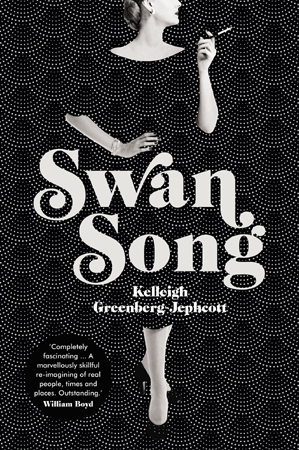

Daisy Johnson's debut book of short stories 'Fen' was a bewitching example of how modern-day real-world issues could be given a darkly imaginative fairy tale spin. So I've been greatly anticipating her debut novel which references both 'Hansel and Gretel' and the myth of Oedipus. Before reading it I went to see Johnson speak at a Waterstones event focused on modern reimaginings of myths (since it's a literary trope so in vogue at the moment given recent novels from writers such as Kamila Shamsie, Madeline Miller and Colm Toibin.) It was a relief to hear Johnson explain that she wrote “Everything Under” in such a way that no knowledge of the Oedipus myth is necessary to understand this new novel since my only familiarity with Sophocles' tragedy is mainly through the complex made famous by Freud. Nor have I read the original fairy tale of 'Hansel and Gretel' since I was very young.

So I went into reading this novel focusing purely on the story itself rather than how it relates to these classic tales. I wasn't disappointed because I'm so drawn to the universal themes she writes about, her characters who are outsiders on the margins of society and her strikingly distinct writing style. The beginning is so powerful in how it beautifully describes the sense of how we are tied to a sense of home which has forgotten us. However, I was quite confused throughout sections of this novel which jump through large periods of time and between characters. The story involves adoptions, gender fluidity, the disorientating effects of dementia and an elusive mysterious river monster named 'The Bonak'. But, by the end of the novel, I was fully engrossed and moved by how the pieces of the story slid together to form an impactful conclusion. It's the sort of book which I know will benefit from a rereading now that I understand its characters/plot better and the classic myths which were reworked into its structure.

A character named Gretel is at the centre of the story which primarily focuses on her quest to understand the past she's consciously forgot and find her mother Sarah who she's been estranged from for many years. The reason for Johnson's jigsaw style of storytelling seems to be rooted in a belief of how memories are necessarily distorted and also on a philosophy of life which is asserted by a character named Charlie. He claims that “life is sort of a spinning thing. Like a planet or a moon going round a planet… Sometimes it’s facing one direction but only for a second and then it’s spinning and spinning, revolving on its base so fast it’s impossible to really see. Except sometimes you catch a glimpse and you sit there and you know that’s what it would have been like if things had gone differently, that is the way it could have been.” Her characters can clearly envision different paths for their lives but find themselves curiously fated to follow trajectories that lead to dissolution and loneliness because of the bodies, families and circumstances they are born into. They are fettered by the past rather than liberated by a deeper understanding of it: “The past was not a thread trailing behind us but an anchor.”

It's interesting how Gretel's profession as a lexicographer seems to be a reaction against the instability of her upbringing where she and Sarah were so isolated they created a language for themselves: “They cut themselves off from the world linguistically as well as physically. They were a species of their own.” It's a compelling example of the way groups of people continuously splinter off from society, form cultures of their own and fold back into larger civilization to better inform and transform it. Just like time and language, gender and sexuality are never constant things in this novel. I really appreciated the complex way Johnson shows how her characters feel their way into inhabiting their bodies and expressing who they really are. Unlike most coming of age stories, there's a dark-edged violence to the anticipation of sex for Gretel when her mother Sarah gives a condom demonstration using a knife which tears through the material. Johnson excels at creating disturbing and tantalizing imagery which shakes the reader out of a complacent understanding of the world and this novel is a wondrous black gem of a book.