“Elemental” is a sweeping historical novel that spans seventy years, multiple generations and two continents. But the story is primarily concentrated through the warmly-engaging and Scottish voice of Meggie Tulloch. It’s the early 1970s and, late in her life, Meggie realizes she has little time left so decides to write down the story of her early years for her granddaughter Laura. However, some things are difficult to tell, particularly family secrets that have been buried for many decades. But she feels it’s vitally important for her granddaughter to understand where she came from. She explains “The story of where you come from is real, as real as memory can ever be, and not so easy as fairytales.” Her tale shows the ways in which we inherit different aspects of our ancestors’ lives - not only their physical traits and characteristics of their personality but the hard battle for survival.

Tunnelling back through time Meggie reveals how she was once a red-headed hearty daughter of a rural traditional fishing family in the early 1900s. Her adolescent life is evoked with vivid detail so much that you can feel the tremendous claustrophobia of living in a small village governed by superstition with a tyrannical grandfather and sparse resources. Despite showing great intelligence and finding an early passion for books (including the poetry of Emily Dickinson), it was difficult for a girl at that time to find any independence or further education. So she becomes a herring girl and builds a life of her own through brutally hard labour and determination by working alongside groups of women who gutted the fish which were brought in by men who sailed the seas around the British Isles.

There is something so beautifully tender about the way Meggie reveals the past by writing in a familiar voice directly to her granddaughter who she affectionately calls “lambsie”. Emotion wells to the surface in the process of recounting a past of poverty, lost loved ones, first romance, wartime hardship and the nervous excitement of eventually setting off from Scotland for a new life in Australia. The directness of communication makes it all feel so present and real as if she’s speaking in front of you. Inevitably, she begins to muse upon the nature of memory itself. How random it can seem what remains and what doesn’t so that she thinks “how strange it is that sometimes we manage almost to erase the memory of pain to spare ourselves, and other times it’s as though we’ve taken to it with a polishing cloth.” It seems to me true how some hurt we’ve experienced in our lives is pushed away and forgotten while other pain still feels so immediate.

One of the most effective things about this novel is the way relationships are shown to change over time. Initially Meggie idolizes her older sister Kitty and eagerly follows in her footsteps living the life of a herring girl. But gradually the relationship changes as her sister encounters challenges and hardships. Equally, the initial tender love affair she has with her husband Magnus morphs into something so different in the many years that pass and after he’s drawn into war. She describes how “Each day it grew, the pile of things we could not say to each other because too much time had passed now.” It seems a sad fact of relationships – not just with lovers, but friends as well – that the longer things are left unsaid the greater the silence and distance grows between people. It makes Meggie’s magnanimous gesture of earnestly trying to communicate her life story to a granddaughter who she’s lost touch with all the more heart-warming.

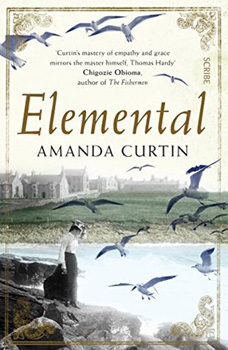

Herring girls of the early 20th century

Late in the novel, the narrative abruptly shifts from Meggie to her granddaughter Laura and Laura’s daughter-in-law. The stories of their immediate problems seem disorientating and confusing at first after spending so many pages in Meggie’s confident voice, but gradually their added stories take on greater significance which pushes the novel into new realms and draws the later generations back to Meggie’s beginnings.

Growing up in coastal Maine, a lot of the first paid work I did was at a seafood restaurant where I had to wade through piles of seafood, preparing it and burning my hands over fryer vats cooking it. Of course, my pain was nowhere close to the degree which Meggie suffered working as a herring girl. But, even though the location was different, I felt I could really visualize, smell and even taste the coastal life that Amanda Curtain so skilfully renders in believable detail. It feels like “Elemental” belongs in the tradition of great Victorian literature like Thomas Hardy. Yet there is something so refreshing in the voice and sensibility of the narrator which feels relevant and new even though she belongs to another century.