“North Woods” started a little slow for me as Mason fleetingly presents his initial characters and mixes his styles of story telling. However, I quickly became aware that this novel centres around a single location from the moment of its birth with a foundation stone being set in the ground. Rather than introducing any character or group of characters who will lead us through the narrative, the book's focus is a yellow house in New England. As soon as I let go of the impulse to focus on any one individual's journey I could get into the flow of the story more. Of course, sections about later inhabitants are also longer so I naturally felt I knew them better and became really engaged by the story when I was introduced to a soldier/fruit enthusiast and his daughters.

As each section leaps forward through the decades there's a poignant accumulation of the stories of people who proceeded living in this abode. Traces of those who've previously inhabited the house remain. I like how Mason builds a layered sense of time. I've always found it touching to think about who might have lived in my house before me and who might live here when I eventually leave. There's a strange intimacy knowing we've shared this same physical space but will probably never know anything about each other's lives beyond changes made to the home's structure. Who knows what drama played out in this same space? That's what the author shows us tracing this line of inhabitants and I think it's very clever how this accumulates into a special poignancy.

The way Mason mixes songs, articles and maps into the narrative adds to this because this documentation tangibly shows the traces of those who've lived there before. I know for some it might feel jarring to be pulled out of the flow of the story by these but (for me at least) it adds another dimension to the novel and makes the North Woods feel like a real location imbued with so much history. I also enjoy how the author interjects some occasional humour such as a joke about a trick played on a thieving farmer family or a Minister's theory that the events of the Bible “had actually transpired in New England” with examples of potential parallels. These little asides are welcome since the story involves a lot of serious drama.

I must admit that the novel stirs sentimental feeling in me as well since I grew up in New England. The descriptions of the seasons and natural environment are very evocative. I appreciate the mention of specific things such as a regional flower called lady slippers and chickadee birds which I was very familiar with when I was young. At the same time larger American conflicts throughout different time periods seep into the experiences of people who pass through the same house. Mason evokes a strong sense of atmosphere though sometimes his description can lapse into cliché. In the first 40 pages I noticed he used the same adjectives: “violet consumes the lemon-yellow wings of the viburnum” and “She looked then much as she does now: a clean facade of lemon yellow”. This particular phrase always stands out to me because I heard a creative writing instructor once say it's better to describe something as “lemon yellow” rather than as “yellow” because it creates a stronger sensory experience for the reader. That's true but it's now become overused. However, that's a minor quibble in an otherwise beautifully written story.

As I continued to read this novel I felt a building anticipation to discover who might inhabit this location next. The form of narrative also continuously changes and I especially enjoyed a chapter composed of letters written from a painter to a poet. I'm a sucker for a tale written in epistolary form – especially one set in the distant past where you know the mail took a long time to reach its destination so there are interesting gaps and experiences which must have occurred between the correspondence. Again, to some readers, the changes in narrative might feel disruptive but I found it refreshing. It's also impressive that Mason can convincingly write in many different styles from true crime pulp to notes for a lecture intended for a historical society.

As much as I enjoyed the whole novel some sections would have felt melodramatic and over the top if I'd read them in isolation. At one point there's an outrageous séance which reaches a feverish gothic pitch. But I think because it's set in a single location and continues to involve previous inhabitants there is an added pleasure and meaning. I know some readers have been put off by supernatural elements in the story. To me this felt playful and I enjoyed the Beetlejuice vibe, but it also adds to this progressive layering of history which Mason builds.

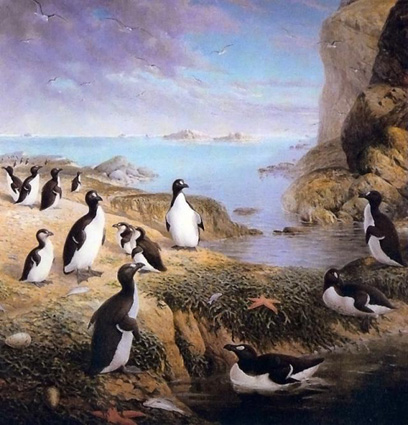

Equally, it's a book that kept me on my toes. The characters change from section to section so I had to reorientate myself in new stories, but also the author changes his style of storytelling and even moves into the consciousness of a beetle. This was very funny and unexpected. And it's also inventive how it's incorporated into the overall plot and changing natural landscape. The narrative seamlessly slides between the micro and macro in this way yet always revolves around this one house. I also appreciate how this is represented in the imagery set between sections as well. There's a map of marked trees in the area, but also the paths carved by the beetles. When viewed from this perspective such landscapes become both large and small. It's an artful way of referring to larger stories of people and the nation while selecting to focus on certain pieces.