How could I not fall for a novel whose plot superficially resembles the movie 'Ghost'? That's not to say this book was inspired by that film as its use of ghosts caught “In-Between” is rooted in Sri Lankan folklore, but it's the reference which immediately came to my mind when reading this tremendous story. There may not be any Oda Mae Brown, but there is a more sinister self-interested sort of medium called The Crow Man. Thankfully the protagonist is also much more interesting than the blandly good, pretty boy Sam Wheat. Maali Almeida documents atrocities of war and wants tyrants to be held accountable but he is not virtuous. From page one it states that if he had a business card it'd say: “Maali Almeida: Photographer. Gambler. Slut.” He accepts work from shady organizations, loses a lot of his money at a casino and sleeps around with many men behind his (secret) partner DD's back. What's more he's disillusioned with the government and doesn't attach himself to any particular political organization in Sri Lanka which is heavily embroiled in a deadly civil war during the late 80s when this novel is set. Because of all his complexity and so-called “flaws”, I fell in love with this character.

At the start of the book Maali wakes to find himself in the liminal space between life and the great beyond. Just like we can't recall birth, he can't recall his death. He's instructed by an official that he has seven moons to decide whether he wants to enter the light or remain as a spectre amongst the living. A countdown begins during which he wants to discover his killer, reconnect with those he loves and reveal to the public shocking evidence of a national scandal. It's satisfying reading a novel built around a certain structure that moves towards a definite ending and the suspenseful way in which this story unravels makes it thrilling to reach the conclusion. We gradually discover details of his life through people he “haunts”, but he also encounters many of the dead victims he got paid for photographing. In addition to those who were actively killed there are the ghosts of those who found life in Sri Lanka untenable and committed suicide. These spirits are raging. There is a tension between those who want to get their revenge and the desire to leave all the pain of life behind.

This is dramatically played out over the course of the novel as Maali becomes familiar with Sena, a deceased man who is hatching a terrorist plot aided by a dangerous, demonic spirit. Underlying these tense and fantastical events are deeply pressing questions about our degree of involvement to enact change and our motivations in life. Maali has seen enough deception, hypocrisy and double-crossing coupled with egregious acts of oppression and mass murder to know that no leader, political organization or band of people can be trusted with consistently safeguarding the welfare for everyone in his country. A brief list of the primary political groups involved in Sri Lanka's conflict is given towards the beginning of the novel. This not only slyly tips off Western readers to who the main stakeholders are and the general motivations of these groups but also shows how none of these opposing forces are purely “good” or “right”. Not aligning himself with any of them makes him an outsider, but he also feels like an outcast because he's a closeted homosexual. Experience has taught him it's safer to adamantly deny being gay even when it's clear he's not straight. His infidelity and many furtive sexual encounters are partly caused by this social pressure but also his puerile justification that it's man's nature as shown in this funny exchange: “You tell him the pecker is proof that man has no free will. There is a pause and, then, DD snorts: 'That is the lamest excuse ever.'”

The story is narrated in the second person which makes sense for a protagonist who has been separated from his physical body. It also grounds the reader in Maali's immediate experience as he struggles to navigate the laws and rules of this peculiar afterlife. The means by which he travels through wind and the degree to which the dead can whisper to the living or physically interact with them are bound by certain constraints. This is handled quite playfully with evocative details such as what it feels like to walk through a wall. It's also amusing how the transitory space which is meant to encourage him into the light resembles an overworked bureaucratic waiting room and ghosts do prankish things like make a scientist's bum itch. So the story doesn't often feel too hampered by logistics and there were only a couple of scenes where it felt like the author was heavy handedly whipping Maali's ghost to a particular place to advance the plot. However, the way in which the afterlife is layered over the realistic world is also presented in a genuinely creepy and atmospheric way. At one point this is even made personal to the reader when it's observed: “There are at least five spirits wandering the space you're in now. One may be reading over your shoulder.” Terrifying and twisted spirits frequently appear to Maali and that initial horror is deepened by the tragic backstories that accompany many of these pitiable souls.

Maali still has the impulse to document what he witnesses and the novel frequently refers to how he continues trying to take pictures with the camera around his neck even though the device is muddied and broken. There's a poignant tragedy to this and the race to allow incriminating photos he took to be seen by the general public. These aspects of the story challenges the general sense that if we can witness any wrongdoing in the world it will be corrected. It's revolutionary how images and video filmed by ordinary people which become viral inspire protest and movement towards change. However, there's also a danger that we can become numb to such violent imagery because of our distance from it and a sense of hopelessness. Can an overwhelming amount of individual tragedy be met with anything but inertia? This novel intelligently probes these issues while not allowing the central suspenseful plot to be drowned by them.

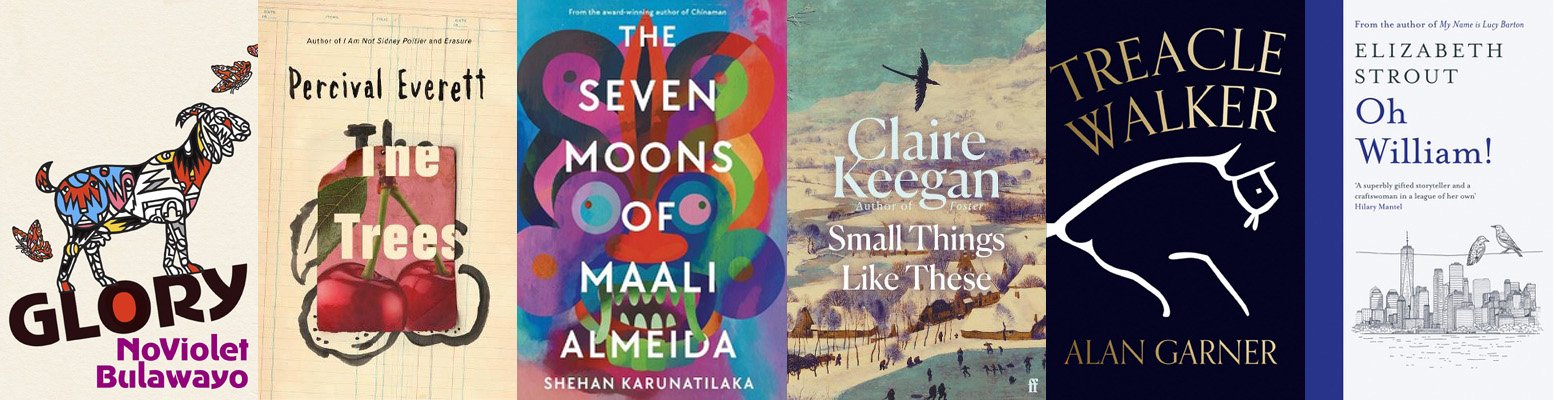

My affection for the central character was also formed because of the love triangle at the centre of this novel. Maali doesn't only live with the equally closeted politician's son and golden boy DD who is described as a “former swimmer, athlete and ruggerite” but also DD's cousin Jaki who has a misplaced attraction towards Maali until they settle down to become good friends. The dynamic of this trio is presented in a compelling and charming way. There's a persistent tragic sense that Maali and DD's dreams of moving to San Francisco to live freely and openly will never be realised. This is underpinned by recollections of endearing moments such as how they had “a hall lined with books that you and DD have gifted each other for misremembered birthdays. Neither of you have read the books received as presents, only the ones you bought for the other.” All these elements combine to produce a big emotional impact. I admire how this novel manages to be mischievous, thrilling, unsettling, insightful, moving and so much fun to read. It's also interesting how the book was originally published in India in 2020 with the title “Chats with the Dead”. Now that it's been published in the UK and has been longlisted for this year's Booker Prize the novel is getting a second life – which feels pleasingly appropriate given the nature of its story.