Growing up in an upper/middle class family in Chicago in the 50s & 60s, Margo Jefferson was subjected to unique pressures from within her household and the community around her. She felt self conscious about inhabiting a space in society she refers to as Negroland – a particular socio-economic group of well-educated and financially secure black groups cornered by certain social perceptions. They felt they couldn’t fully be accepted into white society nor did they want to be associated with what were perceived to be lower class/uneducated black people or what Jefferson terms “lowlife Negroes.” This created an intense form of self consciousness where Jefferson felt stuck between assimilating into the white culture including pressures to modify her appearance to look white and separating herself from society’s expectations about how she should appear and act. She states “We knew what was expected of us. Negro privilege had to be circumspect: impeccable but not arrogant; confident yet obliging; dignified, not intrusive.” Jefferson goes on to eloquently describe the historical conflict faced by privileged African Americans and meaningfully conveys the internal struggles concerning racial identity that she’s experienced throughout her life.

It’s fascinating how she connects feelings of self consciousness about privilege throughout generations since American slavery and cites different examples of how different black individuals in positions of power have either reinforced these notions or worked for social progress. She describes how “The secret signal which one generation passes, under disguise, to the next is loathing, hatred, despair. And as a result of these, a sense of perpetual violation.” However, because of social expectations from within and outside of the black community these feelings that Jefferson had could never be expressed and only internalised: “With external failure out of the question, internal discord seemed the only protest mode.” They lead her to some very dark and heartrending moments in her story.

Of course, feelings of segregation based on racial difference were only part of the difficulties of development that Jefferson experienced – something she readily acknowledges. This was a time period of many radical social changes and issues of anti-semitism, sexism, classism and homophobia were also prevalent. It’s interesting and sympathetic how Jefferson acknowledges throughout her memoir the complexity of identity. It’s also touching how unwilling she is to give into self pity and maintain a tough critical distance from the deep emotional hurt she experienced while still making the reader achingly aware of the power of her feelings.

Some of the most wonderful sections of this memoir are Jefferson’s recollections of her development as a reader. She sharply critiques Mark Twain and James Baldwin while identifying strongly with the intense world of Louisa May Alcott’s “Little Women”. Early on in her learning, she rejected male-dominated fiction: “I was a jealous little she-reader; I resented pouring myself into the lives of hero-boys.” Where Jefferson thrived the most is when she identified the writers and cultural movements that she related to and that inspired her the most. She drew particular inspiration from jazz artists and a beat generation which she could feel a part of without letting it define her: “I was trying to enter a world tied to my history but not my autobiography.” Radical movements were necessary to push the kind of social change that could allow ambiguity and individual voices to emerge: “The world had to upend itself before shades of possibility between decorum and disgrace could emerge.”

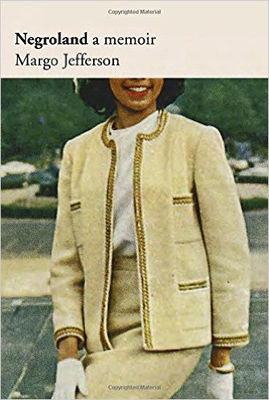

Ad from Ebony Magazine. Jefferson writes: You will never be the fair sex, but you strive to be an ever-fairer one."

While reading this I was reminded of a literature course I took once where a white teach was giving a lecture about the writer Jamaica Kincaid. She lamented that Kincaid’s more recent work focused on her passion for gardening (something the author acknowledged was inherited from a European tradition). My teacher said she felt the author was trying to be white writing about such a subject instead of focusing on colonialism and racial issues in the Caribbean. I didn’t know how to respond at the time but it feels to me outrageous now that she felt Kincaid should limit herself to a certain kind of writing or not allow herself to take pleasure in activities which didn’t originate from the culture she was born into. It’s terribly elitist and makes me wonder how in some ways “higher education” might reinforce particular kinds of division.

The way that language is used concerning race is a touchy subject. Just by titling her memoir “Negroland” is something which will no doubt provoke an emotional response and I must admit it made me feel self conscious reading the book in public. What might someone think it's about glancing at this title? This is the point. Jefferson means to provoke thought and discussion about the subject – something which is ongoing and necessary. It’s a tremendous strength of this book that it doesn’t lapse into didacticism, but instead prompted me to feel more awareness of how people might or might not change their behaviour based on racial differences. It made me think about how marginalized groups in our society don't all exist on one level but inhabit different spheres of repression and discrimination. It's also striking the unique perspective Jefferson gained from inhabiting a particular group: “Being an Other, in America, teaches you to imagine what can’t imagine you.” This is a powerful and thought-provoking memoir.