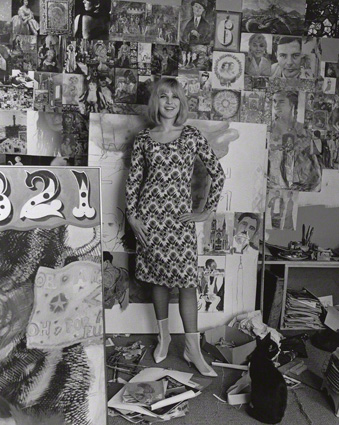

“Swing Time” is being published this month, but I first read it in July because I had the great honour of being invited to interview Zadie Smith at this wonderful preview event. Having been a long time fan of Smith’s writing, it’s so interesting to see how this new novel differs from her other books in some ways but also develops further some of her most prevalent themes. Many of her novels give equal time and focus to several characters, yet “Swing Time” is written entirely from the perspective of a single nameless narrator. This gives the novel a more nostalgic feel because it vividly recounts an adolescent girl coming of age during the 1980s in North London. She befriends an energetic girl named Tracey (because their skin colour is similar) who claims her absent father is a backup dancer for Michael Jackson. The girls develop a love of dancing in a class and through watching scenes from Old Hollywood musicals that often involve Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers or semi-obscure African American actress Jeni LeGon. The novel follows the gradual breakup of their friendship and the narrator’s early adulthood when she works as a personal assistant for a famous pop star who wants to found a school for girls in West Africa. Eventually these two aspects of the story weave together showing how the narrator arrives at a crisis point. It’s an extremely engaging and intelligent novel about friendship, racial identity and our perception of time.

Central to the narrator's life are three strong-minded, wilful and (some might say) difficult women: friend Tracey, the narrator’s (nameless) feminist mother and the pop star Aimee. Tracey is a wilful girl who often leads the narrator and their friends into delinquent behaviour. It’s easy relating how as an adolescent you would be easily drawn to but secretly repulsed by her behaviour. It’s also touching the way Smith relates how at that age you overlook obvious lies that friends sometimes tell you so as not to embarrass them. There are also startling scenes involving abusive sexual behaviour from schoolboys towards the girls at their school. Smith delicately handles how the girls were not simply victims to this outrageous behaviour, but in some cases participated in it. This definitely doesn’t excuse the behaviour of the boys, but shows the complexity of burgeoning sexuality. It’s also skilfully presented how their friendship ebbs and flows until a point at which the girls’ paths in life sharply split apart.

The narrator’s mother (who also remains nameless) is an absolutely fascinating individual. She's one of those characters I find utterly compelling to read about, but I'd be terrified of meeting her in real life because she can verbally cut people to shreds and often does. She has an impatient attitude towards all the usual domestic duties and interests that other women (such as Tracey’s mother) on the council estate engage in. Instead she spends as much time as possible reading, educating herself and developing social projects such as a hilariously disastrous scene where she tries to turn a square of grass on the estate into a community garden for local children. As well as being fiercely driven and community minded (even when it goes against the opinions of those around her) she has a touching vulnerable side which comes out especially when her partner’s children from a previous marriage arrive at their apartment one day.

Finally, Aimee is an American mega pop star who first rose to fame in the 80s. She’s a white singer and a great dancer whose image has evolved through decades of continuing popularity with a strong gay fan base and a keen interest in philanthropy work in Africa – any guesses who she might be partly inspired by? Through a quirk of fate when the narrator works at a music company she ends up becoming Aimee’s personal assistant. The pop star operates on some other level of reality where she wants to magnanimously found a school for girls in an impoverished part of Africa, but doesn’t want to involve herself in the complexities of local politics. Yet, being mixed race the narrator finds her time in Africa and the connections she makes with some people there has a profoundly personal affect upon her. It’s also her entanglements with some of these people that put her working relationship with Aimee in jeopardy.

At the centre of the novel are the very personal and thoughtful observations of the narrator who we get to know intimately (even though we never learn her name). She has an interesting way of considering perceptions of identity and how she views herself by watching many old musicals and interacting with people in Africa. There’s a remove from experience whether its watching these films with their dodgy representations of black people or the teaspoons of truth she gets from her African friends: “great care was taken at all times to protect me from reality. They’d met people like me before. They knew how little reality we can take.” It’s moving the way she is searching throughout the novel to find reflections of herself and struggles to understand where she fits into society.