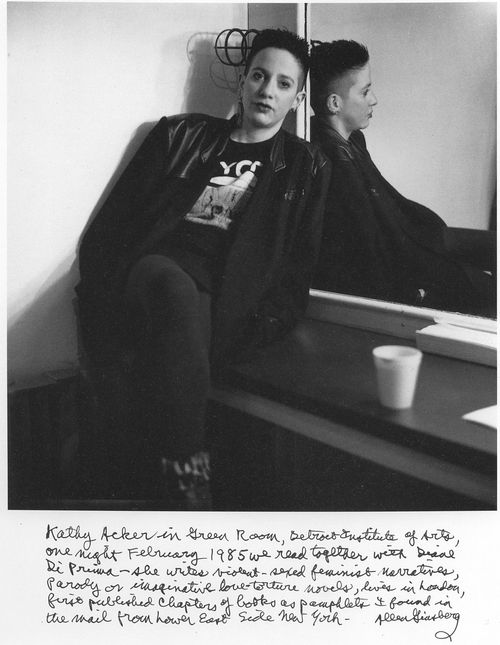

Part of what makes Laing's nonfiction so mesmerising is the intense connection she describes with the artists and subjects whose lives she explores so sympathetically. These are often figures who were marginalized but whose creations and activism pushed the conversation forward. So it's unsurprising that she'd be drawn to the figure of Kathy Acker whose anti-establishment aesthetic incorporated styles of pastiche and a cut-up technique to explore elements from her own life as well as subjects such as power, sex and violence. Acker's fiction also appropriated a number of prominent classic authors such as Arthur Rimbaud, Emily Bronte, Marquis de Sade, Charles Dickens and Georges Bataille. It's described in this novel how “She wrote fiction, sure, but she populated it with the already extant, the pre-packaged and readymade. She was in many ways Warhol’s daughter, niece at least, a grave-robber, a bandit, happy to snatch what she needed but was also morally invested in the cause: that there was no need to invent”. In the same way, Laing transposes lines from Acker's writing (as well as some other authors) to form a modern narrative which is in some ways autobiographical. This literally bleeds Acker's thoughts and ideas into Laing's sensibility to reiterate what has been said before and say something new.

I'm really fascinated by writing techniques which incorporate pre-existing texts such as Jeremy Gavron's recent “Felix Culpa” which forms a compelling self-contained fictional narrative. But “Crudo” is much more intensely personal describing its protagonist Kathy's desire to break out of the bounds her gender and her time period: the bleak summer of 2017 when the public dialogue was overwhelmed with talk of Brexit and Trump (as it still is.) It describes how she both wants to engage in this conversation and escape from it in the transformative space of solitude “It was just she kept sneezing, it was just that she needed seven hours weeks months years a day totally alone, trawling the bottom of the ocean, it’s why she spent so much time on the Internet” and how our online lives filtered through mediums such as Twitter allow us immediate access to information, but also have a curious distancing effect. This leads to a understandably pessimistic view of the world with its diminishing resources and reactionary politics:“It was all done, it was over, there wasn’t any hope.” But, of course, Kathy as an individual persists as does the propensity to create art that engages with and reacts to this fraught world.

Part of me felt uncertain at first if Laing's method of invoking the figure of Kathy Acker was necessary for her to fictionally express a state of being that is evidently so painfully real for the author herself. After spending a lot of time thinking about what this novel says, I'm convinced that Laing's method isn't just a formal experiment but a necessary act. For all its desperate searching and relatable despair, “Crudo” is a surprisingly romantic novel in the way Laing breathes new life into a pioneering writer from the past and pays tribute to the power of committed love for comfort and solace. One of the most powerful scenes comes when Kathy is at a dinner party where it describes her grappling to eat a crab. She pounds on it persistently to crack inside and there's a moment where her personality melds with that of the crustacean: “Someone was pounding on the door. The hammer, smashing the crab’s back. She wanted to be cracked open, that was the thing, only on her own terms and within preordained limits. There were rules, she changed them.” This beautifully encapsulates the core of this narrative which feels encroaching forces threatening our liberty and our bodies, but which shows a determination to change the landscape which is so rapidly transforming beneath our feet. “Crudo” is both a beautiful drag act and an urgent cry to witness, remember, connect and move forward.