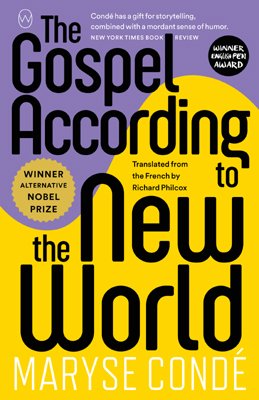

Maryse Condé has been alternately dubbed the Grand Dame of Caribbean Literature and the Queen of Caribbean storytelling. She is a prolific novelist and critic from Guadeloupe. Her numerous books have often explored the African diaspora that resulted from slavery and colonialism in the Caribbean. Now, in her late 80s, she’s written what's said to be her final novel “The Gospel According to the New World” which is longlisted for the International Booker Prize. It's a parody of the New Testament in which we follow Pascal, a mixed race boy born in contemporary Martinique. He's abandoned at birth and his adventures play upon the life of Jesus. Many of his experiences and the people he encounters have direct correlations to the bible. Numerous occurrences involving Pascal are rumoured to be miracles – though there's little evidence to prove this. As such, he acquires a devoted following and group of disciples as well as many detractors. Although he was adopted, Pascal embarks on a quest to discover his true parentage: his birth mother who converted to Islam and his father who is a guru that runs an ashram. As he travels to many locations he also engages in a number of affairs with women which often end in disappointment. By drawing upon a number of different religions to inform his journey, Condé questions what the role and purpose such a messianic figure might have in the modern world.

This novel is fairly readable with evocative descriptions and it contains some interesting ideas. But the structure doesn't allow them to be developed enough. Since it sets out to self-consciously present an exaggerated version of events from the Bible it begins to feel routine. It cycles through variations of Lazarus being raised from the dead, the sudden appearance of multiple loaves of bread to feed a wedding crowd and a form of the last supper where Pascal washes the feet of his apostles. This quickly grows tiresome and feels a little too on the nose – especially because Pascal himself so often comes across as naïve, hapless and dull. He has banal epiphanies which show his outrageous ignorance such as “He had thought India was a land swarming with men and women sentenced to a life of famine. On the contrary, he had been dazzled by its extraordinarily rich culture. He had also realized the diversity of the world and the complexity of its problems.” While I'm guessing this is satirising his small-mindedness it makes it difficult to empathize with him at all. There are some other more interesting characters such as his adoptive mother Eulalie who enjoys attention from the press and his charismatic and ambitious gay friend Judas who Pascal might have some romantic attraction towards. Potential storylines are rapidly abandoned such as when a mute boy named Alexandre goes missing after Pascal is charged with caring for him. The novel moves on at such a pace that these potentially compelling dynamics aren't fully explored.

There's an uncomfortable relationship between this novel and the religious text it draws inspiration from. Christian holidays and the life of Jesus are acknowledged, but no one in the story seems to note the increasingly ridiculous parallels between the lives of Pascal and Jesus. For instance, at one point Pascal is approached by the equivalent of Mary Magdalene and Judas objects to fraternizing with her. Condé writes “Pascal replied absentmindedly and in a gentle tone: 'Let he who has never sinned cast the first stone.' Used to his mysterious and incomprehensible words, Judas Eluthere made no objection.” Why would this statement (one of the most famous lines from the New Testament) be “mysterious and incomprehensible” as Condé's character must be familiar with the Bible? I know this novel is written as a parody but it's difficult to gauge by the tone of the story what relationship the characters and situations are meant to have with the real world. So, in following the New Testament so closely, this novel doesn't come across as refreshing or emotionally involving enough.

Similarly, people rally around Pascal as a new messiah but there seems to be little justification or reasoning for them to believe he'd be this. References are made to Pascal teaching classes and assembling disciples but it doesn't feel like this would be far-reaching enough to invoke the kind of near hysteria from his followers around the world which is occasionally mentioned. There's the potential for his life and message to reach more people with a television debate (which doesn't materialize) and a self-published memoir (which is badly reviewed). At one point it's remarked “Why did he arouse so much excitement? Why did the unlikely adventures of a new messiah destined to harmonize the world get so much coverage? Why did some people take sides with him while others held him to public obloquy? People were nurtured by a void and a malaise that no elections by universal suffrage could satisfy: they felt that neither the elected nor their ministers represented them.” This is an interesting statement but it doesn't show the reader any tangible reasons why we should believe that so many people would rally around Pascal except through local rumours. For example, it felt like Condé could have built upon this being a modern story with his fame being spread on the internet and social media.

Perhaps none of this lack of realistic detail should be taken seriously, as the novel could simply be read as a satire about how any messiah that appeared today with a well-intentioned message of peace would be hopelessly overwhelmed by the complexity and nuance of problems in the modern world. Unfortunately, I don't think this needs to be stated in novel form as it mostly comes across like a simple conceptual exercise without enough humour or wit. There's a character named Roro Maniga who is “well known as a painter and his paintings were extremely popular since they were an explosive mixture of sacrilege and religious beliefs. For example, he had painted a series entitled Virgin and Child, where one canvas represented a Black woman, one an Indian woman, one a Dougla, a Chabeen, a Capresse, a Mulatto woman, and finally an Octoroon, each holding a lovely Black infant.” It's an idea worth stating and it feels like Condé is doing something similar in her fiction by presenting Pascal with his mixture of heritage as a modern Jesus. But I'm not sure this novel conveys anything beyond this fully justified perspective which diverges from traditional representations of the messiah. If it's saying that we're not progressing as a society as much as we think we are it's only pointing out examples that are already obvious.

Many notable writers such as Jose Saramago, Philip Pullman, J.M. Coetzee, Norman Mailer and Colm Toibin have felt compelled to write fictional variations on the life of Christ with varying results. Perhaps authors who reach a certain stature feel it necessary to comment upon the modern meaning and questionable relevance of one of the most influential religious stories. In the end, I feel like Condé's text is more like an interesting exercise rather than a satisfying novel. It's perhaps unfortunate that this is the first book I've read by her. I am definitely keen to read some of the more famous books from her back catalogue as her writing clearly contains a sly sense of humour and a different perspective. However, reading this novel on its own comes across like a box being ticked.