It’s been quite a ride following the Man Booker Prize this year from the astounding quality of the novels on the long list to the heated race between the six books on the short list. When I first read “Lincoln in the Bardo” in March I was completely awestruck by this unique and powerful reading experience. So it threw me into such a quandary about whether this should win or Ali Smith’s wonderfully rambunctious and relevant “Autumn.” Of course, last year’s surprise winner “The Sellout” taught me how difficult it is to gauge what the judges might decide. So it felt equally plausible that this year’s winner could have been the accomplished novels “Exit West”, “History of Wolves” or “Elmet.” The oddball for me this year was Paul Auster’s “4321” which I’ve still not finished reading. There’s a lot to admire about it, but it seems overlong and the novel’s concept means that some of it feels quite repetitive. It must have been a really difficult decision picking a winner, but I’m glad Saunders' novel got the award. The chair of judges Lola, Baroness Young commented “The form and style of this utterly original novel, reveals a witty, intelligent, and deeply moving narrative.”

Special presentation editions made for the shortlisted authors

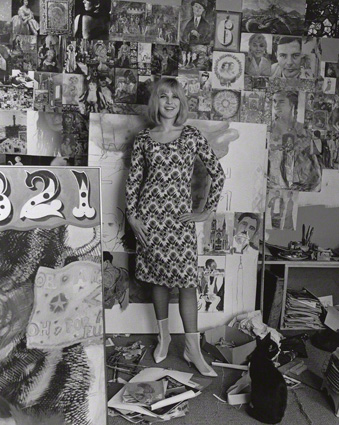

With Ali Smith at the Guildhall

I spotted Mohsin Hamid chatting with the Duchess of Cornwall

Last night I was lucky enough to be invited to the pre-reception drinks before the award announcement at the Guildhall. There was a beautiful display of special editions of all the shortlisted novels. These unique designs really capture the spirit of the books. I decided to root for Ali Smith to win especially after the powerful reading she gave at the Booker shortlist readings on Monday night. It literally brought tears to my eyes hearing her describe the mood of the country in her narrative. There were hundreds of people in the Royal Festival Hall audience and it struck me how accurately she had captured all the complex and contradictory feelings of the country and how everyone in that room recognized and related to her words. Ali has told me before that her spirit animal is a pink armadillo so I had a special t-shirt made with an illustration of this adorable creature surrounded by Autumn leaves. She was wonderfully calm and sincerely talked about how it doesn’t matter who wins since they are all such excellent novels. That certainly chimes with why I love a prize like the Booker because the real pleasure of it is debating the different qualities of several great novels. I also went to some of the publishers’ parties and right up to the announcement I was still discussing the books on the list with people, many of whom had a different favourite. The prize is also an opportunity for me to place a cheeky little bet which I did right after this year’s longlist was announced. I went with my instinct that George Saunders would win and it’s paid off!

I’m already looking forward to what new gems will come up on next year’s Man Booker International Prize as well as the main prize!