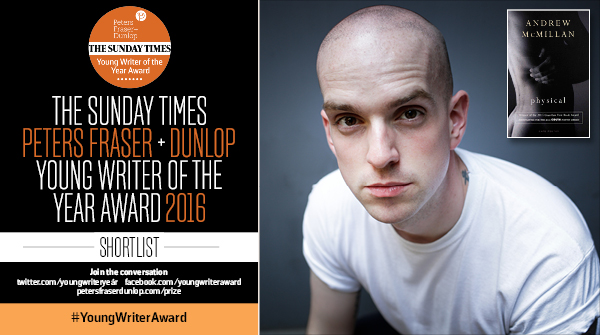

As a final post about the Sunday Times/Peter Fraser & Dunlop Young Writer of the Year award, here is Naomi’s review of Porter’s book. It was so interesting to hear Naomi talk about this at our shadow judges' meeting and reading her review since she knows Ted Hughes’ Crow so well and I’ve never read it. Nevertheless, I think this is an extraordinarily book that I also loved and you can read my review about it here. It's been a pleasure featuring Naomi's reviews here. Read more of her writing at TheWritesofWomen!

I’m going to set my stall out from the first sentence: Grief Is the Thing with Feathers is an extraordinary piece of work. Porter creates a scenario in which a woman has died suddenly leaving her husband – a Ted Hughes scholar – and their two young boys behind. Into their grief-stricken word arrives Crow, the Crow from Hughes’ collection of the same name, who rings the doorbell of their London flat a few days after her death.

One shiny jet-black eye as big as my face, blinking slowly, in a leathery wrinkled socket, bulging out from a football-sized testicle.

SHHHHHHHHHHHHH.

shhhhhhhh.

And this is what he said:

I won’t leave you until you don’t need me any more.

The grief the characters go through is narrated by three voices: Dad who attempts to go to work, write a book on Hughes’ Crow and parent his children; Boys who speak as one voice and wonder what happened to the fire engines and the chaos that they feel should’ve been present at the death of their mother, and Crow who is slippery – is he the father’s therapist? A trickster? A myth? A bird feeding on grief?

There is no plot as such. Porter moves the characters forward as though they’re in fog or a timeless bubble. Things happen but grief colours almost all of their movements as they try to negotiate a world without a wife and mother. There are heart-breaking moments when Porter articulates how that grief feels without becoming mawkish.

Ill people, in their last day on Earth, do not leave notes stuck to bottles of red wine saying ‘OH NO YOU DON’T COCK-CHEEK’. She was busy not dying, and there is no detritus of care, she was simply busy living, and then she was gone.

She won’t ever use (make-up, turmeric, hairbrush, thesaurus).

She will never finish (Patricia Highsmith novel, peanut butter, lip balm).

And I will never shop for green Virago Classics for her birthday.

I will stop finding her hairs.

I will stop hearing her breath.

But there’s humour too. Crow is arrogant, obnoxious and sometimes cruel but he’s also very funny. The first time Dad brings a woman home and has sex with her, he finds Crow on the sofa ‘impersonating me pumping and groaning’. He also likes to show off in the bathroom, ‘performing some unbound crow stuff’ for Dad to believe he’s ‘hearing the bird spirit’

Gormin’ere, worrying horrid. Hello elair, krip krap krip krap who’s that lazurusting beans of my cut-out? Let me buck flap snutch clat tapa one tapa two, motherless children in my trap, in my apse, in separate stocks for boiling, Enunciate it, rolling and turning it, sadget lips and burning it. Ooh, pressure! Must rehearse, must cuss less. The nobility of nature, haha krah haha krap haha, better not.

Reviewers seem to have struggled with how to describe the form of the book; is it prose? Is it poetry? Is it a prose poem? I think that the form Porter’s chosen to take is one that suits the subject matter. Grief is impossible to define accurately. It ebbs and flows, visiting each of us differently. Porter’s words appear to be divided into phrases, sentences and paragraphs as he felt they should be as opposed to him attempting to force them into a standard or accepted format. That and the language he uses – which moves between Standard English and invented words – helps to portray a family out of sorts and an animal from literature which may be a figment of the father’s imagination.

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers is extraordinary for several reasons: the form and language; the vivid imagery; the integration of Hughes’ Crow (although you don’t need to know Crow in order to appreciate this work); the depiction of grief. Max Porter’s a very exciting young writer indeed.