I’ve read and admired short fiction by Robert Olen Butler in the past so I was highly intrigued to read his new novel “Perfume River”. The story is centres around brothers Robert and Jimmy who have been separated for almost fifty years. When they were both young men they were pressured by their domineering pro-war father William to fight. Robert enlisted for a non-combat position to avoid causing any bloodshed himself, but he inevitably became entangled in conflict. Jimmy chose to move to Canada and pursue an open relationship within a commune. Ideological divisions have torn this family apart, but when elderly William is seriously injured in 2015 the family comes together again to lay old grievances to rest. This is an elegiac, thoughtful novel which shows the long-term deleterious effects war has upon families, the complex intensity of lifelong relationships and the real meaning of masculinity.

Hovering at the edges of this family drama is a homeless man named Bob. Robert occasionally buys him meals. He seems to suffer from a kind of schizophrenia and frequently has trouble separating his present reality from past emotionally damaging encounters he had with his aggressive father Calvin. Butler inhabits his skewed perspective of the world so powerfully – especially in the way Bob has an awareness of how he’s perceived by other people and their assumptions about him. Since Bob shares a name with the protagonist Robert there is a strange mirror effect which occurs between these men of different ages who have ended up in very different places in their lives. The tensions which play out in their psyches eventually reach a crisis point in a dramatic confrontation.

Robert’s wife Darla who teaches art theory engaged in antiwar protests during the Vietnam war arguing with her father that it’s naïve to think the country will become a “puppet state for the Chinese.” She met Robert during her demonstrations and she has since gone on to meditate on the meaning of military aggression and the pride men feel about engaging in acts of warfare. There are a lot of touching scenes where the couple’s close contact is described: “They are so very familiar with each other. And that familiarity has become the presiding expression of their intimacy.” Butler gets so well the special kind of energy and space created within a long-term relationship and how this expresses itself physically with contact taking on a curious kind of timidity. Their familiarity is such that communication is mostly non-verbal and there are multiple unspoken understandings between them. This is in contrast to Robert’s brother Jimmy and his partner Linda who have an open relationship because they believe “Love on this earth is not a singularity. It is a profusion.” The author explores the positive and negative aspects of these different approaches to long term relationships and meaningfully shows how no arrangement is ideal.

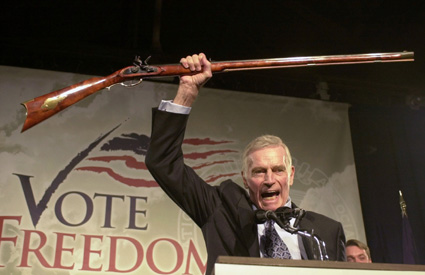

"Charlton Heston. Bob's old man loved this guy. Moses the gunslinger."

The close lifelong partnership Darla shares with Robert is haunted by the hidden truth about what he encountered in Vietnam – both a tragic incident that occurred and the woman he fell in love with. It’s movingly described how Robert tries to keep these memories to himself: “Robert blinds hard against the memory. He will not let certain things in.” Butler really has a special talent for writing about the way memories wash over people. Thoughts/feelings about the past meld into their present day lives in such a seamless organic way it really represents the way the present can be veiled by the past. This is metaphorically represented by the heavily scented river Robert encountered in Vietnam and how sensory experience triggers emotions in the mind taking an individual out of the present moment.

At the heart of this novel are questions about what forms our identities and to what degree we’re pledged to our family, friends or country. This long passage poignantly summarizes this debate: “your interests and tastes, ideas and values, personalities and character – the things that truly make up who you are – shift and change and disconnect. Indeed, it’s harder for friends to part: you came together at all only because those things were once compatible. With your kin, that compatibility may never even have existed. The same is true of a country. You didn’t choose your parents. You didn’t choose your land of birth. If you and they have nothing in common, if they have nothing to do with who you are now, if you are always, irrevocably at odds with each other, is it betrayal simply to leave family and country behind? No. Fuck no.” The consequences of this rallying statement about asserting the right to form your own identity apart from your roots is played out in Jimmy’s actions. But the novel contrasts how making such a radical decision involves compromises which are different from the ones made by Robert who chose to remain in his country and keep in close contact with their family.

“Perfume River” is such a beautifully written novel and movingly shows that there are no easy answers to these larger questions – particularly when it comes to acts of war between nations and between family members.