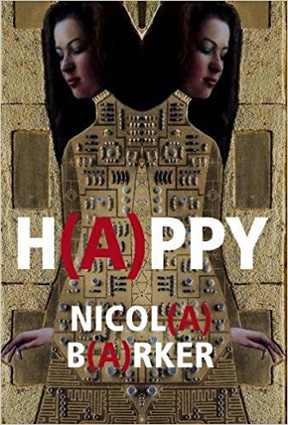

Nicola Barker’s novels consistently surprise and puzzle me with their wide-ranging subject matter, discursive style and wondrously mind-bending sensibility. She’s a writer frequently in tune with what’s happening now whether it’s memorialising a magician’s 2003 performance art in her novel “Clear” or investigating the contemporary cultural and ethnic landscape of England through the life of a boorish pro-golfer in her novel “The Yips.” So it feels like another creative feat that she sets her new novel “H(A)PPY” not just in a dystopian future, but in a post-post apocalyptic time. Here she charts the journey of a musician named Mira A as some inner rebellion forces her to question the meaning of freedom, creativity, individuality and, yes, happiness itself. The result is a fascinating tale which speaks strongly about our modern times and demonstrates impressively daring narrative ingenuity.

Far in the future after society has been ravaged by a number of disasters, the general population has been reigned into a state of consistent harmony by plugging their lives into a continuous stream and an overarching graph which monitors and stabilizes their lives. All basic needs are cared for with clothes that instantly fit to meet a wearer's needs. Sexual frustration isn't an issue because people's genitals have shrunk down to virtually nothing due to an evolutionary process. Unhappiness has been ironed out from the populace through something like that age-old Buddhist adage: ‘if one can eliminate desire/attachment, one can eliminate suffering.’ Any inconsistent or strong feelings are flagged in the narrative of this collective grid and Barker shows this by actually changing the colour of the text on the page. Words that might incite chaotic emotion such as arrogant or embarrassment are subject to a “pinkering” effect. This System corrects such inconsistencies in its population through chemicals or, in extreme cases, ominous-sounding clamps fitted around the head.

The modern parallels are immediately obvious in that (if you use social media) you are frequently contributing to and participating in a continuous collective narrative of text and images. While ostensibly this should be an arena for open/free-thinking debate, we must ask ourselves sometimes how much we both monitor each other and ourselves, modifying the language we use and what we post to fit in with each other or not be too disruptive. No one wants to be subject to an online backlash. Yet we participate because we want to participate just as Mira A wants to cleanse her narrative stream in order to be equanimous. She believes in the righteousness of what are called “the Young” who exist in a subdued present state of perpetual harmony. But an issue keeps arising where her affirmation of a H(A)PPY state persists in “disambiguating” and “parenthesising.”

Mira A has begun to form her own narrative in the text of this book and that's where the trouble arrises. This sets her existence in a timeline. If you are cognizant of the past and thinking about the future you are subject to the interplay between memory, imagination and the present time you live in. Here is the chaos of consciousness which is never stable, but always shifting and surprising and raising more questions. We try to make sense of the world when there is no sense to be made which is why some of us are obsessed with reading so much, but no matter how many books we read they will never be enough. Instead, we're perpetually considering other narratives and letting these mingle with, inform and colour our own. When Mira A finds herself unable to stop the flow of her narrative someone who challenges her observes “What is behind the blind alley? you scream. What is the mystery? What is the secret? 'But these are empty questions. There is no secret here, no mystery, just empty speculation.'” There is no definitive answer or ultimate knowledge, but we keep asking questions, reading about other lives and telling our own stories.

A performance by Agustin Barrios. In her preface, Barker suggests listening to his music while reading this novel.

Mira A finds herself embroiled in a struggle between someone who is trying to stabilize the System and someone who is trying to break it with a revolution called “The Banal.” No matter how ardently and frequently she chastises herselfwith the phrase *TERRIBLE DISCIPLINE* her narrative continues, her behaviour becomes increasingly erratic and random streams of information flood in. She's haunted by and seeks to riff off from the music of Agustín Barrios who was a Paraguayan virtuoso guitarist and composer from the early 20th century. Like a Google search which plunges us into a rabbit hole of infinite information his music leads to interjections about the colonial history of Paraguay, the suppression of its native language and social oppression. Add to this a haunting sense of Mira A's connection to a distant red planet, a bizarre twin self (Mira B), a brown-eyed girl in a photograph, a cathedral constructed out of phrases and a sinister mechanical canine named Tuck and the story gets very weird. About halfway through this novel it becomes totally wild where the text leaps off the page, changes font, inflates, overlaps, fizzles, twists backward and shades into different colours. Mira A even dips her finger into the text to form cryptic hieroglyphic shapes.

This is a novel that you either play along with or get turned off by. I enjoyed the crazy ride. If you are continuously fascinated by but overwhelmed and dispirited with the boundless streams of information to be found online (like I frequently am) Barker reflects this well. At the same time I was moved by the way the story evokes questions about the interplay between our stream of thoughts and our online social timelines. Consciously or not, we try to cultivate and control online personas by the information we choose to share or manipulate or withhold or erase. Mira A wants to simply fit in and be happy, but her personality has crooked edges. It's only through embracing our differences and contradictions that we're able to feel fully ourselves. Despite innately knowing this we keep trying to regulate ourselves and control the way people perceive us. That's what makes this fantastical novel feel so prescient and real.

Read a fun interview with Nicola Barker here: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jul/22/nicola-barker-books-interview-love-island-happy