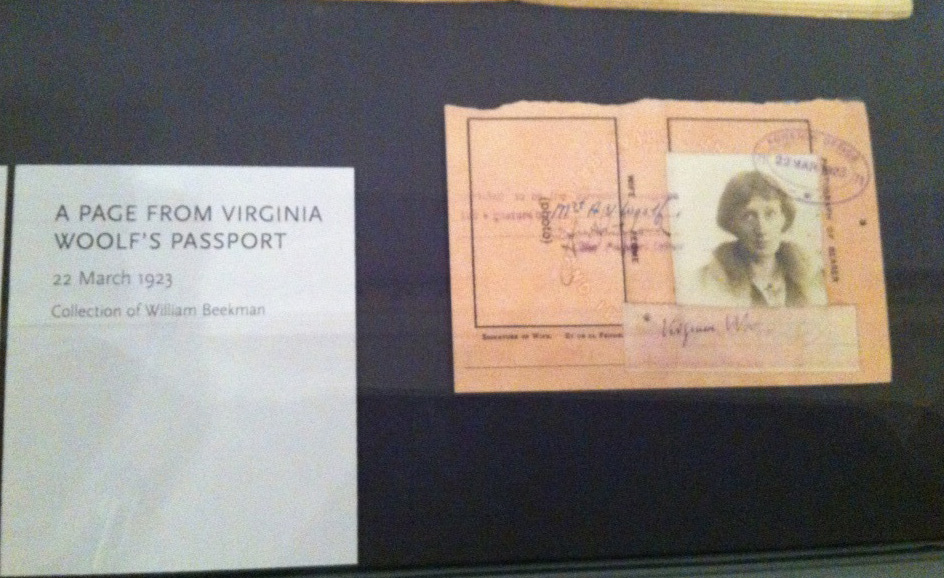

Woolf is an author I return to periodically because I know there’s always more to discover in her intricately layered writing. Rereading “Orlando” last year was such a joy and since “The Waves” is my favourite novel I’ll reread sections of it frequently. But I also recently received this stunning new manuscript version of “Mrs Dalloway” that’s been published by SP Books and it’s been absolutely fascinating reading through it. This is the first time Woolf’s hand-written manuscript of this novel has been reproduced and it’s incredible seeing her scrawls on the page, notes in the margins and lines she’s crossed out. It gives a captivating insight into her process of composing this pivotal novel.

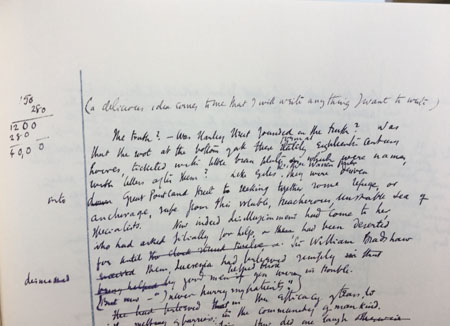

I’ve been discovering some interesting ways that this first version of the book differs significantly from the final book as well. Firstly, it was originally titled “The Hours” in honour of the structure she created of following her characters throughout a single day. Certainly the original opening is more overtly ponderous about the process of time as well and so radically different from the succinct opening of the published version of “Mrs Dalloway” which is surely one of the most famous opening lines in history. Secondly, it was originally going to focus on the character of Peter Walsh (the man who proposed to Clarissa when they were younger but she rejected him.) Clarissa was going to be more of a peripheral character as in the fiction she appeared in previously including Woolf’s first novel “The Voyage Out” and some short stories. But at some point in the process Clarissa took centre stage and the novel became titled with her married name. It’s also thrilling to see a note she writes at the beginning of one section that says “a delicious idea came to me that I will write anything I want to write.” I can’t help wondering what mental process she went through to come to this liberating conclusion!

It’s also quite touching seeing how laboriously Woolf crafted the novel. This should have already been obvious, but Woolf’s writing has such an assured intelligent quality to it that it’s easy to assume it simply flowed out of her purple-inked pen. This edition includes two introductions which provide some interesting context to the book’s creation. One is by Michael Cunningham who nicked Woolf’s original title for his own brilliant novel “The Hours”. The second is by Virginia Woolf-specialist Helen Wussow who lays out the manner in which Woolf wrote and the compelling history of the actual manuscripts after Woolf’s death. It was also interesting to learn how multiple final versions of “Mrs Dalloway” exist since she’d correct different proofs for different people – with alterations changing from manuscript to manuscript.

For a huge fan of Woolf’s writing like me, this book is such a treasure and one I’ll continue to enjoy reading through for many years to come. I also created a video showing off this beautiful book as well as giving my own little tribute to “Mrs Dalloway” by exploring her London: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w8sZGAHVVCw