Reading a long epic novel by Oates is a wholly immersive experience. I became fully lost in this book, grew to love the uniquely individual characters and spent a lot of time contemplating the intellectual and emotional conundrums that the author presents. It’s a dramatic, extraordinary story that explores large subjects like the Iraq war, the American penitentiary system, alcoholism and spousal abuse. Yet, the main thrust of the tale is a deeply personal story of a family that’s been splintered apart and slowly draws itself back together to form anew. In the fictional town of Carthage, a small community in upstate New York, a young college-aged woman named Cressida goes missing. Her respected ex-mayor father Zeno desperately tries to find her. A war-veteran named Brett who is the fiancé of Cressida’s sister is suspected of being involved. Like the drawings of M.C. Escher (whose art Cressida has an intense passion for) the laws of logic/gravity are suspended as the family desperately tries to find out what happened to their youngest daughter and are forced to go around in endless circles while the search is conducted. Time becomes distorted for them “time passed with dazzling swiftness even as, perversely, time passed with excruciating slowness.” This description so perfectly encapsulates the feeling of life in a time of crisis. The truth of Cressida’s fate is surprising and heartbreaking. Over the course of the artfully composed narrative we learn what happens to her and the other compelling characters involved.

The novel takes time with each of the characters allowing us to understand them along their own personal journeys. But Cressida is always at the centre of the novel and she’s someone I grew to love although she initially comes across as an abrasive and difficult individual. As a precocious and passionate person she doesn’t easily reveal herself. With a teenager’s typical cynical attitude it was “easier for Cressida to mock than to admire. Easier for Cressida to detach herself from others, than to attempt to attach herself.” However, when she does show passion for a cause or individual she puts herself wholly into them. When she’s rebuffed or misunderstood she retreats and becomes very bitter and more carefully guarded as a result. She attempts to create her “self” anew. But the veneer of a new identity can only last for so long. “She’d cobbled together a self, out of fragments, she’d glued and pasted and tacked and taped, and this self had managed to prevail for quite a long time. But now… she was falling apart.” The attempt to adapt and create oneself is a necessary method of survival; as the world changes we must change with it. But eventually the past impinges upon the present and you can no longer deny who you really are. When Cressida fully realizes this she must take drastic action.

Apart from the focal point of Cressida, we encounter a fascinating array of characters driven by their own individual logic. Her mother Arlette whose husband dismisses her worries saying that she tends to “catastrophize” things finds great personal faith and strength in the face of tragedy where many others would crumble. Touchingly she must find places to cry in secret away from camera and members of the community during the search for her daughter. Her husband Zeno follows a diametrically opposite downward trajectory. Where once this intelligent well-meaning man was strong he becomes inconsolable, resorts to drinking and longs for the return of what was once a loving stable family unit. As Oates writes: “It is a terrible thing how swiftly a man’s strength can drain from him, like his pride” The shock of losing his daughter so swiftly and not being able to rectify the situation renders him powerless and causes him to lose all his confidence.

Aside from the family one of the most intriguing and virtuous characters in the book is the mysterious figure of the “Investigator.” This is a journalist who has written a series of books which expose corruption and the American institutional exploitation of the lower classes. Like a literary version of the scrupulous documentary filmmaker Fred Wiseman the “Investigator” bears witness to systematic corruption and complex systems which cause the downtrodden to remain underfoot. However, Oates sensitively portrays that devotion to a larger cause means great personal sacrifice is needed leading him to be emotionally closed to others. Another fascinating character is a strong-willed lesbian named Haley McSwain. Essentially she is a person led by good morals, but who has been embittered by experience with the world which leads her to take questionable actions. The pain she carries from her past hurt is so palpably real she arrives in the course of the narrative as a fully-realized human being who makes a powerful impact.

Oates uses multiple perspectives and narrative techniques to fully map the dramatic events she lays out. The reader inhabits the perspective of naïve young soldier Brett who has been sent to fight in Iraq. “Following orders you forget what was the day before… Sand inhaled in lungs so each breath you took, you drew the desert deeper into you.” The confusion and sense of dislocation carries through following his return to the United States. Memories flash through and mingle with the present showing how neurological damage caused in battle has impacted his consciousness. We also hear the breathless voice of his fiancé Juliet who tries desperately to assist Brett in his rehabilitation and assimilation back into American life. There are impersonal journalistic accounts of crime conducted during wartime paired with crime in an average American community during peacetime. Sometimes text is blacked out like documents that have been censored. Other times general opinions are delivered by a single individual such as when Brett’s friend gives a conversational account of Brett’s character where the text is marked as italicized. The narrative voice switches between these different levels of interiority and objectivity to give a rounded picture of events. Through this skilful technique Oates allows us to understand the characters’ thoughts, the general perspective of the community around them and the characters’ reactions to those popular attitudes.

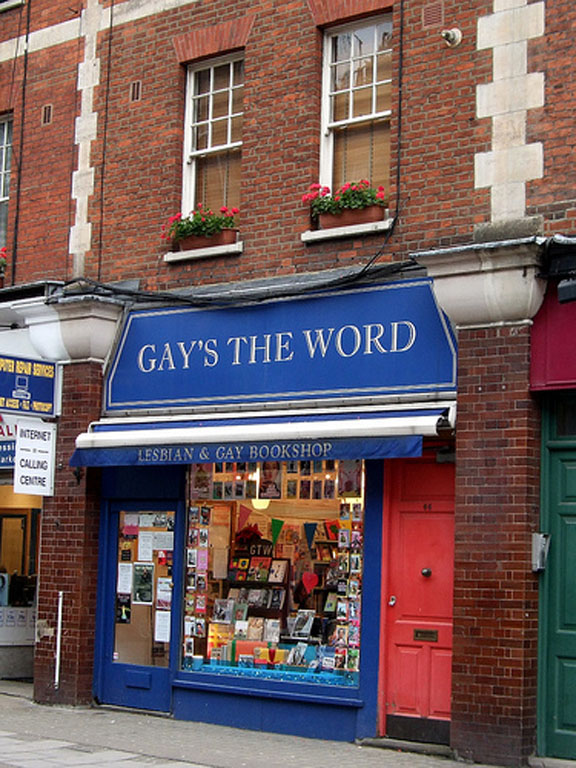

'Ascending and Descending' by M.C. Escher

Amidst this engrossing story Oates presents a number of philosophical dilemmas. For example, we are prompted to question the meaning of home. The question presented “Why is it, when you dream about a place meant to be ‘home’ –or any ‘familiar’ place –it never looks like anything you’d ever seen before?” Notions of “home” are inextricably linked with nostalgia and idealism so the physical reality of the place in which we were raised and nurtured resides in an emotionally-coloured compartment of the mind. The interplay between the tangible “home” and the imagined “home” feed into how we construct our sense of “self” – another concept which is scrupulously questioned and explored throughout the story as I already discussed concerning Cressida’s character. Alongside these issues which centre around the essential meaning of “personality” are issues of broader social inquiry such as ‘what is good?’ and ‘what is ethical?’ Approaches to answering these questions are drawn on both religious and atheist viewpoints as filtered through the characters’ perspectives. These profound questions are skilfully intertwined with the story being told so that you often don’t realize you’re pondering them till later when thinking about the mental journey you’ve just taken.

The heft of the subjects involved in this novel are tempered at times with humour – most of which involves intellectually playful commentary on the human condition. For instance, Cressida with her sly sensibility at one point paraphrases a remark by W.H. Auden: “We’re here on earth to help other people. But what the other people are here for, nobody knows.” At another time when Zeno is confronted by his daughter who asks why he didn’t carry on producing offspring in order to also have a son he wryly explains “I’ve been spared little Oedipus eyeing me out of the shadows.” Sometimes the joke is more subtle such as when Oates comments on the implausible expectations of reciprocal affection: “Always you believe that those whom you adore will adore you. Not in any species other than Homo sapiens is this possible- this delusion!” The wit shown with remarks like this demonstrates how it’s important to maintain a sense of life’s inherent absurdity even while mired in the multifarious difficulties it presents.

Carthage manages to both highlight contemporary issues at the centre of American life today and also create a distinctly localized tale of loss, heartache and redemption. A tour through a prison is described in such realistic and striking detail I felt as if I had actually walked through the prison myself. It’s with such vividly descriptive power that I feel transformed by the novel I’m reading so that I’m more aware of the world and have a more dynamic way of processing it. This is the kind of book that reminds me how potent storytelling can be. It’s an impressive accomplishment.