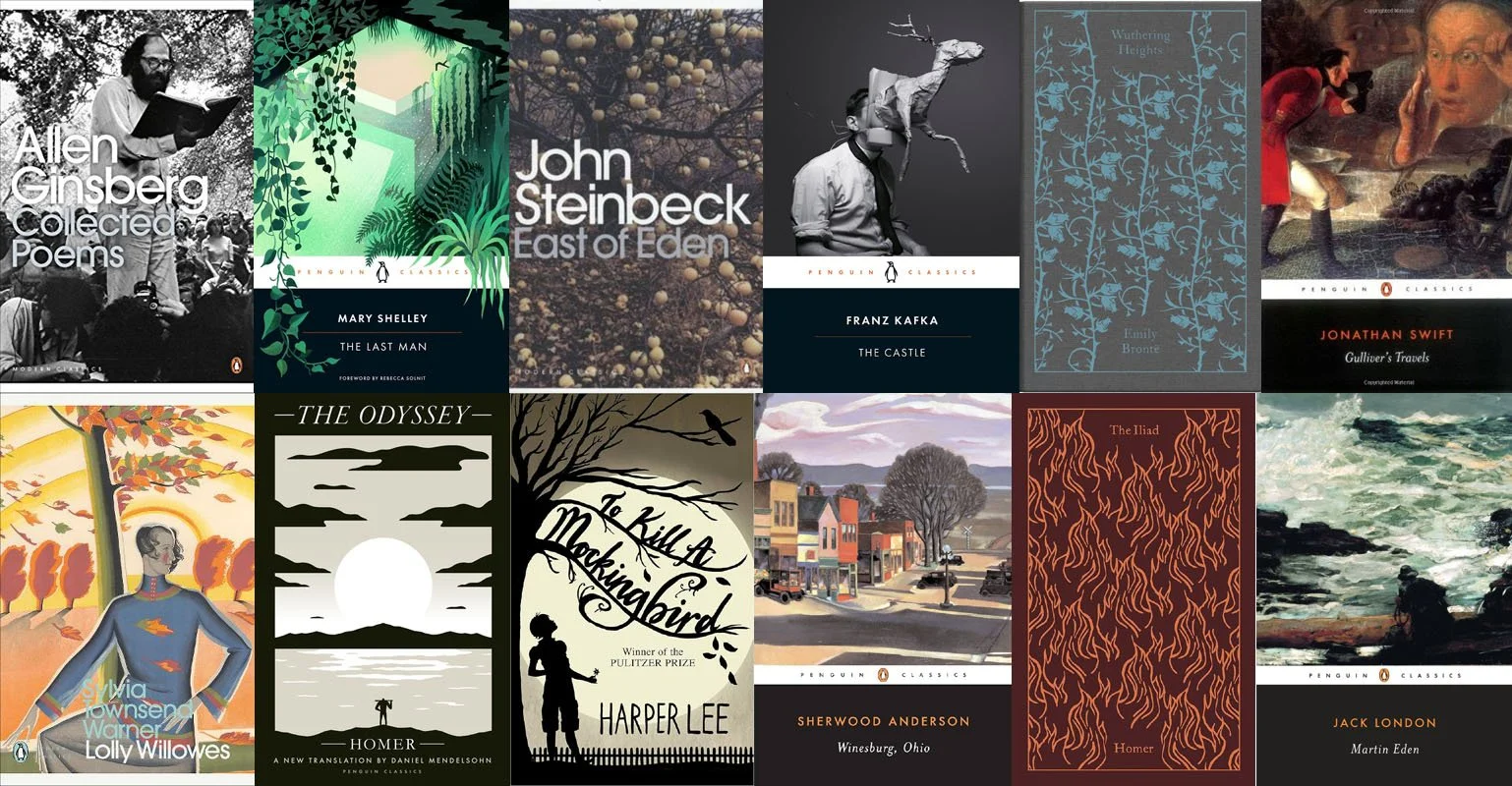

At the beginning of every New Year I like to set myself the challenge of reading 12 classic books over the course of the year. Many of these titles I want to get to in 2026 have a special anniversary attached to them based on their initial publication or the author's birth or there is a new film version of the book coming out soon. Have you read any of these classics or are you keen on joining me in reading them? Or are there any other classics you'd like to immerse yourself in this year?

Watch me discuss these titles and why I’m eager to read them in 2026: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7UMxKmokYa8

Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726)

This is a book often thought to be for children because of its many fantasy elements, but it was originally written as a political satire. It follows Lemuel Gulliver who travels to many distant and strange lands meeting tiny people, giants, civilized horses and other strange beings. The groups he encounters represent different forms of human nature and society. In doing so Swift explores issues such as government corruption, ineffective religious dogma and human pettiness. He shows that no form of government is ideal and that even bad societies contain good individuals.

The Last Man by Mary Shelley (1826)

I only first read “Frankenstein” a few years ago and think it is one of the most brilliant novels ever created. So I've been very keen to read more by Shelley and this book is considered one of the first dystopian novels. It begins in 2073 at a time when an apocalyptic plague has resulted in the near extinction of the human race. The story engages with new scientific ideas of the time concerning electromagnetism, chemistry and materialism. But it's also an extremely personal book as it contains a thinly veiled fictional depiction of Mary's late husband Percy who died in a shipwreck and their close friend Lord Byron who also died before this book's publication. I'm especially interested in reading this book because recently I read some of Muriel Spark's novels and a biography of her which describes her deep sense of kinship with Mary Shelley and fascination with this novel.

The Castle by Kafka (1926)

This was Kafka's final novel. It was incomplete at the time of his death and it was published posthumously. The story follows a character only known as “K” who arrives in a village and struggles to get access to the mysterious authorities who govern the region from a castle he's not allowed to enter. It's a tale about bureaucracy in government and religion, but it's also about solitude and the need for companionship. Kafka began writing this book in 1922 when he arrived in a snowy mountain resort that resembles the setting of the novel (Kafka can be seen in the far right of this picture.) He died two years later due to tuberculosis. I'm really keen to read this book after recently interviewing Mircea Cartarescu in the Penguin Classics library where he described how The Castle has been one of the most influential books in his life. If you want to watch my talk with Mircea I'll put a link to it below.

Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner (1926)

This satirical novel is considered an early feminist classic. It's set in the early 20th century and follows a middle aged spinster named Laura Willowes who moves away from her controlling relatives to take up the practice of witchcraft. In doing so it considers the social restrictions placed upon women at the time and the uneasy position women held in society following WWI. This was Warner's first published novel and she was a fascinating writer who spent most of her adult life in a romantic relationship with a woman. She had a long and varied writing career and I've previously read her historical novel “Summer Will Show”.

Sherwood Anderson (born 1876)

Born 150 years ago in September 1876, Anderson was a self-educated American novelist most famous for the short story cycle “Winesburg, Ohio”. This is set in a small fictional town where each story follows the personal dramas and inner turmoil a different citizen. But the book centres around the life of a character named George from his childhood to adulthood and ultimate decision to leave Winesburg. These stories are about the difficulty of communicating with others and the isolation of small town life. Some have described this book as gloomy but that sounds very much like my vibe. One of my favourite novels from last year was Buckeye and this book's style has been frequently compared to Sherwood Anderson's so it's made me even more keen to read this earlier book.

Jack London (born 1876)

Another great American writer born 150 years ago was Jack London. He was a journalist and activist who felt passionately about animal welfare, workers' rights and socialism. One of his most famous books is “White Fang” which follows the perspective of a wolf-dog in the harsh environment of the Yukon and the violent world of humans. However, he also wrote a semi-autobiographical novel “Martin Eden” which follows a seaman who is desperate to become a literary success. Many young writers consider this a kind of guide to getting published as its protagonist continuously sends out his manuscripts, but London intended this as a criticism of ambition. I read it when I was a teenager and loved it, so I'm keen to see how my views of it might have changed. A few years ago I visited Jack London's ranch which he desperately tried to make a success but it was an economic failure and it's where he's buried having died at age 40.

Harper Lee (born 1926)

Harper Lee was born 100 years ago in April, 1926. They seem to keep publishing more books by Harper Lee though she's really famous for her Pulitzer Prize winning novel “To Kill a Mockingbird”. This Southern Gothic classic about racial injustice, class, gender roles and the courage to stand up for what's right. Its girl narrator Scout is an irrepressible force of nature and it's so compelling viewing the world through her point of view. I loved reading this book as a teenager so I'm keen to revisit it now – especially after reading Truman Capote's novel “Other Voices, Other Rooms” recently. Capote and Harper Lee were childhood friends and Capote's debut includes a fictionalised version of Harper Lee as a tomboy girl.

Allen Ginsberg (born 1926)

Poet and activist Allen Ginsberg was also born 100 years ago in June 1926. He was famously one of the core members of the Beat Generation who held strong views on drugs, sex, Eastern religion and who were strongly opposed to bureaucracy. His most well known poem is 'Howl' which embodies the values and history of the Beats but he wrote many more which draw upon a wide range of knowledge and ideas. I've always been slightly intimidated about approaching his poetry for some reason (maybe because his collected work is so long) but I think it'll be a pleasure dipping into reading a few poems during some mornings over the course of the year. This is also another book that Mircea Cartarescu cited as a primary influence in my talk with him.

Iliad (because of Yann Martel’s upcoming new novel Son of a Nobody)

This is one of the oldest works of literature that's still widely read and is thought to have been composed in the 8th century BC. It's a Greek epic poem set towards the end of the Trojan war and a 10 year siege of the city of Troy by the Myceneans. It also details the fierce quarrel between the warrior Achilles and King Agamemnon following the death of Achilles' beloved prince Patroclus. Of course I was a huge fan of Madeline Miller's novel “The Song of Achilles” and loved going to the Punchdrunk immersive theatre experience ‘The Burning City’ which is set within the fall of Troy. So it'll be fascinating to read this epic which has been so influential throughout all of Western culture.

The Odyssey

Then there is Homer's other great epic “The Odyssey”. One of the biggest film releases of 2026 will be Christopher Nolan's version of this story with an incredibly starry cast including Anne Hathaway, Matt Damon, Tom Holland, Zendaya and the fabulous Mia Goth. This book is one of the greatest adventure stories of all time as it traces Odysseus' journey home after the Trojan War which takes ten years while his wife Penelope waits at home weaving away. It'll be so exciting and satisfying to completely immerse myself in this equally influential tale. And this is a book I tried reading as a teenager but didn't get much out of so I'm hoping the fact that I'm older now and that I'll be reading this more recent translation by Daniel Mendelsohn will mean I get more out of it.

Wuthering Heights

Another film coming out in 2026 which is already infamous is the latest adaptation of Wuthering Heights by Emerald Fennell. Many booktubers and booktokers have already trashed this latest film starring Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi just based on its trailer. It's made me perversely even more eager to watch this movie to see what I make of it. But I read this novel for the first time several years ago and found it so strange and intriguing. It's considered by many to be one of the greatest romances ever but it's also an anti-romance. It's poet Emily Bronte's only novel. Set on the wily windy Yorkshire moors it relates the story of Cathy and Heathcliff's turbulent affair. This story is so complicated and odd I think it can be reread countless times and there will always be new meaning found in it.

East of Eden

I really love a good family saga and one of the greats is by Nobel Prize winner John Steinbeck. He considers it one of his best books as he once said "It has everything in it I have been able to learn about my craft or profession in all these years" and "I think everything else I have written has been, in a sense, practice for this." The story follows the intertwined destinies of two families in California from the beginning of the 20th century to the end of the WWI. There are many religious references woven into the novel, but it also captures something quintessential about American life. I've read a couple of novels by Steinbeck but not this one and I love the humanity in his characters and stories. This book has also been turned into a new miniseries starring Florence Pugh and Martha Plimpton. Of course, I want to read the book before watching the series.