It’s good that the day after the Booker Prize longlist was revealed, the shotlist for the Polari First Book Prize was announced at Polari’s regular literary salon held at the Southbank Centre. Concerns are rightly raised about the diversity of authors listed for any prize when announcements are made because it highlights how the industry and our society in general might be prone to elevating people of a certain gender, race, class or sexuality above others. The more prizes we have like The Polari First Book Prize (which honours debut books that explore aspects of the LGBT community), the more voices from all corners of our country are heard.

I attended Polari last night to hear the announcement and it was a pleasure to hear imaginative poet John McCullough read from his latest collection “Spacecraft”. His poem ‘Cat Flap’ went down particularly well with the audience. It was fitting to hear him read as his beautiful book “The Frost Fairs” won the prize in 2012.

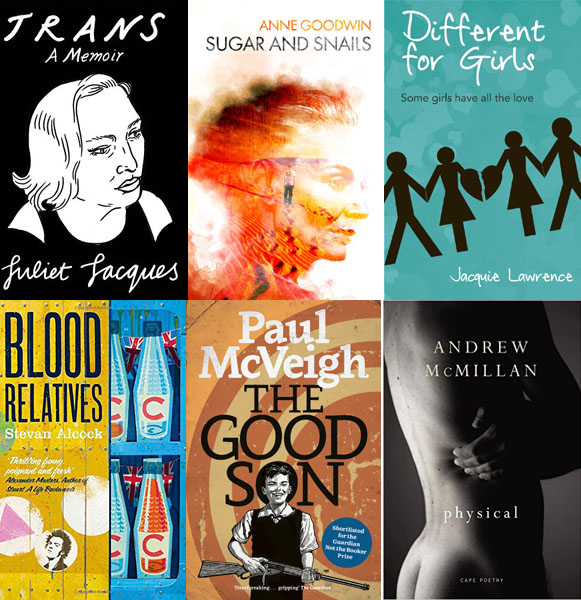

I’ve read three out of the six titles shortlisted for the prize and you can read my full reviews of them by clicking the titles below. Fantastic to see Andrew McMillan in the running for yet another award and his inclusion gives a nice continuity as he read at Polari when the 2015 shortlist was announced last year. Stevan Alcock also read from his gay coming of age novel “Blood Relatives” set against the backdrop of the Yorkshire Ripper murders. This makes a nice contrast to Paul McVeigh’s equally powerful coming of age novel “The Good Son” set in Belfast during the Troubles. Last night, Juliet Jacques also gave an excellent reading from her memoir “Trans” which gives a meaningful perspective on the everyday reality of a trans individual. I’m eager to read the other books on the list.

Have you read any of the below or are you interested in giving them a try?

Physical - Andrew McMillan

Blood Relatives – Stevan Alcock

Sugar and Snails - Anne Goodwin

Trans – Juliet Jacques

Different for Girls – Jacquie Lawrence

The Good Son – Paul McVeigh