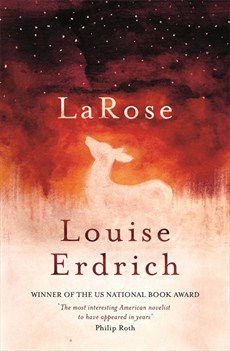

Louise Erdrich is one of those well regarded American authors I’ve always meant to read, but never got around to. When I was sent a copy of “LaRose” I thought I’d dip in to see what her writing style was like. The story had me instantly hooked! It begins with a terrible hunting accident within a Native American community. A man named Landreaux accidentally shoots his neighbour/friend Peter Ravich’s young boy. To compensate for the loss he’s caused and in keeping with his tribe’s tradition, he offers his equally young son LaRose to Peter and his wife Nola to compensate him for his loss. There follows an emotionally complex series of events as the Ravich family struggle with their real son’s loss and Landreaux’s family adjusts to living without LaRose. Meanwhile the boy is caught in the middle. This extraordinary drama raises questions about the meaning of family, guilt and the role traditional Native American beliefs, practices and history play in modern day life making this a deeply engaging novel.

Erdrich has a special ability for writing compelling three-dimensional characters who stick with you. Peter’s wife Nola is a strict Catholic and a hardened woman with self destructive tendencies. The way that she and her strong wilful teenage daughter Maggie play against each other is wholly believable. They are combative characters that find themselves united by love in moments of real crisis. At one point Nola looks at her daughter and realizes “She had raised a monster whom she hated with all the black oils of her heart but whom she also loved with a deadly confused despair.” This compellingly conflicted relationship plays out in a way which shows deep layers of hidden emotions.

The unorthodox Father Travis is a fascinating individual who formerly served in the military. He finds that “Getting blown up happened in an instant; getting put together took the rest of your life.” Now he takes an active role in recruiting converts by trawling bars to preach to the most vulnerable and running a drug/alcohol rehabilitation group. Romeo Putay lives on the margins of the community, skimming prescription drugs off from the sick and elderly to use or sell at a profit. He also hoards discarded information to later leverage a sense of power over those he believes have wronged him. The story of his difficult childhood and orphaned life alongside Landreaux is particularly memorable. Romeo’s son Hollis has been raised by his former friend Landreaux adding another dimension to the sense of improvised family units and loose support networks formed to bring together a suffering community.

The individuals living on the Native American reservation in Erdrich’s novel engage in a self conscious struggle with problems that affect their community. A friend of Landreaux’s teaches Ojibwe culture and “Going up against demons was Randall’s work. Loss, dislocation, disease, addiction, and just feeling like the tattered remnants of a people with a complex history. What was in that history? What sort of knowledge? Who had they been? What were they now? Why so much fucked-upness wherever you turned?” The overall portrait is of a people strengthened by their traditions, but hampered by years of being inhibited by institutions that have slighted them and a history of oppression. Romeo has a conversation in a bar with his son Hollis where the teenager remarks about their people “When we fuck up now, we mostly fuck up on our own” to which Romeo replies “Are you crazy! That’s called intergenerational trauma, my boy!” The common problems of their people can’t simply be changed by personal willpower because they are the result of many years of systematic abuse and a conscious effort to eradicate their culture.

Writer L. Frank Baum once wrote: "The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians."

Within the novel Erdrich recounts the shocking fact of author L. Frank Baum’s chequered journalist past where he advocated for the extermination of Native Americans. I had never heard of his outrageous assertions but subsequently read about it in this NPR article and in other sources. Erdrich also incorporates elements of Native American folklore into her story in the form of a particularly unsettling and surreal section about a teenager named Wolfred who flees with a girl who is sold into slavery by her own mother, but the pair are continuously followed by the head of Wolfred’s boss Mackinnon in a way which is terrifying. These fantastical elements add a layer to the novel’s underlying messages about issues to do with guilt and possession which saturate the entire culture.

Erdrich’s way of writing about tricky moral dilemmas and very sympathetic characters reminds me of the excellent Canadian writer Joan Barfoot. She looks at complex issues and tests how they play out in extreme situations. I hope to read more of Erdrich’s acclaimed work based on the strength of this novel. “LaRose” is an absorbing and utterly fascinating read.