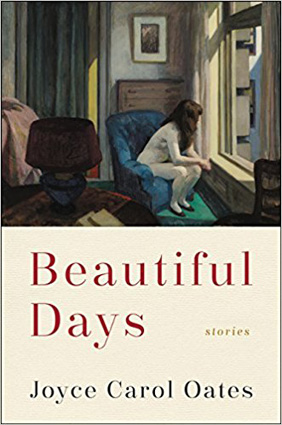

For all the daring stylistic variations and rich diversity of subject matter found in Beautiful Days, Joyce Carol Oates’s latest collection of short stories, there is a common theme throughout of disruptively close encounters with the “other.” At the Key West Literary Seminar in 2012, Oates gave a talk titled ‘Close Encounters with the Other’ and in this session she describes how “There comes a time in our lives when we realize that other people are not projections of ourselves - that we can’t really identify with them. We might sympathize or empathize with them, but we can’t really know them fully. They are other and they are opaque.” So in these stories characters strive for connections which often tragically break down. These encounters document the awkward or sometimes violent clashes that occur between individuals who are so dissimilar there is an unbreachable rupture in understanding. The factors that divide these characters include issues such as romantic intention, gender, age, race, class, education and nationality. Oates creates a wide array of situations and richly complex characters to show the intense drama that arises from clashes surrounding these subjects.

Some stories take fascinatingly different angles on the question of trust and the durability of love within romantic affairs or long-term marriages. In ‘Fleuve Bleu’ two married individuals initiate an affair with a declaration that they will maintain complete honesty. Yet there are fundamental issues left unsaid which motivate one individual to abruptly bring their affair to a halt. Here descriptions of the environment strikingly emote the passion of their connection and erotic encounters. A couple at cross-purposes is also portrayed in 'Big Burnt' where a weekend tryst to an island is initiated because Lisbeth wants to make Mikael love her, but Mikael wants a woman to witness his suicide. Whereas in 'The Bereaved' it feels as if the female protagonist was taken on as a wife only to care for the husband’s motherless child. The child’s early death precipitates a feeling of her role being taken away as well as deep feelings of guilt which manifest in a fascinatingly dramatic way while the couple embark on an ecological cruise. The stories suggest that no matter the passion or fervour of a couple’s connection there is an element of unknowability about one’s partner which makes itself known in the course of time.

Other stories describe class and racial conflicts between teachers and pupils. In 'Except You Bless Me' a Detroit English teacher named Helen earnestly tries to tutor her pupil Larissa despite strongly suspecting this student is leaving her aggressively racist messages. This is an interesting variation from a section of Oates's novel Marya where the protagonist encounters slyly aggressive behaviour from black janitor Sylvester at the school where she teaches. Both are expressions of the quandary a white individual might have faced at this time of Detroit history when racial tensions ran high. Helen makes little progress in her tutoring and then, many years later, finds herself in a vulnerable position with a woman she imagines to be Larissa as an adult. Like in 'The Bereaved', the protagonist is somewhat aware of her own prejudices, but is nevertheless drawn into paranoid fantasies. However, the wife of 'The Bereaved' is prejudiced not about race, but the obesity and perceived stupidity of a family aboard the cruise ship. Fascinatingly, she thinks of this family as like people who might be photographed by Diane Arbus in contrast to other groups on the ship who are like “Norman Rockwell families”. The central characters in these stories turn certain people they encounter into antagonists because there is an “otherness” about them which they can’t overcome.

Intergenerational conflicts which are described in some other stories are centred around a parent/child relationship. In 'Owl Eyes' teenager Jerald appears to have some form of autism where he has very advanced abilities in mathematics and experiences feelings of panic when there are deviations from his fixed routines. He regularly travels to a university campus to attend a calculus class, but when a man approaches him claiming to be his estranged father Jerald can’t reconcile how this man might fit into the narrative created by his single mother. Jerald is reluctant to engage with memory because, unlike math, it is uncertain and has an inherent malleability: “Memories return in waves, overwhelming. You can drown in memories.” Memory is distorted in the tremendously ambitious story 'Fractal' which is also about a mother and her son. At the beginning of this story the characters are only referred to as “the mother” and “the child” as if these identity roles supersede any individuality that would grant them names. “The mother” indulges her child’s specialist interest by taking him to a (fictional) Fractal Museum in Portland, Maine. As the pair explore the museums exhibits, multiple versions of their reality are gradually introduced until “the mother” is confronted with a true past that she’s wholly denied.

A very different kind of teacher/pupil relationship is depicted in 'The Quiet Car' where an arrogant male teacher/writer reflects on his declining literary fame and an adoring female student who he viewed in a disparaging way. When he bumps into this student again many years later he’s confronted by how his conception of himself has been overly inflated. Oates has recently shown a particular knack for excoriating the pompous egos of celebrated male authors/artists in her fiction. Most notably this can be seen in her collection Wild Nights! and her controversial depiction of Robert Frost in the short story ‘Lovely, Dark Deep’. However, Oates constructs a more playful tribute to a particular author’s ambition and his lasting impact in her story 'Donald Barthelme Saved From Oblivion'. Here she memorably describes the writing process as like walking over and over across a high wire and makes acute observations about the meaning and endurance of art.

The vivid and intense story 'Les Beaux Jours' contains a much sharper critique of the problematic nature of artist Balthus’s famous painting. Here the reader inhabits the troubled psyche of the girl depicted in this artwork who is like an enslaved fairy tale heroine while simultaneously existing as a girl from a broken affluent NYC home. As with many stories in the second section of this collection, this story slides into the surreal as does the brief and powerfully haunting story ‘The Memorial Field at Hazard, Minnesota’. Here the author’s condemnation for the tyrannical nature of ego-driven politicians sees a former president forcibly condemned to the hellish task of digging up graves of those who were victims of his poor policies and warmongering.

Oates creatively engages with the politics of immigration in what is probably the most radical story in this collection 'Undocumented Alien'. Here a Nigerian-born young man J.S. Maada enters into a secret governmental psychological experiment rather than face deportation. A chip planted in his brain causes a “radical destabilization of temporal and spatial functions of cognition” and results in him believing that he’s an agent from planet Jupiter's moon Ganymede. This leads to paranoid fantasies and a horrific confrontation with the white lady who employs him as a gardener. It’s tremendously poignant that the way J.S. Maada is manipulated, persecuted and discarded is indicative of how an intolerant section of white America reacts to “otherness.”

This collection of stories seems to possess an urgency and anger influenced by current American politics. It never ceases to amaze me how Oates continually pushes boundaries and orchestrates a dialogue around some of the most pressing matters in society today. In addition to how these stories address many dramatic instances of confrontations with the “other”, they also possess an impressive diversity in their style and form. The bold variety of narratives in this collection continuously surprise and delight. Much of the fiction in Beautiful Days is longer than a typical short story. With several stories tipping into lengths considered to be a novella, it feels that many could easily expand out into novels. Given that Oates’s forthcoming novel (currently titled) My Life as a Rat is based off her short story ‘Curly Red’, it will be interesting to see if the author chooses to build upon any of the short fiction in Beautiful Days. However, the stories in this collection stand firmly on their own with all their startling psychological insight and bracing depictions of tragic conflict.

This review also appeared on Bearing Witness: Joyce Carol Oates Studies