Intense curiosity has surrounded Australian author Gerald Murnane since a prominent New York Times Article from 2018 asked in its title ‘Is the Next Nobel Laureate in Literature Tending Bar in a Dusty Australian Town?’ The literary community adores having a genius spring from obscurity – especially one who has been working diligently and quietly producing books for years. The trouble is that not much of his writing has been available outside of Australia, but this year the wonderful publisher And Other Stories are bringing out a couple of his books.

So I picked up “Border Districts” to see why Teju Cole states that “Murnane, a genius, is a worthy heir to Beckett.” It turns out to be an apt characterization of this author because this novel is dominated by the voice of an old man living on the edge of civilization sifting through resonant images from his past and highlighting more of what he’s forgotten than what he remembers. Rather than plot we’re offered a way of seeing through the kaleidoscope of the narrator’s consciousness the ideas and sensations which persist in his mind - though their origin has frequently been lost.

Sometimes I ask myself what’s the good of reading as much as I do. Is it about the pleasure of the experience, my edification or connecting with high culture? Of course, it can be about all three. And, although I have the urge to read as much as I can, it creates a ridiculous anxiety that the more I read the more I’m apt to forget (hence one mission of this blog is to help aid my recall.) The narrator of this novel focuses frequently on the experience of reading and surmises that “whatever I had forgotten from my experiences as a reader of books had not deserved to be remembered.” This seems to discount one of the great joys of reading which is rereading where you can often discover things you missed the first time around or interpret what you’ve read very differently because you’ve aged and have more experience.

What’s really interesting about the narrator’s assertion is about the impressions which works of fiction leave rather than the exact arrangement of their words. “I have not yet forgotten the period in my life when I read book after book of fiction in the belief that I would learn thereby matters of much importance not to be learned from any other kind of book… I can recall many images that occurred to me and many moods that overcame me, but the words and sentences that were in front of my eyes when the images occurred or the moods arose – of those countless items I recall hardly any.” I like how this expresses the way we’re left with an overall feeling from a novel because, in a sense, we’ve lived through it. And, though the exact details or quotes they contain might be lost, our bodies and minds can recall the sensations of that experience.

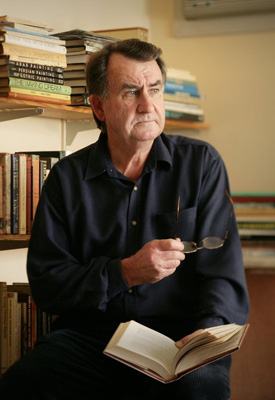

Gerald Murnane

Much of the story is preoccupied with the narrator trying to recover something he wrote down amidst all his accumulated possessions or trying to understand why certain memories dominate his thoughts. We get impressions of his early life being taught in a religious school and the outline of his family life, but the drama of the story resides solely in the narrator’s striving to connect his present sense of being with his past. There’s a tragicomedy to this endeavour which is very Beckett-like especially when he fruitlessly tries to write to a woman he heard on a radio broadcast. But the true beauty of his tale is how recurring imagery such as the experience of looking through stained glass or a coloured swirl within a marble takes on a profusion of meaning amidst his ruminations.

There’s something curiously refreshing about the staunchly technophobic perspective of the narrator and his endeavour to grasp the meaning of his past. Given how the internet provides us with quick access to so much information and prompts us to relentlessly document the minutiae of our daily experience, the narrator’s strategy for sitting at a remove from his familiar home and the people closest to him represents a valuable counter way of being. It shows how letting go can be more important than the act of memorializing because it sharpens the focus on who you really are. It also beautifully highlights how our lives may be nothing more than a muddle, but that doesn’t mean our experience isn’t meaningful.