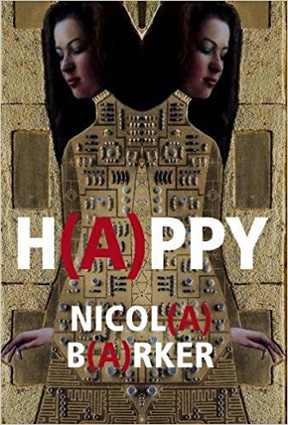

Lately it feels like Nicola Barker hasn’t been able to finish writing a novel without wanting to blow it up. Her last novel “H(A)PPY” was set in a future society where everyone’s mind was plugged into a single continuous stream and its hero’s consciousness became more hallucinatory while the text itself morphed into multi-coloured fragments and bizarre structures. It seems like there’s more tension in her narratives lately where the fourth wall is breaking down. Her new book “I Am Sovereign” is a self-designated novella. Within the story it’s stated “This is just a novella (approx.. 23,000 words)”. And its story is quite simple on the surface. The 49 year-old protagonist Charles creates customized stuffed bears and is seeking to sell his house in Wales. Over a twenty minute period estate agent Avigail presents the house to prospective buyer Wang Shu accompanied by her daughter Ying Yue who has come along as her translator. But the concept of this tale is merely a box within which Barker illuminates the artificiality of her characters and uses them as ciphers to discuss concepts of narrative itself. What little story there is soon breaks down – Barker even states at one point “Nothing of much note happens, really, does it?” Instead, Barker engages in arguments with particular characters and muses upon the nature of language, storytelling and authority. There’s a frenetic energy to Barker’s writing which is irresistible if you’re in a good humour or frustrating if you’re after an old-fashioned plot.

The thing about reading such a self-conscious and angst-ridden story is that it ought to be eye-rolling, but Barker has such clear affection for her characters that it feels like she really wants to grant them complete independence while also controlling them. “The Author can’t bear the idea of those four people leaving Charles’s tiny work room. They feel so alive to her.” Traits and details are assigned to characters but just as quickly they’re questioned because the characters believe differently. This complication comes most into play with the introduction of a character named Gyasi “Chance” Ebo who feels it’s an injustice that Barker has dragged him into her narrative. The character and author bicker and eventually his role in the story is replaced by that of another character. Barker toys with the limits of independence that characters can have to break free from an author’s designated plan and write their own story. This has obvious parallels to how we exist in society – especially in contemporary British society which is plagued with the question and democratically decided edict of Brexit. Are we creating the boundaries within which we want to exist or are those boundaries being written around us?

The characters are particularly inured to modern-day gurus found on YouTube who dole out advice. One such proponent advocates the goal “To be Sovereign. To be present, positive and boundaried.” There’s a resistance in Barker’s characters to be the screens she is projecting upon, but they are also aware there is no independence without their dependence upon her. It’s like the spiritual paradox of free will versus predestination. The comparison is very apt because Barker’s fiction is quite often consumed with questions of faith and spirituality. The characters in this novella are superstitious and seek revelation. However, the religious concerns expressed aren’t about indoctrination so much as they’re about searching and epistemological questions. Barker seems to take all this very seriously while also recognizing it’s absurd and her concerns are ultimately unanswerable. In her playfulness Barker is able to have it both ways in this novella. She states “shouldn’t fiction strive to echo life (where everything is constantly being challenged and contested)? Or is fiction merely a soothing balm, a soft breeze, a quiet confirmation, a temporary release? Why should it be either/or? Can’t fiction be exquisitely paradoxical?” I enjoyed the way this novella so joyously presents authorial problems and questions rather than a story with an affirmative arc. It’s like a teddy bear whose stuffing is oozing out, but you love it nevertheless.