I've been reading about Persephone Books for a long time. This is a publisher who (in their own words) “prints mainly neglected fiction and non-fiction by women, for women and about women.” Of course, I love books by women and think it's brilliant a publisher with this mission exists, but part of me still feels slightly transgressive stepping into this female domain. It's like when I was growing up in the US I often watched the TV channel Lifetime whose motto came up at every commercial break: 'Lifetime... television for women.' And I'd think guiltily 'Oh, this isn't meant for me' or 'what kind of man am I watching so much “women's” television?' But, who cares, right?

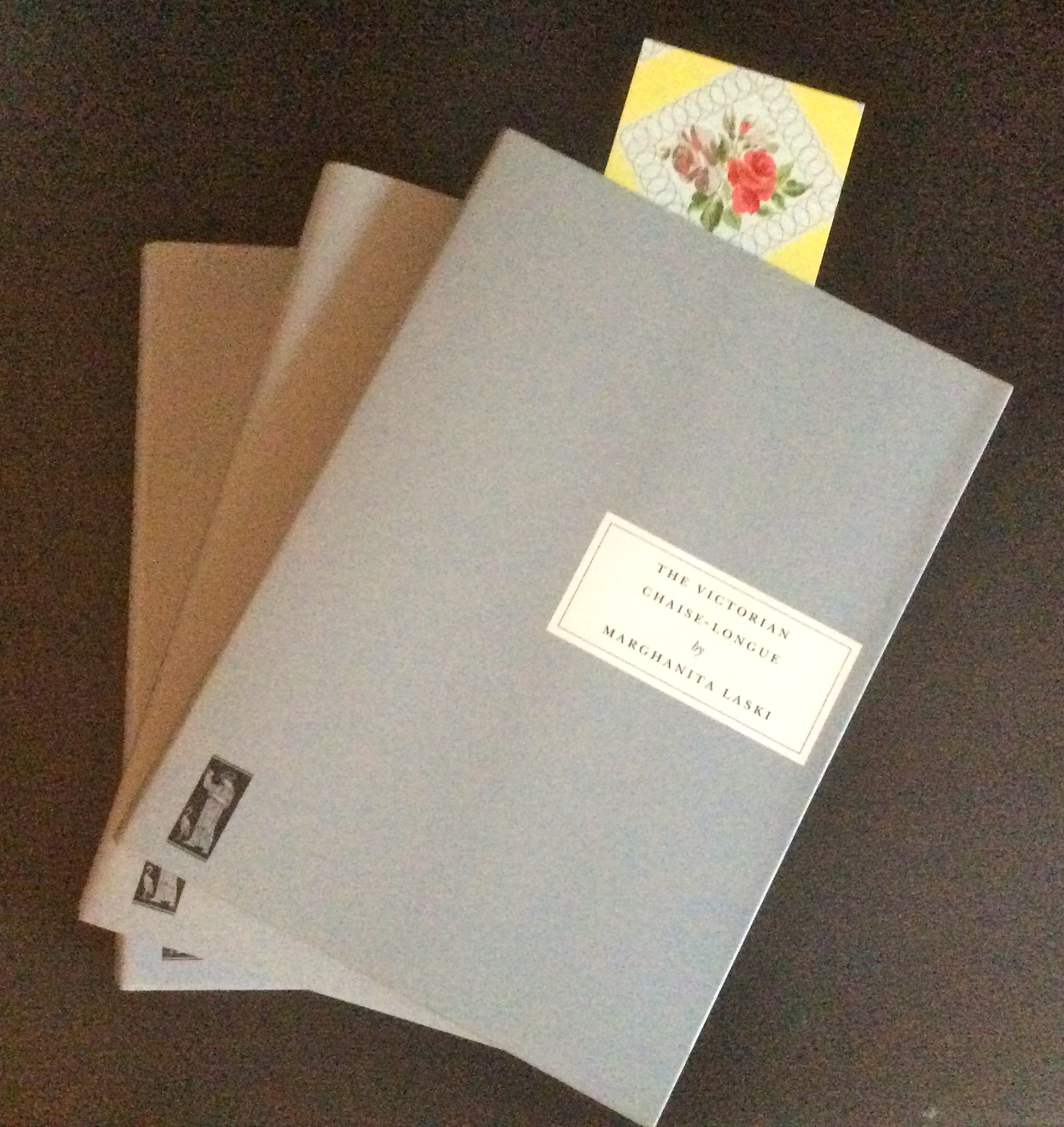

So I finally went to Persephone's shop in London on Lamb's Conduit Street which is only a 15 minute walk from where I work on weekdays. It's a beautiful outlet brimming with dove-grey covered books and tasteful furniture. I couldn't resist buying a few titles and one that caught my eye in particular was this short novel “The Victorian Chaise-Longue” by Marghanita Laski which was first published in 1953. Part of the initial appeal is that I love a chaise-longue and after reading what the novel is all about I was very curious to have a read. It tells the story of Melanie, a young mother who is recovering from tuberculosis. Since she's recovering she's allowed to move out of bed onto a chaise-longue in another room that has a view. Melanie is rather spoiled. She acts like a passive, “girlish” female and is treated like such by her husband and doctor. Cooing like a baby to the men around her, she seems rather glad to remain in her vegetative state with her own baby being entirely cared for by the nanny. She drifts off to sleep and awakens on the same piece of furniture many years earlier in Victorian times as a different but similarly named (Milly) woman. Milly is also an invalid suffering from consumption. Strangely, the consciousness of the women has blended so Melanie is aware of certain facts about Milly's life and can't verbally articulate the knowledge she's brought from the future. Here she is watched over and protected by Milly's sister and a doctor who is smitten by her. Melanie desperately tries to find a way to escape this condition and return to her own century and body. She thinks there must be a specific task she needs to accomplish for Milly and that she must uncover a pattern to liberate her from this body swap situation. The concept is like a blend of the television show 'Quantum Leap' and the movie 'The Matrix'. It's a brilliantly original and dark tale to have been first published in the early 50s.

Part of what Laski was trying to get at is the forbidden pleasure women can deny themselves or feel like they can't discuss. Melanie is haunted by a fuzzy memory of being pressed into the chaise longue by a man. Gradually, Melanie discovers that Milly has a taboo secret which has been kept from her sister. But this forbidden pleasure isn't just the erotic. Melanie observes: “I was in ecstasy as I fell asleep, ecstasy one experiences perhaps once, twice, half a dozen times, when to be human is no longer a lonely terror but a glory, when time is blotted out by perfection.” This notion of “ecstasy” is brought up over and over throughout the book. It's something wrapped up with the forbidden and slowly the concept turns into one more as a prelude to terror than blissful release.

Marghanita Laski was herself obviously a very intelligent and capable woman. So, in writing about a female character who is initially so simpering and passive, I think she must have been making a statement about the responsibility women owe to themselves not to defer to masculine/paternal attention to bolster their own self worth. Melanie experiences the full horror of what it is to be trapped in an era where if a woman clandestinely expressed her desires and was found out, she would be stigmatized and punished (as it becomes partly clear that Milly has been). In Melanie's own time of 1950s Britain there was still a lot of sexism obviously, but there were more opportunities for women to forge forward with a more enlightened social consciousness. It's stated at one point that “sin changes, you know, like fashion.” This notion of a shifting moral landscape hints that actions so badly stigmatized at one point of history won't necessarily be in another. We have a duty to assist humanity in it's progression. To lazily harken back to conservative social rules that inhibit people from becoming fully realized human beings is akin to death.

I love the way Laski plays so confidently with time in the narrative, taking the reader on such a fantastical journey in so few pages. This takes daring and it's to the book's credit that it chooses not to entangle itself too much in the hows and whys this occurred. Melanie is obviously mystified by what's happened to her and the narrative closely follows her perspective, but clearly Laski is reaching more for an artfully articulated social message than a sci-fi adventure here. The book (and Melanie) become compellingly philosophical as the story progresses. She observes: “Time may be going not in a straight line but in all directions and in no direction, and God may have changed the universe so that it is my body that lies here and no dream, or not my body and still a dream from which I shall be freed.” The story becomes somewhat Shakespearian in the interplay of high drama mixed with observations about the human condition. But brilliantly, even as the intellectual fervour of the novel amps up, so does the tension in the story. Melanie's desperation to escape being trapped in this other woman becomes frighteningly intense. The final pages are utterly gripping.