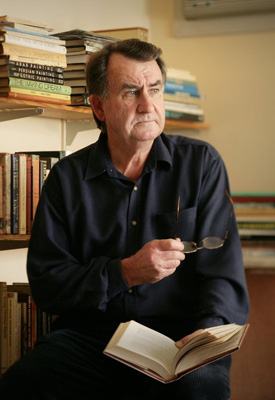

The title of Michael Fuller’s memoir “Kill the Black One First” is a startling statement - as it’s meant to be. This was something which was shouted by the public while he was the sole black police officer in a group of white officers trying to keep the peace during the Brixton riots in 1981 (an infamous confrontation amidst racial tension between police and protesters in South London that led to many injuries and widespread destruction.) The phrase epitomises the dire dilemma Fuller found himself in for much of his life working for the Metropolitan Police where he was often subjected to racism from within the predominantly white police force on one side and suspicious anger from sections of the black community who labelled him “coconut” on the other. Fuller recounts his life from his beginning growing up in a care home in the 1960s to eventually being appointed the first black chief constable in the UK in 2004. This is the story of a diligent, bright and sensitive individual who cares passionately about justice. Being a good conscientious police officer was his primary motivation in life. But, because of the colour of his skin, he faced innumerable obstacles which would have deterred many from pursuing this profession or abandoning it (Fuller highlights how few black police officers made a career at the Met due to feeling so isolated.) His journey is utterly inspiring and it powerfully illuminates the dynamics of racial conflict in England over the past fifty years from someone who was in a very unique position.

At the heart of Fuller’s journey is a quest to belong. Margaret, the young woman who ran the care home he was raised in for much of his childhood provided him with crucial guidance which gave him a strong moral core and taught him to “recognise that something’s offensive without being hurt by it. Stop. Think. Decide how you want to react.” This is a somewhat more constructive variation from what RuPaul’s mother famously advised him as a child: “People have been talking since the beginning of time. Unless they’re paying your bills pay them bitches no mind.” Anyway, Margaret’s advice proved invaluable throughout Fuller’s life as he encountered assumptions, prejudice and hatred from many people who seemed to believe that racism was an unchangeable part of English society. Fuller learned not to lash out when confronted with these dogmatic beliefs as it wouldn’t be productive and distance him from his fellow officers: “It made me wonder if I should speak up more often when, for example, my colleagues used racist language. But that could only create divisions, and I had spent the year trying to fit in with my shift, laughing and joking with them and not calling them to account.” However, this also created a tremendous mental burden and feelings of intense loneliness as he was often maligned by both the predominantly white police force and the black community. It sometimes lead him to feel he didn’t belong anywhere and he’s made painfully aware that “I’d been isolated by my colour all my life.”

Anyone who has encountered prejudice or injustice knows how one of the most debilitating consequences of it is how alone it makes you feel. Fuller observes how “Racism is a painful, humiliating thing to experience but the key to that pain is isolation. When others protest, offer support, turn that isolation back on the racists, the pain is greatly eased. Feeling alone with the hurt is far, far worse.” There are several instances where people realised that Fuller was experiencing racial abuse, but failed to speak up and defend him. It takes a lot of conviction to stand up to a bully when you’re not directly involved in the conflict. Probably all of us have experienced prejudice in some form and no one witnessing it intervened. We’ve also most certainly witnessed someone being victimised and not come to their defence. It’s one of the most challenging aspects of being a participant in society. But thankfully Fuller found some allies along his journey who were prepared to stand up to racism alongside him.

When he was just beginning his career Fuller’s father and friends mocked his desire to become a policeman: “You’re joining the police because you hate injustice! The police ARE injustice!” It’s heart breaking reading about the derision he faced when walking on the beat: “young, black males remained by far the most aggressive demographic towards me.” He faced a long challenging journey to help restore the public’s faith in the police force and institute changes within the police so that officers didn’t practice racial profiling or discrimination. He was instrumentally involved in landmark changes such as installing CCTV cameras in investigation rooms, using computers to look for crime patterns, instituting changes to prosecute hate crimes and helping the community and police to work together through an innovative initiative called Operation Trident. This involved a great deal of creative thinking and personal sacrifice as he frequently put himself at personal risk. It was also an unanticipated extension of his duty and drive as a policeman which was to catch criminals. It shows how police work is a much more complicated and nuanced job than that.

Fuller recounts many dramatic scenes and emotional encounters when reflecting on his long and distinguished career. It was shocking to learn how apathetically some policemen reacted to crime when they knew there was little chance of resolution or conviction – especially with instances of domestic violence or gang-on-gang warfare. An inconceivable amount of resolve was required to stay dedicated to his profession and maintain an active role in helping every victim of a crime. It’s also sobering to realise how the police force and country might not have benefited from his skills in bettering our communities if he’d found venture capitalists willing to take a punt on a very savvy business plan he formulated at one point to open a chain of coffee shops in London (before this became a booming business in the city.) Thankfully he remained with the Met and rose in the ranks to a point where he could implement changes that have utterly transformed police-community relations. He also serves as an invaluable figure of inspiration and hope. The full circle journey Fuller takes us on throughout this memoir is executed with considerable skill, but more than anything I feel in awe of this good man and loyal police officer.