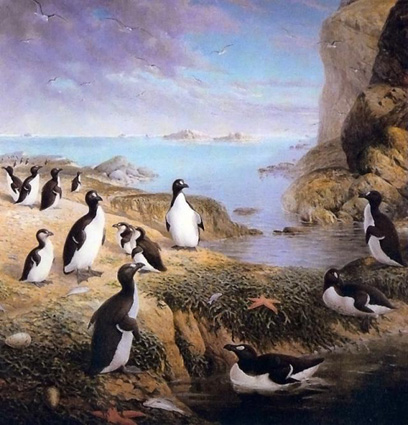

This is Jessie Greengrass’ debut book which won this year’s Edge Hill Short Story Prize. This is the only UK award that recognizes excellence in a published short story collection. There is something beautifully mesmerising about this author’s distinctive voice which is at once highly intelligent and deeply emotional. The characters in these twelve stories often find themselves at odds with the life they’ve ended up with producing feelings of estrangement and loneliness. The breadth of imagination used in creating these oftentimes surprising tales makes them utterly mesmerizing. They span great swaths of time and place from a sailor who hunts a group of birds on a remote rock to extinction to a dystopian future where the narrator is sequestered in an underground bunker to a smelly misogynist in the 1500s who witnesses a peculiar plague. Yet, there are also stories set in very recognizable and relatable situations such as a narrator stuck working in an impersonal call centre, a girl caught in the middle of her parents’ bitter separation and a lovesick student unable to focus on her thesis. The unashamedly long-titled “An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk, According to One Who Saw It” is a daring and diverse collection that makes a big impact!

Many characters in these stories desire impossible forms of escape from their present circumstances. For some this is filtered through a (very relatable) form of escapism by exploring alternate lives found online. In ‘All the Other Jobs’ the narrator wishes to take on enticing employment that will take her out of her present location or work that will engage her creatively such as becoming a lookout for polar bears in the arctic, a lighthouse keeper or an armourer for the Royal Opera House. Ironically the infinite possibilities she finds online induce stasis rather than any move towards making an actual change in her life. The same is true in 'Some Kind of Safety' where the narrator is trapped underground with a limited food supply but instead of usefully plotting a way out of this circumstance dreams instead of being able to go back online and look at cat videos.

The wish for escape is most emotionally realized in the story ‘On Time Travel’ where the young narrator whose father has died dreams of entering another version of reality by finding a time slip. This isn’t simply grief but also suffused with a kind of guilt because they hadn’t been a happy family so that “it seemed so awful that something so obviously terrible might in some ways come as a relief.” Thus the narrator and her mother find it painfully difficult to move on. The story ‘Scropton, Sudbury, Marchington, Uttoxeter’ is also laden with guilt about a failed relationship between a child and her parents. Making a life for herself far from her parents’ green grocer business, the narrator of this story returns many years later to the site of their business after her parents have died and the grocer stall has long been closed down. Here she lingers like the spectre narrator in Jean Rhys’ story ‘I Used to Live Here Once’ caught in an emotional stasis anchored in the past. She notes “it is strange how memory retains the structure of things and the details but so little in between.”

A character who does find freedom from his difficult life is the sailor in 'The Lonesome Trials of Knut the Whaler'. Shipwrecked and alone, Knut buries the body of the ship’s former captain at sea taking pride in the fact that he is now captain of the ship. The only trouble is that the ship is wrecked, the crew is gone and there is only a slim chance that he will survive living in or being rescued from this remote location. It seems that escape comes with a heavy price.

In the story ‘The Comfort of the Dead’ Greengrass posits that the intense desire to escape will mellow with time. As his life progresses and his wife leaves him, protagonist David finds that “In age, the fussy confines of his life began to seem appropriate: he no longer struggled between what he was and what he felt he ought to be.” Rather than change his circumstances, David remains in place with the ghosts of people he once knew increasingly visiting his bedside. Instead of pestering him to change like Ebenezer Scrooge’s ghosts they are an entirely benign presence who he finds comforting. However, this also feels tragic as all he has in his life are spectres rather than real people such as his wife with whom he found “the more he looked the more impossible it seemed that she should be his wife at all.” David would prefer the version of his wife that he imagines over the real woman and consequently ends up entirely alone.

Extinct Great Auks

The same is true of the narrator of ‘Three Thousand, Nine Hundred and Forty-Five Miles’ whose male lover leaves her because he’s uncertain about their relationship. Greengrass has a startlingly beautiful way of describing her feeling of loneliness and her desire for a physical/emotional connection with strangers she sees around her. She imagines how the man she loves finds a new partner and has a fulfilling new life. Yet, when he eventually returns, he can’t live up to the fantastically successful version of him that she’s created in her mind and no longer desires the real man before her. Such ironic twists and explorations about the tension between reality and the imagination are a great strength of Greengrass’ writing.

I felt deeply involved reading the skilfully written stories in “An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk, According to One Who Saw It” – not least of all by the solemn, meditative feeling that the stark and chilling title story left me with. These stories meaningfully explore the modern individual’s crisis of alienation and belonging through a creatively wide range of characters, locations and situations. It’ll be fascinating to see what Jessie Greengrass writes next.