One the best things about blogging are the wonderful book recommendations I get from other readers and authors. Author Vestal McIntyre recommended I read Neel Mukherjee’s recent novel which I loved and reviewed. In turn, Neel recommended I read this short novel by Tiffany Murray and I loved it. A good eerie ghost story is a thrilling experience. Best savoured late at night when the house creaks and wind whistles outside heightening the atmosphere. The reader’s imagination hums with a sense of dread and the excitement of the forbidden. It’s like daring yourself to look under the bed or out of the window when all you can see in the dark glass is your own ghostly image reflected back at you. Tiffany Murray has created an innovative, thrilling tale worthy of the genre set in a stately English country house in the 1950s. Adolescent boy Dieter has inherited the enormous mansion as he is the only surviving Sugar of a long family line that has inhabited the Hall for hundreds of years. After his father’s tragic death the young boy moves into the dilapidated mansion with his German-born mother Lilia and his older half-sister Saskia. The family is poor and Lilia slowly sells off the contents of Sugar Hall so that they can sustain themselves. Meanwhile, lonesome Dieter happens upon a mysterious boy who engages him to play. Helpful neighbours including handyman John and well-born Juniper try to assist them into adjusting to the old fashioned lifestyle of being the proprietors of a great Hall. But threatening, creepy events make life uneasy for the family. They are unwittingly engaged in a tragic story that has haunted Sugar Hall for a long time.

This book is all about atmosphere and Murray is highly adept at making the air hum with tension through her precise prose style. One clever thing she does to introduce you to the hall is present a scene where Saskia is idling around the house singing. She is overheard by both Dieter and Lilia in other parts of the house. So while you read about their particular points of view you are also aware of Saskia lingering in the background and Dieter and Lilia’s humorous perspectives on her singing ability. By presenting these different perspectives on a single incident it creates a kind of three-dimensionality in the reader’s imagination so it’s possible to spatially visualize a scene. It’s actually a technique Mukherjee skilfully employs at the beginning of his novel “The Lives of Others” as well.

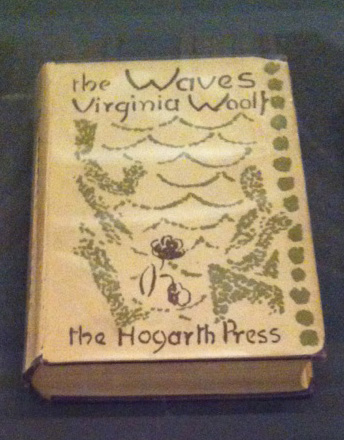

Each chapter in “Sugar Hall” is preceded by images such as illustrations of moths (which are rife throughout the great house) or letters. This lends an air of authenticity to the text like a trail of clues leading you gradually to discover what’s really going on. Murray’s descriptive use of colours makes Sugar Hall come vividly alive. Many rooms in the stately home are colour coded in an edgy, intimidating way. For instance the library is a “garish red” which certainly doesn’t make a relaxing, contemplative environment for reading. In fact, each room seems to be super-saturated with a certain colour making for an odd, unsettling place to inhabit. My only tiny qualm is the one instance where Murray describes something as “lemon yellow.” I believe the past three novels I’ve read have all used this synesthesia-like combination and, to me, it feels like a sort of creative writing school staple which grates slightly rather than creating the sense association that is intended. Otherwise, the writing and rich descriptive phrases Murray creates feel wholly original.

Striking images populate the novel which created a lasting impression in my imagination. For instance, early on Dieter shows a fascination with certain words like glamour. He uses some of his mother’s lipstick to colour his lips and practices saying the word in the mirror. I’m not sure how deeply Murray intended the use of this word, but the etymology of the word glamour is that it is an alteration of the word grammar. It’s a meaningful association here as the boy Dieter encounters cannot speak at first. Grammar also derives from the Latin word grammatica which was used in the Middle Ages in association with scholarship of occult practices. Thus Dieter’s fascination with the word might act as a kind of talisman to summon unruly spirits. Of course, trying to read deeper into these things isn’t necessary to enjoy the original and memorable images that Murray creates.

Murray is also skilled at creating moments of high intimacy/sensuality. I don’t mean sexual necessarily. There is a physicality in the narrative which made me feel present and wholly in the moment. For instance, at one point John explains to the boy Dieter he has bad lungs and he invites the boy to listen to the rattle in his chest. In another scene Dieter cuts his finger and the boy he plays with takes the finger in his mouth to suck. Later Lilia goes swimming in a river and feels such a keen sense of liberation floating in the water out in the open. In a number of scenes like these I felt so present in the moment it was like I was experiencing the characters’ tangible reality.

Lilia sings the song "Hänschen klein" to herself

The children really dominate the story in the beginning of the book: curious-natured Dieter with his longing to rejoin the gang of kids he belonged to in London and flighty Saskia who tries to affect a posh voice, idolizes the murderess Ruth Ellis and longs to become an actress. But it’s Lilia and her complex back story which really develops as the novel proceeds. There are also some marginal characters which are equally as compelling. In particular there is a wonderfully distasteful and crotchety vicar named Ambrose who keeps a moth collection. He and his wife are described as having such an intense mutual contempt for each other I could imagine them having an anguished and tortured novel of their own.

The story takes place in a time period where the deprivation and destruction that came from recent WWII is still being felt. The Hall represents a fading monument of privilege and the breakdown of colonialism. The lingering sin of long-abolished slavery demands recompense. These larger issues loom in the background, but really this is a story of a haunting that is handled with great delicacy and tact. In ghost stories time fluctuates, becomes circuitous and twisted. So the characters here are wrenched out of this particular point in the 50s. Their lively existence is turned to husks as dry and dead as pinned moths when confronted with the infinite echo chamber of the past found in Sugar Hall. This story is a thrill for the senses and an excellent read.