Some books leave you reeling in astonishment and “A Brief History of Seven Killings” certainly does that. I feel like I've been startled awake and can still hear the multiplicity of voices contained in this novel. Marlon James creates several distinct narrators to tell the story surrounding an assault upon Bob Marley’s house on December 3, 1976 by unknown gunmen who attacked Marley, his wife, manager and band mates which left them seriously injured. This mysterious incident occurred two days before he was due to sing in a concert which was meant to inspire peace between two warring Jamaican political groups. Nevertheless, Marley performed at the concert as scheduled. This novel is told from the point of view of dons (or territorial/gang leaders), CIA agents, a journalist, gang members, a woman trying to escape Jamaica, a hit man and a deceased politician. It spans a decade and a half from 1976 to 1991. It is specifically about the Singer and Jamaican politics, but it’s also a fantastic exploration of identity (national, racial, gender, sexual, spiritual). This is a book that challenges your assumptions about who you think you are and how you see other people.

Although Marley is central to the story we never get his voice. As such, the characters talk about him and (in some cases) directly to him, but we don’t hear his point of view. This is important because, as the novel progresses, it becomes about much more than the incident and extends its meaning into the larger culture. The author could very well be revealing his mission for this novel when a character states at one point: “there’s a version of this story that’s not really about him, but about the people around him, the ones who come and go that might actually provide a bigger picture than me asking him why he smokes ganja.” In this way, Marley is mythologized in a way similar to what Gabriel García Márquez does in “Chronicle of a Death Foretold” where the murdered man central to the story becomes so filled with all the characters’ opinions about him that he ceases to be a physical man and becomes more of a symbol. At the same time, I felt incredibly anxious for and sympathetic towards Marley’s plight as he was caught in an overwhelming web of scheming and ideological battles. He was extremely vulnerable as one man observes: “Once you climb to the peak of the mountain, the whole world can take a shot.”

As well as offering a wide range of perspectives on Marley, the novel also gives a fascinatingly complex understanding of race as viewed from the perspectives of multiple characters. There is the white journalist Alex Pierce who scoffs at white Americans who affect black sensibilities, but who can’t fully integrate into the society. Or the CIA man who observes that “Racism here is sour and sticky, but it goes down so smooth that you’re tempted to be racist with a Jamaican just to see if they would even get it.” Throughout the book there is an awareness of skin colour being a factor in social class depending on lightness or darkness. An enforcer and don, Josey Wales, states that “In Jamaica you have to make sure that you breed properly. Nice little light browning who not too dry up, so that your child will get good milk and have good hair.” These points of view bring to mind for me Chimamanda Adichie’s observation that race isn’t a genetic issue, but a social issue. There are conflicted levels of racism inherent to everyone’s point of view which are demonstrated by the way they interact with and think about others.

For a novel so dominated by a multiplicity of male perspectives, the female narrator Nina Burgess gives a refreshingly different take on women in this novel. She’s someone who I felt a tremendous level of sympathy with both for her yearnings and her need to escape her culture to create a new identity. Burgess exposes the sexism women must face in Jamaican society – how the threat of sexual violence is something which can go unreported and be overlooked by officials even if it is (as they may very well be the perpetrators.) It shows how fear of it can be a kind of torture: “I can’t imagine anything worse than waiting for a rape.” It’s shown how rape is used as another instrument of war and the quest for domination. Importantly, the novel also shows how stereotypes or expectations about the way women might be treated in Jamaica don’t always play out in the ways you’d expect in specific circumstances. Another female character who defies stereotypes is Griselda Blanco, a drug lord who is one of the toughest and most fearsome characters in the entire book.

At the same time, James gives a sympathetic understanding towards his male characters – even when they are ruthless killers. Many feel trapped by circumstance and cornered into taking certain actions based on what opportunities are available to them. Some experience a crisis of consciousness and develop or recess back into old habits of being. The character of Josey Wales meaningfully realizes that “When you come into the real truth about yourself, you realize that the only person equipped to handle it is you.” There aren’t avenues of support to encourage gang members out of the life they live. The horrific fact about the violence that many of the men engage with is that it is self-perpetuating and has no end: “The problem with proving something is that instead of leaving you alone people never stop giving new things to prove, harden things.” So the violence must escalate as the men feel they must maintain and protect their place within their social group.

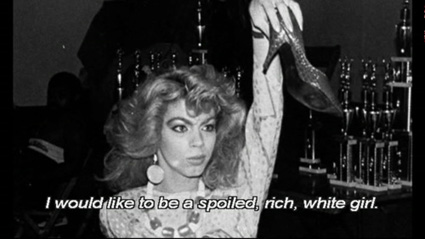

Jamaica has a notoriously bad reputation for the way it treats its queer community. That rampant homophobia is reflected in this book where one of the most common insults casually doled out is “batty man.” This isn’t surprising and fully justified given that many of the voices are by macho tough men. What is surprising is that two of the voices (that of a complicated gang enforcer named Weeper and a dangerous hit man named John-John K) are men who actively have sex with other men. There is a level of acceptance for their actions by some gang members who acknowledge their different sexuality but overlook this fact because they don’t consider them “that” type of gay man. Equally there is a complex understanding of their own sexualities within each man’s narrative. They challenge stereotypes: “Don’t think the man getting fucked must be the bitch.” Bottoms can also be bad ass.