As I discussed in my video about working on ‘Rediscover the Classics’ with Jellybooks, I have the exciting task of curating groups of classic books. My new selection has just been launched and it’s classic utopian novels! I’ve created original covers for all six of the books. You can see these covers, read more about them and join in here:

https://jbks.co/Utopia-reading-list

After registering for a free Jellybooks account you can select two free books from my selections to download and enjoy on your e-reader.

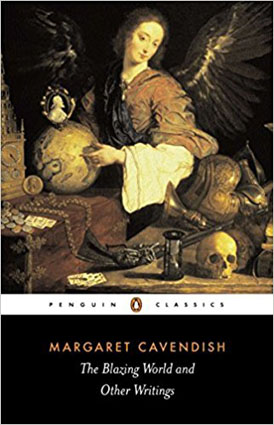

I’ve always had a fascination with utopian literature and read a lot of it during my teenage years – as well as the darker side of the coin: dystopian fiction! It’s tantalizing to imagine how we’d build a society from the ground up and that’s just what a number of authors have done through the ages. In doing so, writers inadvertently or intentionally reflect both their own values and the values of their time period. In many cases utopian fiction seems a way of criticising the etiquette, morals or laws of the age they were written in. For instance, Thomas More points out corruption in the Catholic church that was occurring in the 16th century; Charlotte Perkins Gilman cites the injustice of women’s dependence on men being the primary breadwinners; and, in satirising popular travellers’ tales of the early 1700s, Jonathan Swift ironically wrote one of the most beloved and imaginative episodic journeys of all time! Throughout Margaret Cavendish and Samuel Butler’s novels there is also an interesting engagement with emerging technologies and scientific advancements of the 17th and 19th centuries respectively. As well as being engaging and imaginative stories, the six books I’ve selected for this Utopian Classics reading group also offer fascinating insights into history and the way people from the past dreamily gazed into imagined futures.

It felt important to offer something of a balance (in gender at least) in choosing these utopian tales. The canon of classic literature is often top heavy with male voices and it’s exciting how there has been a recent resurrection of nearly forgotten female writers from the past such as Margaret Cavendish whose life was fictionally reimagined in Danielle Dutton’s fantastic novel “Margaret the First”. Many people will know Charlotte Perkins Gilman from her feminist classic “The Yellow Wallpaper” but not as many will have read her all-female utopian novel “Herland”. All of these novels also often hint at unconscious biases or dodgy ideas which many people will probably find appalling today. Slavery was an integral part of Thomas More’s utopia and Mary E. Bradley Lane vision of an all-female utopia was intentionally racist as it is composed exclusively of Aryan women. Rather than erase or gloss over these uncomfortable aspects of the fiction, I think it’s interesting to consider them in their historical context and just how much society’s ideals have changed since the time periods they were written in.