When discussing the shortlist for this year’s prize I described how difficult it was to call who might win and I was surprised to see “Milkman” triumph last night. But I think this is a fantastic result for a number of reasons despite my heart’s wish to see “Washington Black” win and my finding Anna Burns’ novel a bit of a slog to read overall.

Many people will now buy “Milkman”, but I think the reality is that not many people will finish reading it. This goes to the centre of a longstanding tension between what you could term readability vs literary quality. Often we’re made to feel that challenging books are something we should force ourselves to read because they are “good” for us. Not many people would describe “Ulysses” or “Moby Dick” as delightful reading, but they’ve had an undeniable cultural influence and, of course, you can still find great pleasure in reading them. Many times challenging yourself to better understand a complex text can yield a lot of joy. My point is that I don’t think readability and literary quality are mutually exclusive. Also, we’re often made to feel if we don’t “get” a book we’re somehow less of a reader. If you’re not enjoying something don’t force yourself to read it. It simply might not be a book for you. Our relationships with individual books is complex. Sometimes it might be a question of timing or the circumstances in which you’re reading it. In this case, despite my reservations while reading “Milkman” I kept reading it not because I felt I had to, but because there were such insightful gems and moments of brilliance I wanted to see how the novel played out. I’m certainly glad I stuck with it because I really connected with the dilemma and justified indignation of its narrator, but if you gave up on it or start reading it now and decide to give up on it that’s a totally valid decision. And maybe you’ll want to try it again some day.

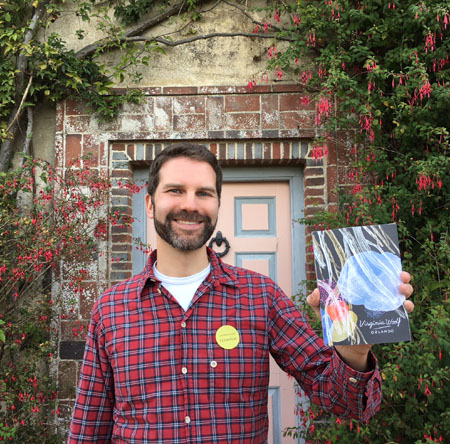

Here’s a special edition of the novel which the prize designed just for the author.

It also feels like “Milkman” being selected as the winner was something of a political choice. As has been often noted, a female author hasn’t won the prize since Eleanor Catton took the trophy in 2013. That Anna Burns is also from Northern Ireland feels significant as well – especially in the midst of Brexit. It’s great that the novel winning this award will bring more of a focus to female voices from this part of the world. If you’re interested in discovering more writers from Northern Ireland I’d highly suggest reading the anthology “The Glass Shore” which includes a wide range of short stories from many talented female writers from the North of Ireland. The fact that Burns’ gender or country of origin might have played a factor in the judges’ decision shouldn’t detract from the individual literary quality of “Milkman”. It’s a singular achievement (as all the novels on the shortlist are) so it just adds another dimension to the joy of this book winning.

I was lucky enough to be invited along to some of the parties last night so I also made a video discussing the shortlist a bit more and filming a vlog of my experiences on the night which you can watch here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a5X1vVokxfo&t=200s

Let me know what you think of “Milkman” winning the prize this year? Have you read it or are you tempted to read it now?