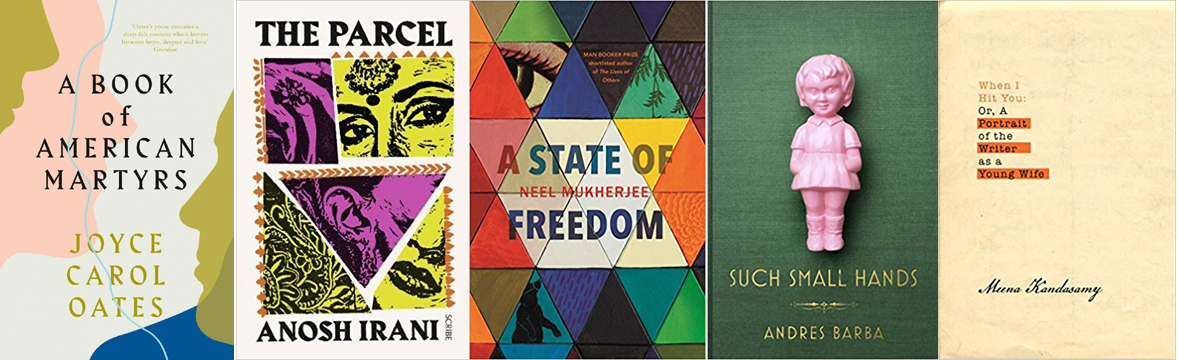

Every once in a while a new book will remind me how novels are really lawless. Of course, the very word novel means that every iteration of this form of storytelling makes its own rules. But some fiction like the jubilantly inventive books of Ali Smith or the wide experimental canvass of Joyce Carol Oates audaciously twist structures we’ve become accustomed to, subvert genres and play with language to produce exciting results. I was thrilled to find George Saunders’ first novel “Lincoln in the Bardo” accomplishes this as well. I’ve read some of his stories in the past, but this novel confirms for me that his high level of literary esteem is entirely warranted. He takes a melodramatic subject like Abraham Lincoln visiting his son’s grave and makes it profoundly emotional. He embraces clichés about the afterlife to create uproariously funny or terrifying scenes of possession, haunting and the judgement day. He picks out quotes from period documents and nonfiction, but interjects his own history between the lines. He writes dialogue as if this were a play to form a chorus of witnesses to the incredibly intimate scene of a father saying goodbye to his deceased boy. In short, he grabs the historical novel and flips it on its head.

Although their son Willie is suffering terribly from a case of typhoid, the Lincolns can’t cancel a grand party being thrown at the White House. During the night the stricken boy passes away and is put to rest in a graveyard – except his spirit doesn’t rest. He now exists in the realm of the Bardo which is a Tibetan word that means an intermediate state where the soul is still connected to earthly attachments before it can pass onto another life. Here the laws of nature are broken for the stricken spirits who dwell there so their physical characteristics are muddled with the strident emotions they experienced towards the ends of their lives. The two main spirit protagonists are deformed so that Hans Vollman is lumbered with a horrendous oversized erection from the marriage he never consummated with his young bride and the features of Roger Bevins III are crowded with a multiple ears, mouths and noses after his botched suicide. Along with the troubled spirit of The Reverend Everly Thomas, these beings seek to guide the young spirit of Willie in his afterlife.

There are a profusion of aberrations in appearance and behaviour for the many other beings that crowd this graveyard. Most especially, some spirits are locked in perpetual battles that have carried on into the afterlife such as a demonic couple with unholy cravings, a professor and pickle producer stuck in an endless circle of mutual adoration and a white supremacist that is endlessly beaten by the black man he demeans. In a nightmarish way, this portrait of the unsettled hereafter depicts our conflicts of class, race, romance and sexuality trapped in a painful circle. It's like endless episodes of those trashy sensational talk shows, but written in a way which is surreal and brilliantly insightful. There is a beyond which these spirits cannot move onto because they can’t let go of their attachment to these irresolvable struggles. The heartrending conflict at the centre of this book is the fight for the boy Willie’s soul between the spirits who want to usher him on to the next realm and the father who cannot let him go.

There have been other novels which have intelligently played out the psychological and social conflicts of existence in a version of the afterlife. Most notably, Hilary Mantel’s “Beyond Black” depicts a medium plagued by her own demons and Will Self’s “How the Dead Live” depicts a woman who died of cancer guided through the guilt-laden landscape of the hereafter. However, the book that most came to mind when reading Saunders’ novel was the ‘Nighttown’ or ‘Circle’ episode in James Joyce’s “Ulysses”. Not only is this also written like a play script, but it becomes a hallucinatory experience as the fears and passions of the protagonist are externalized. Similarly, in Saunders’ distorted physical plane traditional linear notions of time collapse and the ravenous ego runs riot. The ensuing chaotic drama is a physical realization of the unchained dark side of consciousness where every private part of being takes shape before our eyes. It’s an experience that is both liberating and utterly terrifying.