This has been a year of great personal change for me. More than ever, I'm aware of how books work like a conversation informing our lives and that it's important to talk back. (This blog is me talking back.) My reading this year increased somewhat largely because I joined in on a shadow jury for the Baileys Prize and as a judge for this year’s Green Carnation Prize. I read 96 books in total, but this doesn’t count the dozens of books I started but put aside after fifty or even two hundred pages. I’ve become more cutthroat because the truth is there isn’t enough time to keep reading a book that’s not doing it for you. You might not connect with it only because of where you are in your life, but I think it’s best to move onto something you feel passionately engaged with rather than slogging through something you feel you should read. There are rare examples like “The Country of Ice Cream Star” which took me longer to read than any other book this year and which I found incredibly difficult. Ultimately it was rewarding and I’m glad I stuck with it till the end, but such cases are rare.

There are dozens of really superb books I’ve read this year. I’m always passionate about reading short stories and the books I’ve read by Donal Ryan, Tom Barbash, Ali Smith, Mahesh Rao, Stuart Evers and Thomas Morris all contain stories which have really stuck with me. Because the Green Carnation Prize is open to books in all genres, I also read more memoirs, young adult novels, poetry and nonfiction than I usually do. I hope to continue reading more widely as some of these books like Erwin Mortier’s profound/heart-wrenching memoir and Mark Vonhoenacker’s meditation on flying have been truly fantastic.

Book podcasts have also been a welcome new presence for me this year. I’ve always avidly listened to The Readers, hosted by two of my favourite book bloggers. But I’ve also started regularly listening to Sinéad Gleeson’s The Book Show and Castaway’s Bookish, hosted by the owners of two Irish bookshops. These two definitely have struck a chord with me because I’ve been reading so much Irish fiction. The country does seem to be going through something of a renaissance producing a profuse amount of writing of sterling quality. This has been debated about in the media such as this Irish Times article about a Guardian article which highlighted the “new Irish literary boom.” Although, to my mind, the best Irish book of the year is Mrs Engels which seems strangely missing from all these lists.

If you have favourite book podcasts please do comment and let me know about them as I enjoy finding more.

Finally, here are my top ten books of the year which have all made such a strong impact on me and left me thinking about them long after finishing the last page. Click on each title's name to read my full thoughts about these books.

A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James

It’s funny looking back on this post I made last year about books I wanted to read and hadn’t yet got to (including this one). At that point, Marlon James’ most recent novel had received praise from critics, but hadn’t made many sales. I didn’t get to reading it until this summer as part of judging the Green Carnation Prize. It went on to win as well as taking that obscure award called the Booker. What a difference a year can make in the life of a book!

The Green Road by Anne Enright

I felt slightly suspicious starting this novel because I was worried it wouldn’t do anything new, but Enright proves again with this novel that she's an enormously creative writer. She creates a fresh structure for this book and takes her characters into territories unlike any of her other tremendous novels. It all works to present a complex and entirely new kind of portrait of a family.

Mrs Engels by Gavin McCrea

Lizzie is headstrong and tough, but she possesses rare passion which bleeds through every page of this beautiful novel. It pierced my heart and stayed with me like nothing else I’ve read this year. Sometimes it's like I can still feel her near me with all her earnest judgement, wisdom, humour and tender feeling. I'm deeply saddened she isn't a part of my life any more.

Lila by Marilynne Robinson

I wasn’t expecting to like this novel much since I’d only felt a mild response to Robinson’s writing in the past. To my delight, it gripped me and held me all the way through. Lila is a girl who came from nothing but through the generosity of a scant few people and her own determination she makes a life for herself and finds a rare kind of love. This is writing which is profoundly moving and it’s a story which completely captured my imagination.

Almost Famous Women by Megan Mayhew Bergman

History books are strewn with footnotes about fascinating women like Lizzie Burns in "Mrs Engels" who probably never became more famous because of the simple fact that they were women or from a lower class. Bergman honours a select and fascinating few to create mesmerizing short stories with immense emotional depth. The points of view they pose allow us to re-enter history and question what we find there.

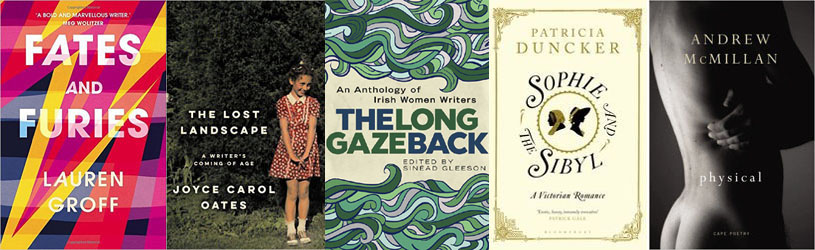

Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff

I was introduced to Groff’s writing last year when I read her impactful story in the Best American Short Stories 2014. What a thrill it was to discover that her compressed and strong style of writing can also work in such a long novel. This book was an absolute pleasure to read giving such a unique perspective on relationships and the secrets we keep from those closest to us.

The Lost Landscape by Joyce Carol Oates

It’s so rare for Oates to reflect on her own life in her writing. It’s unsurprising that she approaches the subject of childhood and her formative years in a deeply questioning and philosophical manner. In this creative and deeply-personal book she reflectively looks at her own life and her life as a writer/reader to produce a profoundly surprising point of view about the nature of identity.

The Long Gaze Back edited by Sinéad Gleeson

Many anthologies of short stories are a patchwork of good and fair stories, but few contain great after great like this revelatory volume of Irish women writers. Several stories are by writers whose books I've read and admired over the past couple of years such as Anne Enright, Mary Costello, Eimear McBride and Belinda McKeon. Other writers like Kate O'Brien, Maeve Brennan, Molly McCloskey and Anakana Schofield are new to me. There are stories of high drama and stories of subtle power, but all utilise language to capture exactly what it is they need to say. In addition to the fascinating diversity of styles and subject matters covered in this entertaining and lovingly-assembled anthology this book serves as a fantastic jumping off point for reading more of these talented writers' work which I'm now eager to track down. Each story is prefaced by compelling short bios for each writer which serve as helpful prompts for discovering more. This is a book to always keep by your bedside.

Sophie and the Sybil by Patricia Duncker

It’s rare that I find a book where I love every minute of the reading experience. This novel which functions as both a love letter and critique of George Eliot is tremendously fun, immensely clever and makes a truly romantic story. It takes a lot of bravado for an author to insert herself into a narrative, but Duncker does so with fantastic results.

Physical by Andrew McMillan

Poetry can be such an intimidating form of writing to engage with because much of it can feel opaque. McMillan’s extraordinary writing spoke directly to me. I’ve found myself going back to several poems in this book again and again. I’ve also recommended this book to a huge amount of people because I think these revelatory poems will connect with many.

Have you read any of these or are you now curious to give them a try? I've enjoyed reading through many end of year book lists so please comment to let me know your own favourites.