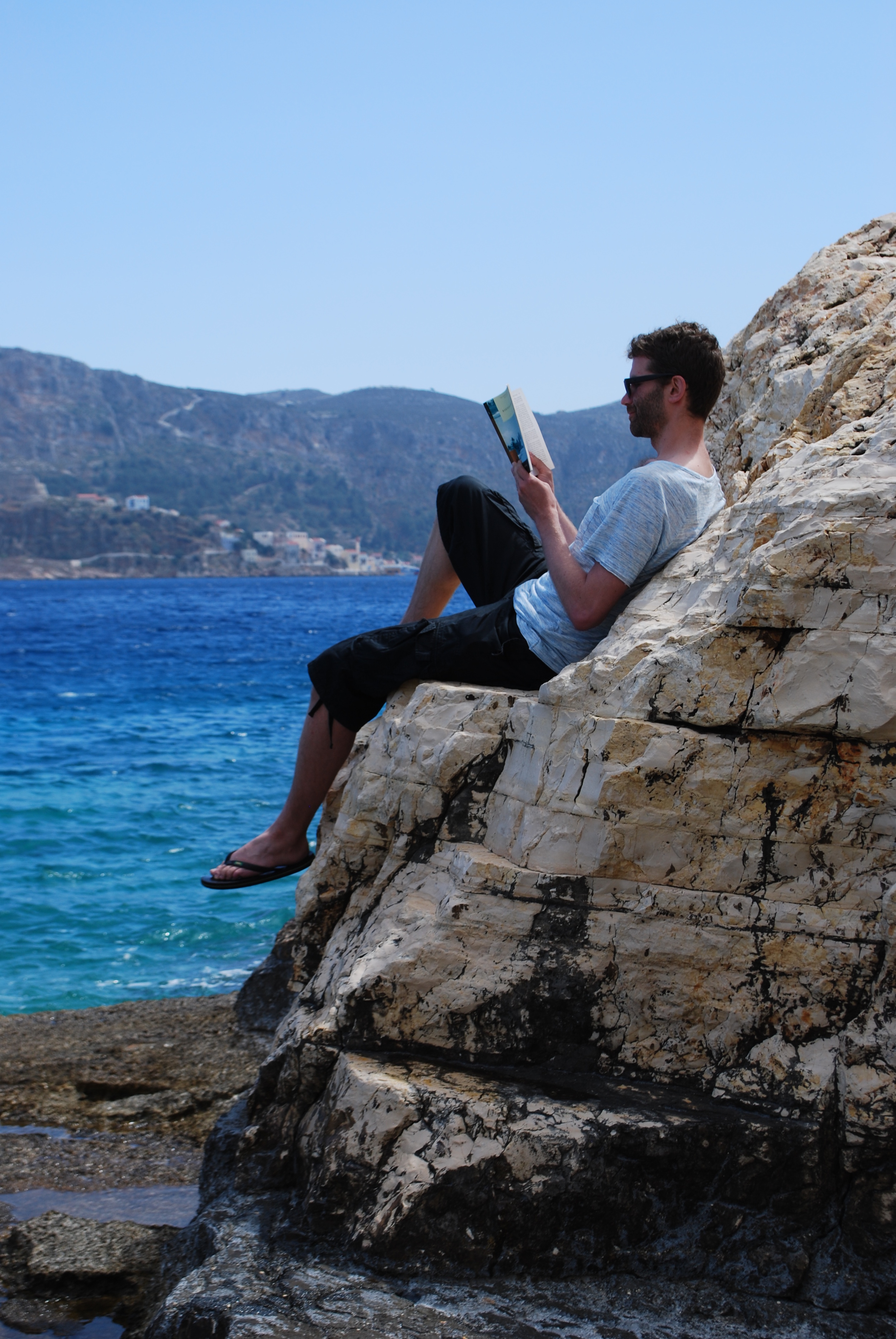

Recently I spent a week on Kastellorizo, a tiny Greek island in the Mediterranean that is only five square miles of rocky land populated mostly by goats. The primary bit is a small bay which has a cluster of hotels, restaurants and cafes near which you can sit at tables on the water’s edge to watch fish and turtles swimming by while drinking retsina and reading. It was a wonderful break and I really needed some quiet offline disconnected time. I think being liberated from the internet, email, twitter and phones is good for the soul sometimes. Since I work two jobs over six days a week, I can sometimes feel a bit overwhelmed. But I’m also aware how lucky and privileged I am to be able to go to such a peaceful, beautiful location.

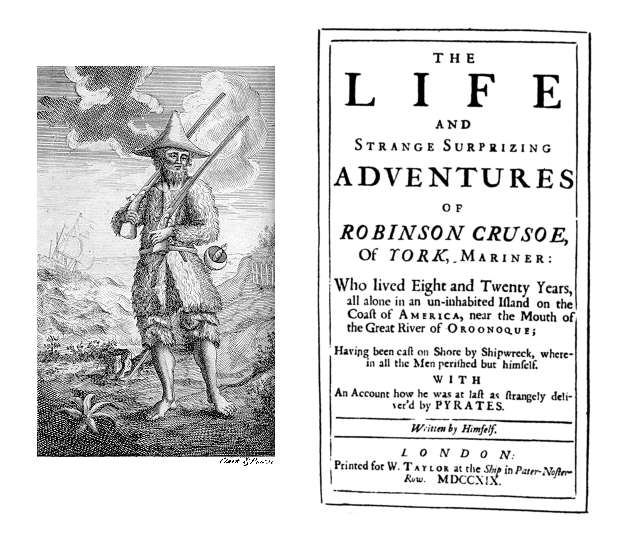

Since I was on an isolated island I thought I’d stay on theme with my reading and devour only island fiction. My first point of call had to be “Robinson Crusoe” which I had never read before and it’s my first time reading Daniel Defoe. I was expecting a tale which is part adventure and part meditative exercise about the state of aloneness. But I found it to be more a mash-up between Thoreau’s “Walden” and an imperialism travelogue. Crusoe is easy to identify with at first as he shrugs off his parents’ expectations and yearns to sail the seas. He’s aware of the perils and admits “I know not what to call this, nor will I urge, that it is a secret over-ruling Decree that hurries us on to be the Instruments of our own Destruction, even tho’ it be before us, and that we rush upon it with our Eyes open.” Good reason is easily shaken off when we want to plunge headlong into life. Even after severe seasickness, near-ship wrecks and a two year bout of slavery he suffers through after being captured by Turkish Moors, Crusoe still longs to set out on a ship and ride the seas again. Having escaped from slavery, he tries to evade being captured again by sailing down the coast of Africa in a small boat. All the while he’s apprehensive of the wild animals and “natives” he fears might be cannibals on shore. When he does encounter some Africans they are welcoming and give him a number of supplies. His small escape boat is finally taken up by a Portuguese ship which carries him to Africa. The captain of the ship buys some of the goods he’s procured and assists him in setting up a tobacco plantation in Brazil. After setting up this promising enterprise he desires to set out to sea again.

This is where I really started to take issue with Crusoe as he decides to sail again because he wants to profit from the African slave trade. Having spent two years as a slave himself and experiencing the kindness of the Africans he encountered on their shorelines, did he learn nothing about common humanity? Crusoe himself admits that: “a certain Stupidity of Soul, without Desire of Good, or Conscience of Evil, had entirely overwhelm’d me, and I was all that the most hardened, unthinking, wicked Creature among our common Sailors, can be supposed to be, not having the least Sense, either of the Fear of God in Danger, or of Thankfulness in God in Deliverances.” However, his guilt isn’t over the enterprise he tries to embark on, but the fact that he still can’t settle down as per his father’s wishes. Therefore I could only feel a sense of satisfaction when his ship encounters a storm and he must painfully drag himself on the shores of a Caribbean island.

Goats playing peekaboo

The narrative of the story takes a strange turn here as he enumerates the way he gradually settles himself on the island building shelter from tools he salvages from his ship, eating goats and turtles he finds on the island and accidentally grows then actively cultivates barley and rice. Being on Kastellorizo really helped the novel come alive at this point since there are goats scattered all over the hills and turtles swimming in the bay. All this business in the novel of setting up shop alone on the island is good, but Defoe then strangely switches the narrative to a journal format within which he repeats almost everything about settling on the island that he already listed. It became somewhat repetitive.

Years pass by and gradually Crusoe takes on a more philosophical attitude. Instead of raging against the limitations of his situation he finds some contentment in the bare necessities he does have. This is when he really starts to sound Thoreau-like: “That all the good Things of this World, are no further good to us, than they are for our Use; and that whatever we may heap up indeed to give others, we enjoy just as much as we can use, and no more.” The narrative also slightly mirrors that of Walden as he becomes somewhat obsessed with enumerating his belongings and taking stock of what he has. As time goes on, he also acquires a very pious attitude as he unfortunately salvaged a bible from the ship which he takes to reading and ingesting. This wouldn’t necessarily be a problem, but, as can often happen, he takes ideas from the bible and develops a rather ‘holier than thou’ attitude while picking and choosing teaching that suit him while discarding others. I couldn’t help but wonder what would have happened if he didn’t have these “teachings” from the bible, but had to reason out and devise a system of principles about life all on his own.

The island is visited several times by cannibals who come with bound victims that they murder and then consume. Crusoe struggles with his conscience about what to do and whether to intervene. He’s repulsed and thinks to attack, but worries about being captured himself or invaded by many more cannibals. For a while, he has a sympathetic attitude towards them reasoning that they are merely getting their sustenance from human flesh in the same way he does from goats. Only when one of the intended victims begins to escape does Crusoe offer some assistance. He helps kill the cannibals pursuing the escapee and takes him back to his shelter. This man who is a cannibal himself is the famed character Friday. Being grateful for helping save him from his enemies Friday immediately pledges everlasting servitude to Crusoe – demonstrating this by laying his head upon the ground and placing Crusoe’s foot over it. At least, that’s how Crusoe interprets it.

Crusoe teaches Friday to speak English and about the Christian sense of God. They work together on the island for over thirty years, but all the while it’s very clear that Crusoe is the master and Friday the servant. Of course, I can’t help feeling uncomfortable about the assumptions about this relationship and the multi-layered colonial and racial implications of it. Crusoe was aided in his escape from slavery by a Portuguese captain but felt no desire to serve him. Yet, he assumes that he can turn Friday into a servant or Defoe naturally felt it was correct to write Friday as submissive to Crusoe without ever desiring his own freedom or a life apart from Crusoe. Defore writes Friday pathetically despairing at the idea of returning to his community or ever leaving his service to Crusoe. You could argue that their relationship on the island is symbiotic and they rely on each other. But what really troubles me about the tale is that for all Crusoe’s moralizing he never questions the injustice of slavery. Is this simply because it was a novel first published in 1719 when questioning such assumptions could not even be imagined? Like in Thomas More’s “Utopia” could a conception of paradise exist or society, even a society of two people on an island, thrive without there being slavery? The story is deeply problematic and becomes all the more uncomfortable because it feels like Friday never becomes a fully developed character in his own right.

In fact, towards the end of the story he is merely a comic figure. Once Crusoe is able to depart the island with Friday there is a very tedious account of Crusoe reaping large profits that he’s accrued from the plantation he left in Brazil and how he distributes this money to various people in a dreary number of pages like reading from an accountant’s record book. After this there is a bizarre and hurried story about his journey from Portugal to England and attempting to cross the Pyrenees in a snowstorm with ravenous wolves and bears chasing their party. Their guide is attacked by a wolf and bleeding on the ground. Friday takes this opportunity to play a prank on a bear passing by who he taunts and draws up into a tree. Climbing out on a branch the bear comes after him but Friday bounces so as to make the bear appear to “dance” as it attempts to cling to the branch. This makes all the men laugh and, presumably, it’s meant to be funny for the reader as well. But this is all we’re given about Friday’s life after the island since, of course, he wants to continue serving Crusoe without pay. Hilariously, amidst his quick post-island summary, Crusoe also recounts in two short sentences how he takes a wife who bears him three children and dies. Such a dismissive account seems apt for a novel which is so unconcerned with women. I read that Defoe wrote a sequel to “Robinson Crusoe” where the marriage is further developed but I really don’t feel compelled to seek it out.

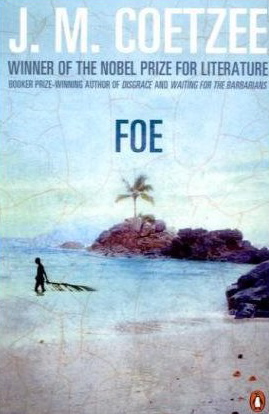

It might have been this aspect of the story that partially inspired JM Coetzee to write his novel “Foe” which is an alternative version to the Crusoe story, but from a woman’s perspective. I also read this while on staying on Kastellorizo. The novel is narrated by Susan, a woman who washes up on Crusoe’s island and lives for a time with Crusoe and Friday before they are all rescued. Crusoe dies on the journey back to England. Most of the book is about Susan’s attempts to get Daniel Defoe to write the story of their time on the island hoping it will become a big seller and help her escape poverty. There are many crucial differences between Susan’s story and the one which Defoe ultimately wrote and which we in the real world know. One being that Friday is physically mute because his tongue was cut out (by slavers or Crusoe himself we never actually know). Coetzee might be saying by this that Friday’s story is one which can’t be told and that his story is in fact much more interesting than Crusoe’s. He notes: “On the sorrows of Friday… a story entire of itself might be built; whereas from the indifference of Cruso there is little to be squeezed.” This and all the other differing details symbolize the difficulty of the existing text of “Robinson Crusoe” with its imperial ideas and problematic issues about slavery. It’s an interesting play on the original and Coetzee is a compelling writer to read, but my lasting impression of the short novel “Foe” is that it is more an intellectual exercise than an impactful story.

The last third of the book is mostly a debate about the nature of storytelling between Susan and Defoe. Some of this was very interesting as it explores where the self exists within the written work. I was particularly taken with how Defoe concedes: “In every story there is silence, some sight concealed, some word unspoken, I believe. Till we have spoken the unspoken we have not come to the heart of the story.” As if behind all the stories we tell there are underlying ideologies which aren’t spelled out specifically, but which we must try to define with language if we’re to be truthful to our ideas. Susan sees Defoe as the master of language she needs to tell her story in a way the public will find palatable. But Defoe wants Susan to tell her own story and they try and fail to get Friday to tell his in writing. It left me with quite a sombre feeling about the succession of knowledge by those who control the power over those who cannot impart their experience.

I read a couple of other island novels while away, but I’ll deal with those in separate blog posts if I can since this entry is already so long. Spending time on Kastellorizo gave me time for some inward quiet contemplation. The state of being on an island is that of taking on a circumscribed state of mind and becoming hyperaware of the isolated self. It is, of course, possible to feel very alone in a big city but you are constantly aware that you are amongst the great mechanical process of society. It’s so easy to defer one’s goals and excuse your own lack of accomplishments because of the impediments of being lost in the greater system of civilization. Whereas, being physically on an island all that exists is your own agency. In “Foe” Coetzee writes that “the danger of island life, the danger of which Cruso said never a word, was the danger of abiding sleep.” Alone on an island you know there is no expectation or need to do anything but meet your own basic needs. You can sleep your life away. Who would know? It’s interesting that sometimes we need the expectations of others or what we believe in our minds to be the expectations of other people to prompt us to industriously use our time. Maybe nobody will ever read this blog entry of mine. But would I bother writing this blog if I didn’t think there was the possibility it might be read? The potential that someone might come across our footprint in the sand (to steal a famous image from “Crusoe”) might be the only impetus a person can have to not drift into endless slumber.