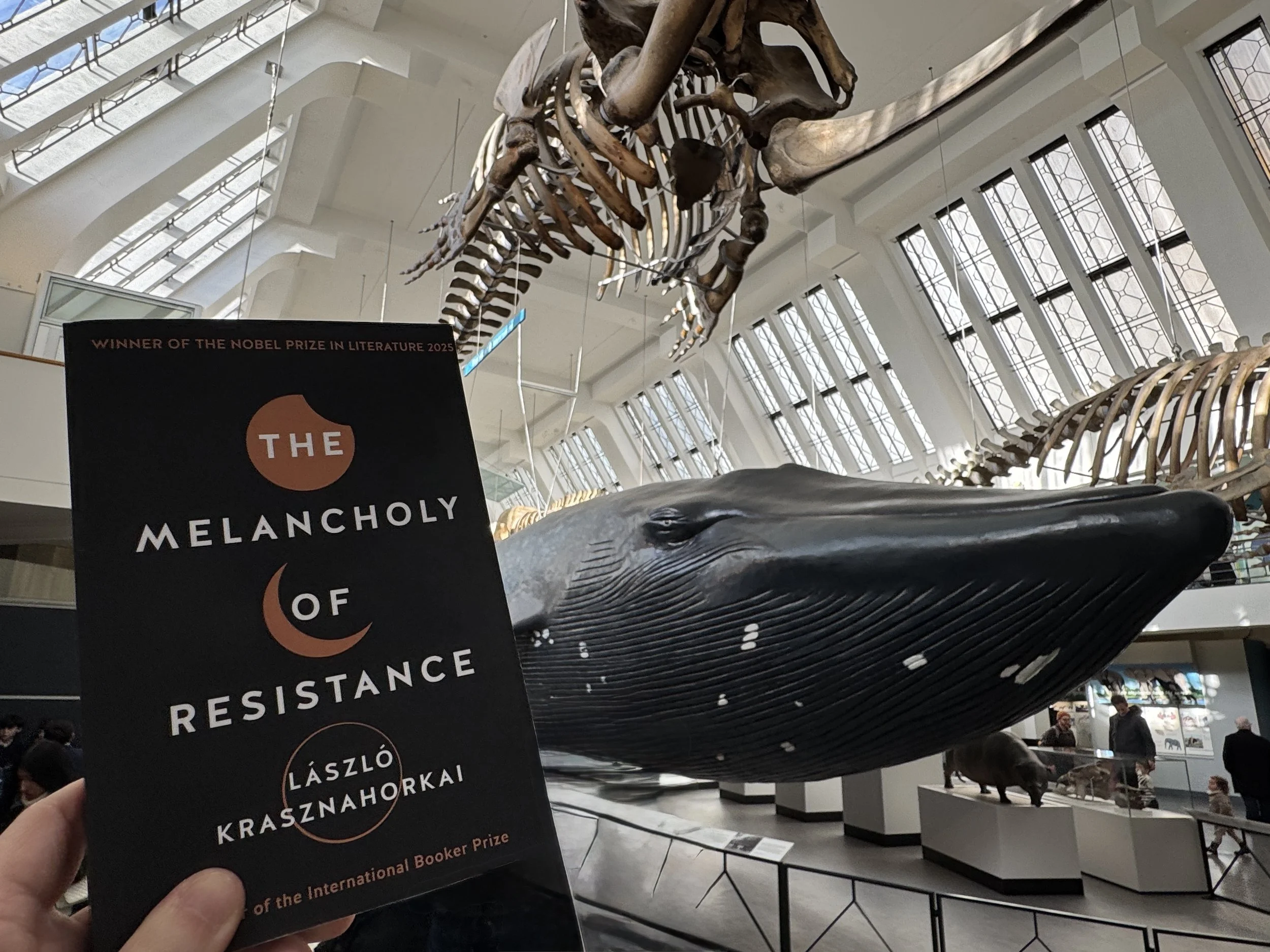

I'm always keen to try reading something from the most recent winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. This novel is a thoughtful exploration of a breakdown in society and the different philosophical positions people adopt to navigate through increasingly difficult circumstances. With its blocks of text, often confusing plot and unsettling atmosphere, this is most definitely a challenging read. But, given it was first published in the late 1980s, it also feels surprisingly relevant to disruptions we're seeing in the world today. It was written at a time when the author himself had witnessed the breakdown of communism in Hungary. There are parts of this book that are also filled with dark humour and a profound sense of wonder. I took a few hours to go to the Natural History Museum in London and spent time reading by a giant model of a whale to really add to the experience of this moody tale.

It took me a bit of time to get over the physical challenge of reading this novel. In order for my vision not to blur and keep my place I had to run my finger down the margins as I read. The run-on sentences and prose that flows like lava (as Szirtes has described it) requires a lot of attention and patience. It was difficult to know when I could take a break from the book and whenever I came to the end of a sentence at the start of a page it felt like I could finally exhale. I think the layout of this text is meant to reflect the sense of claustrophobia and overwhelming sense of doom felt by the citizens of this Hungarian town. I appreciate the effect the author is going for but personally I'm not convinced it's necessary. There are many instances where paragraph breaks could naturally be inserted and make the reading experience easier on a practical level. But, as it was, it certainly became a different kind of immersive experience and at times I felt hypnotised by the way it locked me into the details of these characters' increasing sense of dread and the chaos unfolding around them.

Though the format of the text was difficult, I was immediately compelled by the story as stuffy and snobbish Mrs Plauf has such an awful train ride being sexually pursued and struggles to make it home. I appreciated how we're gradually introduced to unsettling details occurring on the periphery giving a sense that things aren't quite right. I found the eeriest detail to be about the weather where it was freezing cold but it no longer snowed and the trees were uprooting as if the environment itself had died. The arrival of scheming Mrs Eszter brought a compelling dramatic element to the story though the full extent of her motives to acquire power and control only became clear to me as the novel went on. I did like the comically absurd scene in a bar as Janos assigned roles to the drunks to simulate planetary movements while the weary bartender waited for them to leave. However, as the narrative moved deeper into Janos Valuska and Gyorgy Eszter's stories it became increasingly unclear and hard to follow. I think this is intentional as the town descends into a state of lawlessness and all the characters were equally disorientated. But also these two central male characters had such strong idealistic values regarding the symmetry of the cosmos and the harmony found in a perfect piece of music that following their intense logic and philosophical positions was demanding.

I found the best way to read this novel was just to go with the flow and the overall atmosphere rather than getting bogged down in trying to understand the details of what was occurring. My favourite part was when Janos goes to see the stuffed whale from the travelling circus and the intense experience of being confronted with such an immense formerly-living creation. The writing here felt very beautiful and moving to me. It can be debated what the whale actually means or represents. Certainly there are religious, mythological and literary reference points for it. For me, it felt like an embodiment of how all life and every civilisation will eventually end no matter how enormous or seemingly indestructible.

Another striking element of the story was the Police Chief's two sons who start out as wannabe thugs when we're first introduced to them and then we meet them again later as crying children who have been completely overwhelmed by the chaos and abandoned by their drunken father which means their safety is no longer guaranteed. This felt poignant as it shows how impressionable young people can be so drawn to power but they desperately need help from others when they are left powerless. It makes me think of this notable line in the story: “there was ‘neither good nor evil’, and that there was one law and one law only, that of the strong which dictated that ‘the stronger power was absolute.’” This feeds into what I perceive to be a larger message of the novel which is that all systems of order, government and justice collapse when all sense of morality disappears. What is right and wrong no longer matters because life in its rawest form is about survival of the fittest.

I found it absolutely chilling reading the account from the mob which Janos discovers describing their rampage through the city and how they preyed upon cats and a random family trying to get home. The extended terror they subject this family to taps into a sense of the perverse pleasure the powerful take in dominating and controlling those who are vulnerable. I didn't find Gyorgy Eszter to be sympathetic because of his selfishness and misogynistic attitude toward his wife (though, of course, she is a horrible individual.) However, it was touching how he realises his platonic love for his friend Janos and develops a deep concern for this wellbeing. Given his complete inability to protect Janos, I found it moving how Gyorgy resigns himself and takes solace in the music he loves. No matter how much he tried to block out the rest of the world (literally boarding up his windows and staying in bed as much as possible) his need for human contact and a connection with beauty took precedence. I wonder if this is a thin sliver of hope or a sense of humanity which the story offers amidst so much destruction. Nevertheless, the final section is one of the most sombre endings to a novel I've ever read.

I found the majority of this book alternately frustrating and intriguingly bizarre to follow. But mostly it gives this unsettling sense of the city and society breaking down on every level so I found it to be an intensely atmospheric experience. I'm sure it touches upon many philosophical ideas and concepts I haven't quite grasped or couldn't entirely follow. “The Melancholy of Resistance” felt to me like a cross between Cartarescu's “Solenoid” and Paul Lynch's “Prophet Song”. This is all extremely weighty and complex fiction, but I think they are books worth reading and taking the time to meditate on. Personally, I'm glad I read this novel though I realise it's not for everyone or, maybe, not the right kind of read for someone if they're not in the mood for it. I'd like to read more by Krasznahorkai but I need to take a break from him for a while.