When I saw the books listed for this year’s Dylan Thomas Prize one that I was most eager to read was Kirsty Logan’s new collection of stories “Things We Say in the Dark”. Logan is a writer who has produced a number of fictional books which creatively engage with traditions in horror writing and fairy tales to innovatively say something which is both current and personal. These new stories continue in this vein focusing specifically on themes to do with the home, family and birth. Many invoke imaginatively creepy imagery involving ghosts, haunted houses, witches, seances and animalism. Certain stories are dynamic retellings of folklore or classic stories such as ‘Hansel and Gretel’ or ‘Snow White’. In doing so, Logan gives an intriguing new perspective on gender, sexuality, relationships, parentage and violence against women and children. It’s deeply thoughtful how she engages with all these themes, but, most importantly, the collection as a whole revels in the deep pleasure of storytelling itself and how our nightmares function as a deeper form of self-communication. It celebrates the drive for riveting new kinds of tales which confront our worst fears as well as querying why these fears are an essential part of us.

The book functions as a series of self-contained stories, but there is also an overarching narrative where many stories are proceeded by an italicised account by a writer who is creating these tales in an isolated Icelandic location. While each story works just as well in isolation, I enjoy how this gives an added layer to the book for someone who reads them all sequentially. At first the author of these short reflective pieces seems to be Logan herself, but then it becomes clear it’s another creation and the dilemma of this (untrustworthy) fictional author is as eerie as the plight of many of the stories’ characters.

This adds to this collections’ overall propensity for creating stories within stories. Frequently characters are telling each other stories or telling stories to themselves of hidden pasts, powerful memories or fantastic dreams. And often personal obsessions or deepest darkest fears are revealed through how these stories are told and retold. At one point the “author” wonders at the philosophical meaning of all this: “We tell ourselves stories, we stoke our fears, we keep them burning. For what? What do we expect to find there inside?” Whatever catharsis or release is found from all this storytelling it’s clearly a trait of human nature and one the author wholeheartedly believes in as does the reader who boldly ventures to read on knowing some horror might be waiting.

Logan is careful to point out in the final story in this collection ‘Watch the Wall, My Darling, While the Gentlemen Go By’ that these tales aren’t merely flights of fancy but also deal with real world issues. This story’s narrator who is abducted and repeatedly raped thinks “Any minute now the story will be over, the credits will roll, he’ll say it was all a joke, run along home now. But the story isn’t over, because it isn’t a story”. Rather than being lost in the labyrinth of the imagination this is the stark reality of violence and it doesn’t symbolise anything; it’s the cruelty of misogyny and an abuse of power. Although she has a great reputation for reinventing fairy tales, Logan has an exceptional ability for portraying such difficult truths as she did so masterfully in her short story ‘Sleeping Beauty’ which appeared in Logan’s previous collection “The Rental Heart”.

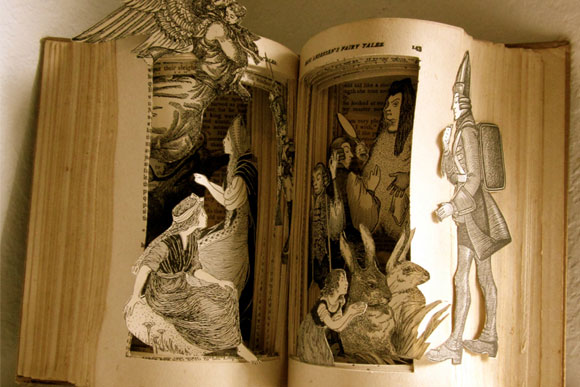

A cabin in Iceland

However, I also admire the sheer creativity, playfulness and lowkey sense of humour contained in many of these tales. Some of my favourites include ‘Stranger Blood is Sweeter’ about a female Fight Club, ‘Girls are Always Hungry When all the Men are Bite-Size’ about a sceptic who sinisterly seeks to prove that a psychic girl’s seances are a hoax, 'The Only Time I Think of You is All the Time' about the mysterious pull/compulsion of love and ‘The City is Full of Opportunities and Full of Dogs’ about a librarian whose self-consciousness about working in a building made of glass results in a disarmingly existential conclusion. Other stories are more conceptual in their form but no less emotionally impactful such as ‘The World’s More Full of Weeping Than You Can Understand’ which is a very short “nice” story which contains extensive footnotes detailing the terror which underlies simple descriptions or nouns. Also ‘Sleep Long, Sleep Tight, it is Best to Wake Up Late’ is written in the form of a questionnaire about sleep patterns and nightmares which raises disturbing uncertainties about the nature of reality and dreams.

All the tales in this excellent collection exhibit a wonderfully layered sense of storytelling. Often what seems disorientating or simply bizarre at first takes on more meaning and resonance as the story continues. While some stories may be too brief to create a truly lasting impact most give enough of a glimpse through the keyhole to reveal multiple dimensions and form a wider picture within the reader’s imagination. This takes a great deal of craft and talent. I thoroughly enjoyed losing myself in the darkness these stories unleash and discovering what Logan chooses to illuminate.