The shortlist for this year’s International Booker prize was announced online yesterday – the planned event for this had to be cancelled because of the global pandemic. If nothing else, recent events show how important it is for us to access literature from other countries to stay connected and in dialogue with each other during these uncertain times. It’s notable how the shortlisted novels reach out to many different corners of the globe including Japan, Iran, the Netherlands, Germany, Mexico and Argentina. The list is also largely populated by female authors and a few of the novels give radical new retellings of national myths, legends or origin stories. So I especially appreciate how this group of books gives voice to female, queer and working class perspectives from history which are often left out of historical accounts. You can watch my quick reaction to this year’s shortlist announcement in this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1udkZ9uMBTA

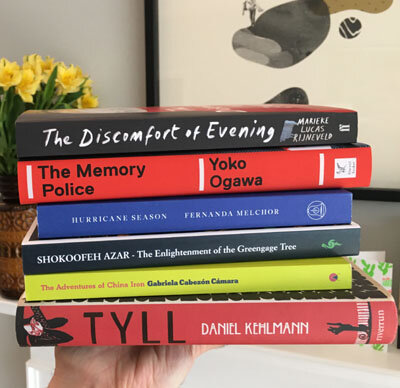

I’ve had the pleasure of reading a number of the nominated novels from the longlist over the past month and I’m delighted with the group of six novels the judges have chosen. Three in particular which stand out to me are the excellent historical novel “Tyll” which takes place during the Thirty Year War in central Europe, “Hurricane Season” which gives a panoramic look at life in a Mexican town centring around the death of an individual branded a witch and “The Memory Police” which creatively uses a dystopian story to ponder philosophical and psychological issues to do with memory. I enjoyed reading “The Adventures of China Iron” but had some issues with how fanciful the narrative became. And “The Discomfort of Evening” was an interesting book from a promising new writer but felt too meandering to come together for me. The only novel on the shortlist I’ve not read yet is “The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree” but I’ve heard such excellent things about this novel from other people who’ve read it that I’m greatly anticipating it now.

I was surprised not to see “The Eighth Life” on the list because I’m currently caught in reading this sweeping epic and I was disappointed that “The Other Name” wasn’t shortlisted as this is such a movingly meditative novel. But overall it’s an excellent list. Let me know if you’ve read any of these novels and what you think of them or if you’re keen to give any a try now.