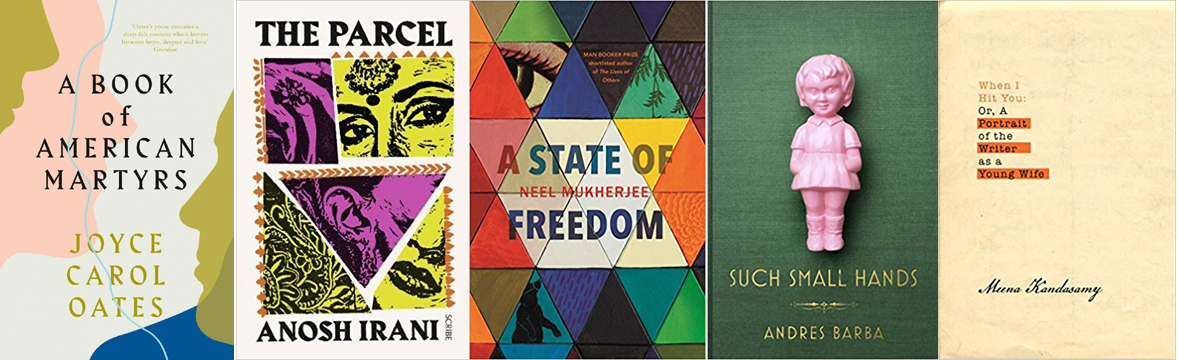

As adults we can recall flashes of feeling and indulgent fantasies that we experienced as children, but these are inevitably wrapped in a kind of silk-smooth nostalgia. Even memories of intense anger and pain are altered by the distance of time because this past now has a context. When you’re child there is no context. So much of literature tries to simulate the actual feeling of childhood, but only manages a sentimental simulation. But something in Andrés Barba’s narrative gets it so exactly, eerily right that it’s as if (as Edmund White pronounces in his afterword to this novella) “Barba has returned us to the nightmare of childhood.” Reading the story of seven year old Marina and the children in the orphanage she’s taken to after her parents’ death made me feel all the chaotic roiling emotion and imagination of my youth again. “Such Small Hands” is an extraordinary experience and it’s so artfully done that I’m in awe of its brilliant construction.

Apparently this story is partly inspired by an incident in Brazil that occurred in the 1960s where a child in an orphanage mutilated another child and was found playing with their body parts. This novella doesn’t indulge in the gore that this occurrence makes you imagine. But it definitely unsettles by inserting the reader into an alternating series of perspectives that makes you feel the precarious line children tread between reality and fantasy. In the first part we follow Marina in the immediate aftermath of her parents’ sudden deaths. She’s bluntly told what happened after their car accident, but it doesn’t stick to her reality because she can’t understand its full meaning. Barba has a startling way of showing how language and the words adults use when speaking to Marina don’t correlate to actual things in her mind. Even when she’s told she’s being taken to an orphanage this has no meaning for her because she has no idea what it is.

Even more extraordinary is the process Barba describes when Marina tries to make sense out of the world. She’s taken to see a psychologist and finds that she can’t adequately describe her experiences or produce the desired response: “Whenever her memory failed her, she’d just invent a color and slot it between true things. That seemed to change the scene, to turn her memories into things that were solid, things you could take out of your pocket and put on a table.” It’s a brilliant way of describing how we create stories out of our experiences and how we find our existence slotted within a narrative. No matter how earnestly we try to stick to facts and honesty, our memories are inevitably textured by the language that we turn them into. Once that experience has been cemented into the words within a story it’s forever altered and we’re left wondering, as it’s later stated in the novella, “How is it that a thing gets caught inside a name and then never comes out again?”