As I wrote in a previous post, I was invited to be a shadow judge for this year’s Sunday Times/Peter Fraser & Dunlop Young Writer of the Year award alongside some other fantastic bloggers including Naomi from TheWritesofWomen. Given that the self-defined mission of her blog is to only cover books by women, I’m very proud to host Naomi’s reviews of the three shortlisted male authors on my blog and it’s interesting what different views she has compared to my own thoughts about the books. If you want to read my review of The Ecliptic click here.

Elspeth ‘Knell’ Conway, celebrated artist, is holed up in Portmantle, a retreat on a Turkish island. Directed to this mystery location by her sponsor, she befriends playwright MacKinney, novelist Quickman and architect Pettifer. Into their world arrives seventeen-year-old, Fullerton.

From our very first glimpse of him, we understood that he was one of us. He had the rapid footfalls of a fugitive, the grave hurriedness of a soldier who had seen a grenade drop somewhere in the track behind. We could recognise the ghosts that haunted him because they were the same ghosts we had carried through the gates ourselves and were still trying to excise.

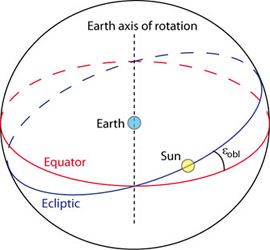

As the quartet keep watch over the troubled youngster, they also battle their own creative demons. Portmantle, Knell explains, exists out of time – as does art – as well as providing a sanctuary where artists can relocate their artistic desires. Each has a failed project which has driven them to the retreat. For Knell it’s a commission for which she was attempting to render The Ecliptic – ‘a great circle on the celestial sphere representing the sun’s apparent path among the stars during the year’ – on a mural for the Willard Observatory.

While the first and third sections of the novel take place at Portmantle, the second takes us back into Knell’s past documenting how she became an artist, her rise to prominence and her relationship with the artist Jim Culvers.

Elspeth’s from a Clydebank family and attends Glasgow School of Art on a scholarship – a detail far more plausible in the 1950s and ’60s of the novel than the present day. There she’s taught by Henry Holden who tells her to ‘Paint what you believe’. When the external assessor finds Elspeth’s blasphemous painting Deputation unworthy of a grade, the school denies her graduation and she goes off to London – thanks to Holden – to be Jim Culvers’ assistant. Holden says it’ll take a while for Culvers to realise she’s better than him. When that does happen, Culvers’ agent sets up Elspeth’s first show.

While at Portmantle, Knell comments on her name:

I always suspected my work was undermined by that label, Elspeth Conway. Did people exact their judgements upon me in galleries when they noticed my name? Did they see my gender on the wall, my nationality, my class, my type, and fail to connect with the truth of my paintings? It is impossible to know. I made my reputation as an artist with this label attached and it became the thing by which people defined and categorised me. I was a Scottish female painter, and thus I was recorded in the glossary of history.

While Knell sees an issue with her name and gender, Wood does something few male novelists do well in portraying her purely as an artist and a human. Knell reads precisely as a female painter because Wood never treats her as one. His focus is on the creative process and her relationships with fellow creatives.

The Ecliptic focuses on the creative process throughout the novel. At Portmantle, Knell and her friends worry that they have lost their abilities. They over analyse their work, attempting – and failing – to recreate past highs, or avoid artistic endeavour altogether. They work in secret, rarely discussing their progress, or lack of it. In the novel’s second – and strongest section – Elspeth learns her craft, encountering the disparity between the public’s, the critics’ and her own views of her work. Wood uses this section to consider the effect on an artist’s confidence and, therefore, their work when external forces begin to exert pressure on the creative process. It’s no surprise that Elspeth, still only twenty-six, struggles to cope.

In his attempt to explore how the creative process works, Wood pulls a sleight of hand on the reader which is revealed in the fourth and final section. At the Young Writer of the Year Award bloggers’ event, Wood said that he knew he was taking a risk with this. Whether or not he pulls it off will, I suspect, depend on the taste of each of the novel’s readers. For me, it was an ambitious – and an interesting – undertaking and I’d rather see a novelist challenge themselves to produce something unusual and difficult than play it safe. Whilst I wasn’t wholly convinced, the very end of the novel is inspired and very clever; it left me feeling that Benjamin Wood is one to watch, I suspect he’s going to produce something very special indeed.