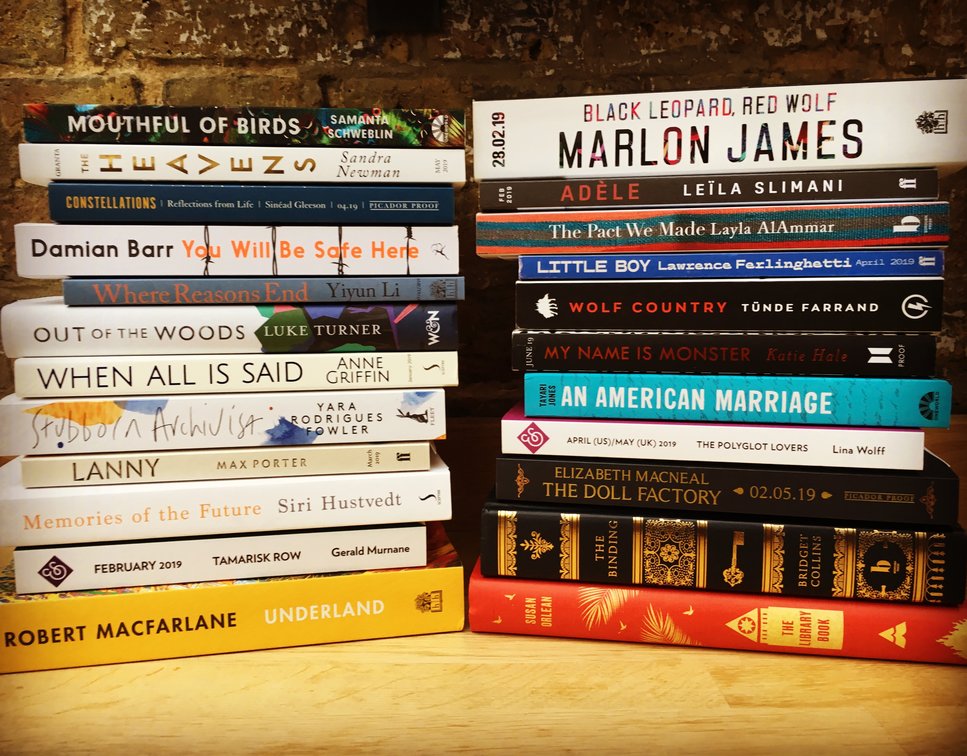

Some books leave me with little to say except I loved the experience of reading them. Maybe I should leave it at that in regards to this particular novel. But it's funny because Anne Griffin's debut novel “When All is Said” is a story that's so dominated by story itself it doesn't invite the reader to do anything but listen in rapt delight. It's told from the perspective of 84 year-old Irish farmer and businessman Maurice who sits in a bar having several drinks to honour people who've had a significant impact upon his life. And the experience of reading this book is like that feeling of listening to an old man brimming with tales to tell: some wickedly funny, some heart-wrenchingly sad and some that come with twists so disarming they left me stunned. So by the end of the book I was left feeling like this man's life had washed over me. I was moved by all his disappointments, passions and sorrows. There's also a blissful sense of release because Maurice is someone who always had difficulty expressing his feelings throughout his life and found it challenging to communicate as he suffered from a learning disability. Like the inverse of a series of reminiscences at a funeral, his narrative at this very late stage in his life is the most beautiful tribute to the people who made him who he is and a profound kind of letting go.

Naturally, because Maurice has lived so long, he has observed many physical and social changes to his country. Like in John Boyne's “The Heart's Invisible Furies”, part of what's so mesmerising about this man's story is to realize how much things can change in the course of a lifetime. It's shocking now to read how several decades ago a very young man like Maurice who comes from a desperately poor family could go to work on an estate and receive such horrific verbal and physical abuse from the lords of the manor. And this shows so poignantly how feelings of hurt and a desire for revenge can come to dominate a man's life. Maurice also describes why he's had such trouble emotionally opening up and being forthright about what he wants in life: “People didn’t really do that back then, encourage and support. You were threatened into being who you were supposed to be.” For a new generation that's raised with gentle words of encouragement and a sense that you should become the person you're supposed to be, it's quite sobering to realise how difficult it'd be to grow up under such strict tutelage.

Part of the immense pleasure I found in this novel is in it's all-encompassing Irish-ness. And no man is more Irish than Maurice: a straight talking self-made man of the Earth, loyal to his wife, likes a good drink and tells a spellbinding tale. His sensibility mixes humour with sorrow, humility with the grandiloquent and irony with the utmost sincerity. These dualities make his tales so bewitching and pleasurable to read. Perhaps he sums up his own feelings for the people closest to him best when describing the relationship that existed between his wife and her mother: “There was a love but of the Irish kind, reserved and embarrassed by its own humanity.” But here in this novel he finally divulges his experiences and unvoiced feelings to commemorate all the details of his fascinating life.